Sponsored By: Deel

You found global talent. Deel’s here to help you onboard them.

Deel has simplified a whole planet’s worth of information. It’s time you got your hands on our international compliance handbook, where you’ll learn about:

- Attracting global talent

- Labor laws to consider when hiring

- Processing international payroll on time

- Staying compliant with employment and tax laws abroad

With 150+ countries right at your fingertips, growing your team with Deel is easier than ever.

I’m a writer, and I think writing is hard. The first time I (glorified wordsmith) saw a bunch of algorithms (AI) output writing (aka do a hard thing), I took a beat. A mixture of surprise, fear, and curiosity washed over me. This was the end of 2022 when OpenAI released ChatGPT.

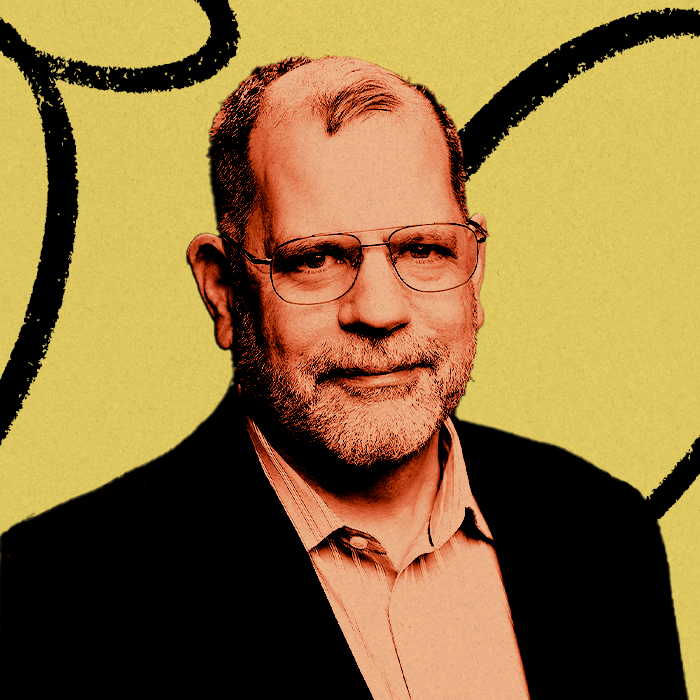

Tyler Cowen felt some variation of this decades ago, when he saw a bunch of algorithms (AI, again) directing chess pieces across a board.

Cowen is not a professional chess player. He’s an economist who just happens to be a chess enthusiast. But when news broke that AI had mastered chess, a game often hailed as the pinnacle of human intelligence, Cowen sensed that something important had occurred. He concluded that the next technological leap would be in AI. Armed with a deep knowledge of economics, he explored his insights further. In 2013, when the rest of the world was Instagramming their lunch, Cowen published Average Is Over, a book about how AI would change the future of work. In it, he argued that the economy will shift to reward those who can enhance the capabilities of technology.

Cowen had his AI moment a decade ago. Today, his incredible foresight is more than words and theories—it’s our reality.

During the day, Cowen teaches economics at George Mason University. He moonlights as a prolific writer, co-writing leading economics blog Marginal Revolution, where he has published daily for over 20 years. He is also the author of 17 books, the latest of which is an AI-fueled interactive experience that analyzes the lives of influential economists and crowns one of them as the greatest of all time.

Dan interviewed Tyler Cowen to understand how Cowen uses AI in his own life and work—and what that might mean for the future of jobs and the economy. These are edited excerpts of the interview. Let’s dive in.

Tyler Cowen introduces himself

I am Tyler Cowen, and I’m an economist, professor, and writer.

I am fascinated by the future. I’m driven by a hunger for discovering what lies beyond the curve. I articulate my findings in books, articles, and on my blog, Marginal Revolution.

Lately, I’ve also been sharing my thoughts more through public appearances. This is a conscious decision, fueled in part by the burgeoning AI revolution. As AI grows more powerful, I believe there will be a restored emphasis on intrinsically human qualities like charisma.

Am I charismatic enough? That’s for the world to decide. Or perhaps, if I look far out into the future, it will be for AI to decide.

I think we will eventually be able to use AI to evaluate people’s talents. It will be highly meritocratic in a narrow way. I'm not sure we'll all be happy with it. It can be unsettling to be told just how good you are at something. On net, it can diminish human happiness. But it will also enable us to find potentially successful people easily.

My deep-rooted optimism about AI and its capabilities is rooted in chess. I’ve always liked a good game of chess. For many years, the popular conclusion was that AI could not play chess. It was too conceptual, too complex, too non-legible. That didn’t last for too long. Now, AI is almost godlike when it plays chess.

When I realized that AI could play chess—a really hard thing, in my book—I was convinced that it could learn how to do a lot of other things in time.

My obsession with the future kicked in. I wanted to be ahead of the trend and write about where I thought it was going. So I wrote a book about how technology would change the future of work.

With the advent of consumer AI, I have the privilege of seeing my careful predictions be tested against reality.

Predicting the short- and long-term effects of AI

I don’t think we know yet which groups of people AI will help and harm the most. We’re still waiting. I expect many surprises.

However, I’m still willing to hazard a guess about the effects of AI. In the short term, my best guess is that AI will be an equalizer of sorts. People who can’t do things at all will soon be able to do them pretty capably, like writing an online essay to get into college. The smartest kids could already do that. ChatGPT won’t help them much. But it sure will work wonders for others who struggle with essays.

However, I suspect that the long-term effects of AI will be far less egalitarian. Talented people brimming with ideas will derive higher benefits than the rest of society. As we learn how to use AI better, these people will leverage it to build out projects. They'll have better record keepers, translators, mathematicians, coaches, colleagues, advice givers…you get my drift. Of course, you can use large language models to help you find ideas, but they can’t go out and do it themselves. So I think the economy will adapt to rewarding some kind of hyped-up executive function.

I believe AI is excellent at managing people. Those who learn how to leverage it will be hugely productive. Companies might shrink in size, while still remaining rather potent. We’re already seeing this play out—take Midjourney. When it had its breakthrough, it had seven or eight people working there. However, an underappreciated risk of this is that AI might help poorly run terrorist organizations manage themselves better, increasing their chances of causing greater harm.

One thing that has surprised me about the current generation of AI models is their facility with words and emotions. I’ve always assumed that intelligent machines would take the form of some sort of autonomous reasoning tool. But ChatGPT is incredibly facile at taking an idea and writing a rap song about it, or a poem, or a shanty song, or whatever you might want. Large language models are also wonderful therapists that can be incredibly objective when that’s what you ask them for.

AI can help humans understand themselves more deeply. I’m about to turn 62, so that’s of relatively less value to me, but I have been using ChatGPT for a variety of tasks, both personal and professional.

Using ChatGPT while traveling

I love traveling and I’ve found that ChatGPT is the perfect companion, especially the ChatGPT app on my iPhone. When I’m in a foreign country, it forms a bridge of sorts, allowing me to meaningfully connect with my environment.

Let me give you an example. I was in Tokyo recently, I don’t speak Japanese, and not many people there speak English. But I used ChatGPT as my translator to effectively communicate with the world around me.

I also like sampling different kinds of food. I remember I was at a Paraguayan restaurant in Buenos Aires and wanted to eat something authentic. I’d never been to Paraguay and had no idea what that would look like. I just took a photo of the menu and asked ChatGPT: “What should I order here? Which are the classic dishes?” It just told me and I think that’s amazing.

ChatGPT is also a vehicle to fulfill my curiosities. I was in Honduras some time ago and when I saw something I wanted to know more about, I just sent a photo to ChatGPT. If you see a plant or a bird you don’t know, you can take a photo and send it to ChatGPT and ask it: “What’s this?” And it will tell you. This is objectively good because you learn new things. It’s also easier and quicker to use than Google and Wikipedia.

Using specific prompts to do deep research

I use ChatGPT to learn obscure pockets of history. I’ve found that it happens to be far more intelligent there than in many other domains.

I used ChatGPT to interview the 18th-century Irish writer Jonathan Swift on my podcast. I asked GPT Swift a series of detailed, probing questions for an hour. It didn’t make any mistakes. Not one. What you see online is the very first try. There were no redos or no trial runs. Presumably, ChatGPT has read a lot of Swift and read a fair bit about Swift. The interview I conducted was weird and detailed enough to point ChatGPT to the smart corners of the internet. That’s why I worry about hallucinations a lot less than most LLM users. ChatGPT just has a low tendency of hallucinating in the areas where I typically use AI.

Now, I know the kind of question that would probably make ChatGPT hallucinate. Ask it something like: “What are the three best books to read on Jonathan Swift?” My best guess is that one of three answers it comes up with won’t exist. This is likely because the prompt is too vague. But I don’t run into it so often because I’m not asking ChatGPT these questions.

Let’s say I do want to ask ChatGPT a general question, maybe about the meaning of inflation. I wouldn’t just ask: “What is inflation?” The answer it would give me probably wouldn’t be much better than Wikipedia. I might ask: “What is inflation? Answer as would Milton Friedman.” That will pretty much always get you a better answer. This helps point ChatGPT towards smarter bits in the matrices. The stuff it knows connected with Milton Friedman is smarter than the stuff not connected to Friedman.

For obvious reasons, I don’t find myself asking ChatGPT basic questions about economics. I’ve been using it to find out more about the insurance industry, which I don’t know nearly as much about.

Finding the best data by asking for comparisons

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!