If you spend enough time in venture, you begin to see the same idea come up time and time again. Generally, these are “tar pit” ideas: they seem compelling at the surface, but underneath lies a well of corpses from attempts in the past. Think marketplaces for monogamous demand—wherein you want the same provider each time, as with nannies and cleaning services—discovery apps, etc.

Another classic of Silicon Valley: a stock market for people.

Theoretically, the idea makes sense. If you have people you believe in, buying “shares” in their life and getting an upside when they make it is rational enough. This works for companies, so why wouldn’t it work for people?

There have been a few recent attempts to do just this, using income sharing agreements (ISAs) and efforts like Bitclout, which was a similar bid to create a stock market around individuals via the blockchain.

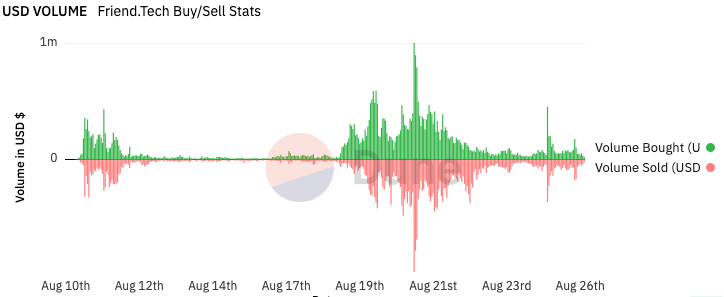

The latest iteration is friend.tech, a crypto project that lets you buy “keys” based on the strength of an individual's influence. Predictably (greed gonna greed), trading went viral on X, and volume soared. Mostly, the people being bought were influencers within the crypto community. Within a few days, interest died down.

The issues with the “personal stock market” idea are, unfortunately for founders, foundational.

The first issue is to look at when such ideas have existed in the past, notably slavery and indentured servitude. Both structures flourished while they were legal, as the law was on the side of capital. Now, rightfully so, both are illegal, and the law protects labor. This highlights a fundamental problem for capital—the law now favors individuals (for example, you can eliminate most debt and financial obligations by declaring bankruptcy). Speculation on market fluctuations may still have demand, but underlying assets (like cashflow and labor) are off limits from an enforcement perspective, hollowing out the value proposition for “investing in individuals” and leaving speculation as the only utility.

So stripping down the “stock market for people” value proposition to “gambling on assets loosely associated with individuals with no underlying economic component” then begs the question: is speculation enough?

In order to flesh out the answer, it’s important to distill the idea in question to its core components, something I call the “atomic value swap.”

This is a framework by which you can evaluate why users of your platform engage with it. By utilizing the tools of economics and behavioral psychology, atomic value swaps let you understand why people use your product. It strips everything down to the base level—the more confidently you can answer the question of why users engage with your core product loop, the better you’ll be able to build around it.

Products like friend.tech tend to struggle in the long run because there is a misunderstanding about what type of value swap users are engaging with.

The sacred and the secular

The simplest example of an atomic value swap is paying for a good or service. You want something done, you give someone cash to do it. For example, it’s hot outside, so you go to a bodega and buy a bottle of water. Both parties deem the transaction to be beneficial, and therefore the transaction occurs. If the price is too high, demand will not engage in the transaction. If the price is too low, supply will not engage in the transaction. This kind of measurable, quantifiable value is called “secular.”

However, a lot of value and utility is not secular: love, spirituality, parenthood, friendship, family. How do you put a price on the value of religion to the devout? How do you value a best friend? It’s not possible.

Now, before the cynic exclaims, “Everyone has a price!,” what we are looking for is not whether a price exists, but if there is a price consensus. Therein lies the distinction—“sacred” values describe value or utility where every person has their own highly varied ascribed value and there is no market clearing price. The micro and the macro are not aligned. The only letter you have from your grandparent? Priceless to you, worthless to someone else.

This contrast of sacred and secular is key to understanding why things go wrong for so many startups.

Secular-to-sacred atomic value swaps—in which the sacred is uniquely priced to the individual—are significantly more complicated to understand and nearly impossible to scale. Behavioral psychology tends to skew expected reactions from supply or demand to changes in the transaction.

Imagine this: your friends with a toddler want to go out to dinner and ask if you can babysit. Great! They’re good friends and deserve the time to themselves, and you love their kid—you agree. Now, they offer you $30 to do it. All of a sudden it feels off—but why? You were happy to be a good friend even before the notion of money entered the equation. By introducing a quantitative value, it forces you to put a price on your time and makes the nature of the exchange more transactional. Further, they’re assuming that you actually want to be paid. Maybe at the end of it all, you suggest that it’d be better if they found a regular babysitter.

More often than not, introducing a secular component to a previously sacred exchange perverts the transaction in unintended ways. Consider a field study by economists Uri Gneezy and Aldo Rustichini in 2000. Daycare centers were trying to get parents to pick their children up on time since late pickups forced teachers to stay late. To combat this, they introduced a fine of $5 if parents were more than 10 minutes late. Theoretically, this economic penalty ought to act as a deterrent and mitigate the unwanted behavior. Perhaps surprisingly, the result was the exact opposite. After the fine was introduced, late pickups increased dramatically and stayed that way even after the fine was removed several months later. By introducing a fine, the daycare centers unintentionally put a price on parents’ time—one that many were happy to pay. In fact, if any parent valued their own time at more than $30 per hour, they technically ought to show up late every single day.

The important thing about the important thing

The tricky thing is that successful companies have been built around all three types of value swaps.

Secular-to-secular swaps create marketplaces like Airbnb and Amazon. Money is exchanged for goods and services.

Secular-to-sacred swaps are most prominent via self-expression—everything from cosmetics in Fortnite to luxury goods from LVMH. Money is exchanged for subjective levels of social signaling.

Sacred-to-sacred swaps describe most interactions on social media: viewing someone’s story, liking or commenting on a post, sharing a funny video. Subjectively valued effort or time spent is exchanged for subjective social signaling and validation.

What matters is being clear-eyed about the kind of swap you’re building for. To understand the swap your product is built around, as well as the durability of the swap, I ask myself these questions:

- What is the value being delivered?

- What is the perceived value of what is delivered?

- Is the perceived value objectively uniform or subjectively irregular?

- How fairly compensated is the value creator for value delivered?

- Is the compensation objectively uniform (money) or subjectively irregular?

Friend.tech and all future “stock markets for people” will struggle because the secular-to-secular value swap is out of favor from a regulatory perspective and will not work at scale. To fill the void of legal protection, the company’s solution is to add the sacred value of social pressure as a substitute for regulatory enforcement. But while it may be a viral marketing hook, the cost is more than it’s worth in the long run.

In order for someone to participate, they need to subject themselves to being priced, which will always be too low or too high. The price will never be accurate in the subjective view from the individual being valued, and the dissonance will push the user away via insecurity and fear of rejection. Without the active participation of a subject on the platform, the underlying security has no recourse value, and the value of the “asset” goes to zero.

The exercise of boiling an idea, product, or company down to a fundamental level is critical to understanding its potential, viability, and longevity. Complexity can mask instability. The only way to see the true nature of something is to distill it down to its simplest form—its atomic value swap.

Chris Paik is an investor at Pace Capital, an early-stage venture capital firm based in New York City with $400 million under management. Prior to Pace, he was a partner at Thrive Capital, where he led the investments in and served on the boards of Twitch, Patreon, and Unity.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

This could have been expanded and led out with more examples. Secular to Secular isn't out of favor from a regulatory perspective, it's only out of fashion when you want to trade labor in this particular fashion. There's no regulatory damper on paying people in a secular to secular swap of labor for money.