(all $ is USD unless noted otherwise; CAD figures are converted to USD at $1 USD: $1.28 CAD)

The waste management business isn’t hard to understand conceptually, though to get a felt sense of the territory probably requires a bunch of ground level inside knowledge because the competitive dynamics differ so much by market. Still, the publicly traded US and Canadian majors (WM, Republic, WCN, increasingly GFL) are the byproduct of literally thousands of small collection and landfill outfits rolled up over decades, with many of those entities roll-ups themselves…so, from an investment perspective, I think you can average over a lot of the nuances and arrive at a usable coarse-grained assessment, which is what I hope to provide here.

If asked to think of a business that I am near certain will still be around 50 years from now, waste management would be on that list. You don’t have to worry about this industry ever being obsoleted away. We’ll always need companies to collect our trash and dispose of it safely.

Volumes are economically sensitive but profitable and resilient. In 2009, their worst year in at least 2 decades, Waste Management and Republic still managed to produce ~25%-30% EBITDA margins on volume/price declines of -8%/-4% and -10%/-1%, respectively. During the peak COVID quarter of 2q20, their margins were barely dented on 7% and 10% organic revenue contraction. Over the last 2 years, pricing contributed ~4% to GFL’s organic growth, volumes another ~0.5%-1%. From 2013 to 2019, Republic’s core pricing/volume averaged 4%/1% and WCN’s averaged 3%/1%. So 4%-5% organic growth (excluding fuel surcharges and FX) seems about what we should expect for the vertically integrated public majors over time, and with some operating leverage maybe that translates into ~6%-7% organic EBITDA growth.

Waste management has two parts to it: collection and disposal. On the collection side, men drive around neighborhoods in trucks picking up trash and transport that trash to a nearby transfer facility or landfill. It addresses two types of customers:

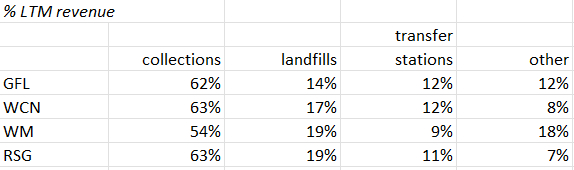

- Residential: these are served under 3 to 10 year exclusive (”franchise”) contracts struck with municipalities. Typically, the operator is paid a fixed amount per home per month, with pricing indexed to CPI plus fuel surcharges. A hauler’s labor costs will typically inflate faster than CPI so it’s common to see margins compress over the term of contract. Route density matters but it’s not an advantage since whoever wins the municipal contract collects trash for all the homes in a neighborhood.

- Commercial and industrial: commercial includes retailers, restaurants, offices, etc.; industrial refers to automotive, manufacturing, construction, and the like. Contracts are typically 1-5 years in duration, with flat monthly fees pegged to the number of pick-ups. Unlike residential, commercial contracts are generally negotiated with end customers rather than with municipalities. They tend to have more flexible and generous pricing terms, with price escalators outpacing CPI, as waste pick-up and disposal is a low cost item for most businesses, who will often absorb double-digit price hikes every year without too much push back.

Residential volumes carry the lowest EBITDA margins, somewhere between 20% and 25%, but they are very sticky and secured under long-term contracts. Commercial volumes have much higher margins, somewhere between 30% and 40%, but also churn at ~9%-10% vs. maybe low-single digits in residential. Industrial is like Commercial as far as contracts go but are more cyclical and lower margin.

In some markets, residential and commercial volumes are tied to a single exclusive contract awarded by the municipality or county. For instance, WCN gets ~40% of its revenue from franchise markets in Western states, where they have a monopoly on all residential and commercial waste pickup under 10 to 25 year contracts under which they pay a 5% royalty revenue to the jurisdiction, with pricing pegged to local CPI. Republic has a similar arrangement in Las Vegas. Barring a major screw-up, these contracts never come up for renewal. The only way to break into these markets is through acquisition.

In both resi and commercial, consistent service is the most important consideration when choosing a trash collector. City officials don’t want to field missed pickup complaints from angry voters and local restaurants don’t want fumes from piling trash heaps greeting customers in the parking lot. But there aren’t many ways to differentiate on this vector. So long as a hauler shows up on time and doesn’t leak garbage juice everywhere, volumes stay put. Businesses aren’t trying to squeeze every last bit of savings from a negligibly small cost item and municipalities really don’t want to re-bid contracts, a process that can take up to a year and disrupt service for thousands of residents. Hence, Waste Management and Republic retain more than 95% of their customers every year.

Trash collection is a fragmented, commodity business with low entry barriers. On the commercial side, it helps to have route density (the more businesses you have along a route, the more cost effectively you can serve an incremental customer), but otherwise profitability is a function of disposal fees paid to landfill operators, fuel efficiency, and operational excellence, which latter includes things like driver productivity, turnover, and safety. Winning exclusive residential contracts doesn’t yield many operational or density benefits on commercial since the trucks that pick up commercial roll-off dumpsters and compacters are completely different from those that curbside collect residential trash containers.

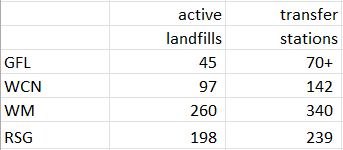

Disposal operations are harder to replicate. Landfills can take up to a decade to develop. There are all sorts of permits and zoning approvals required to design and construct a landfill, and absolutely no one wants to live near one. In the US, their number has declined from 10,000 in the late 1980s to around 2,000 today, with most owned or operated by 5 companies who have the resources and processes to safely manage them. To limit travel costs in cases where landfills are distant from collection points, haulers will dump their loads at transfer stations, intermediate disposal facilities where local trash is collected and compacted before being transported, by rail or collection truck, to a landfill. [Note: Landfills and transfer stations are operated by both municipalities and private enterprises. Private enterprises charge volume or weight-based fees to haulers who unload at their landfills, which they lease or own or even operate on behalf of municipalities.]

Transfer stations are treated as extensions of landfills and generate no-margin pass-through revenue. Landfills generate EBITDA margins roughly equivalent to or sometimes higher than commercial collection (varies by operator), somewhere between 40% and 50%, with incremental margins running 60%-70%. Some will say that landfills are where the real money is made, but it’s important to recognize that they are capital intensive to run so the returns are pretty mediocre. WM, for instance, recorded $18bn of investments in their landfills, by far the largest component of their gross PP&E. Management tells me that margins here are between 30%-40%, so even at the high-end of that range WM’s landfills are returning just under 10% pre-tax. Still, landfills have spillover benefits: 1) disposal fees are often the largest cost after labor, accounting for 20%-25% of collection revenue, so internalizing volumes supports collection margins and 2) they can instill price discipline since a local independent hauler must charge enough to at least cover disposal fees.

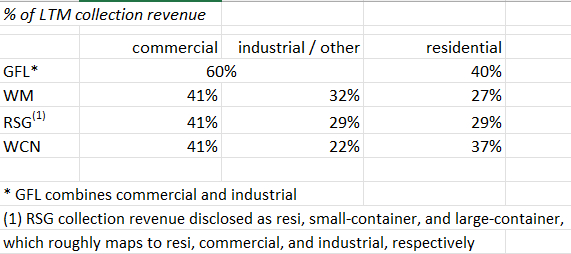

Here’s how revenue is split across the 4 publicly traded majors:

So with Collections delivering ~20%-30% EBITDA margins and landfills doing 30%-50%, consolidated margins blend to a consolidated ~27%-30% across the big 4.

Those profitability ranges are rather broad because returns can vary a great deal by market, with commercial haulers in some cases earning twice twice as much per yard in secondary locations as in competitive urban locations.

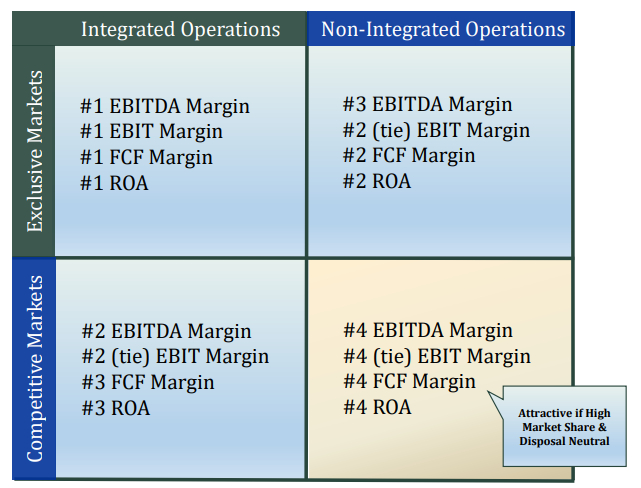

Source: WCN

WCN produces 3 to 5 points more margin (30%-31% vs. 25%-28%) and better customer retention than WM and Republic. It believes that 3/4 of this performance gap comes from market selection (the remaining 1/4 from superior execution).

The majors have a few other ancillary lines of business. They convert methane gas oozing off their landfills into renewable natural gas (RNG) that can be pipelined away and used in natural gas powered vehicles and industrial applications. They all pick up, sort, and sell recycled materials to intermediate processors who transform our plastic bottles into resin that gets sold into Coke and Pepsi bottlers or whatever. Something you often hear is that since China stopped taking our plastic and cardboard, prices for recycled commodities have swooned, turning recycling into a crappy business that is operated primarily as part of a bundle to win municipal solid waste contracts. But apparently now it is common to charge fees that allow for a bare minimum return on invested capital while splitting excess profits from rising commodity prices with customers. WM tells me that at mid-teens ROIC, recycling is the highest return business after commercial collections.

Of the big 4, WM and Republic are more or less in stable end states, too big for needle-moving M&A. To re-cast itself as a sustainability company, Waste Management changed its name to “WM” and began pushing ESG initiatives, telling large national accounts how much of their waste is being landfilled vs. recycled. They also remove hazardous waste for households and have the scale to invest in apps and safety technology. As the largest waste company in the industry, WM does this to show they are being good corporate citizens but I doubt it meaningfully alters the return profile for investors. For WM and Republic, the basic algorithm is to grow EBITDA high-single digits, retire 1%-2% of the share count every year, and grow per share free cash flow 10%-13% over time. They take pride in paying consistent dividends. Great. Nothing wrong with that.

But if you’re an active investor looking at waste management, I’m going to bet that you’re interested in either WCN or GFL. WCN is a mature entity but has a counter-positioning angle to its narrative. Compared to the top-down centralized approach of WM and Republic, WCN runs decentralized, granting district managers, whose compensation is tied to contract profitability and is far more heavily tilted to equity than their counterparts at WM and Republic, the authority to make hiring, pricing, compensation, and capital allocation decisions. Whereas WM and Republic operate in competitive urban locations, WCN limits itself to secondary markets, where it enjoys a literal monopoly in many cases. And while WM and Republic run a traditional top-down chain of command, WCN fosters a “servant leadership” culture, which basically means that managers assume a humble attitude and, at least spiritually, think of their job as supporting rank-and-file drivers. They seem to take this philosophy very seriously, investing heavily in safety and driver training. Enrollees in WCN’s management trainee program will obtain commercial driver’s license, drive collection routes, and handle customer service calls before assuming P&L responsibility.

WCN’s unique operating model was brought to bear in its $4bn acquisition of Progressive in 2016. Progressive was a stodgy, top-down managed organization that chased volume at any cost, operating near break-even in many markets. Prime markets were starved of trucks, trucks were starved of maintenance. Progressive had terrible safety record, reporting 4x higher accident frequency than WCN. With morale understandably in the dumps, 40% of employees turned over every year (vs. just under 20% for WCN). After taking over this ailing property, WCN cut unsafe routes, pruned unprofitable contracts, raised prices, and reinvested in trucks and maintenance, which boosted driver morale, reduced turnover, and resulted in higher productivity and uptime. Within the first year, the low-single digit EBITDA margins of some markets were brought up to 18%-21%. Even as WCN purposefully shrank Progressive’s revenue from ~$2bn to $1.8bn, they lifted EBITDA from $480mn to $600mn and doubled free cash flow.

Of the $18bn of private company revenue in North America, WCN thinks $4bn could fit WCN’s markets and business model, so there’s plenty left to buy. At 2.5x-3x revenue (~10x EBITDA) and 2.5x leverage, acquisitions could absorb around 7 years of free cash flow after dividends. A multi-billion waste company with great assets and fixable operational issues like Progressive was really a one-off opportunity. These days the company is picking off like ~$150mn of revenue per year in well-run tuck-ins, adding ~2 points to its overall growth as part of a mechanistic value creation process similar to that of WM and Republic, with 4%-6% price-led organic growth and a bit of margin expansion fueling low double-digit growth in per share free cash flow. That is basically the end state for every successful waste management roll-up.

Along the way, though, things can get exciting.

Led by former minor league goalie, Patrick Dovigi, GFL (”Green for Life”) began operations in 2007 with 1 transfer station, 4 trucks, and $250k of starting capital. The company’s basic strategy was to make big platform acquisitions in new markets and then bolt on small operations to build route density, scale overhead, and supply more collection volumes to existing landfills. With $30mn of growth equity from Hawthorn Equity Partners (who made 24x its money from its first investment to its exit in 2018), GFL merged 3 small companies near Toronto. From there, GFL broadened its presence in Eastern Canada, carving out certain Canadian assets from Waste Management and then buying Matrec from Transforce in 2014 and 2015. They then breached the US market in 2016 with Rizzo Environmental, which at the time was subject to an FBI corruption investigation into “pay to play” schemes, news of which broke just weeks after the purchase, to Dovigi’s “shock” and “disbelief” (oops!). Patrick promptly cleaned things up and convinced all of Rizzo’s municipal customers to stay. At this point, GFL was 60 acquisitions deep, with 80% of its revenue coming from Canada.

In October 2018, with fresh capital from the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan, BC Partners, and GIC which valued the company at $5.1bn [Note: as of 4/8/22, BC Partners and Ontario Teachers still owned 11% and 28% of shares outstanding, respectively], GFL made its biggest bet yet, acquiring Waste Industries for $2.8bn. The purchase doubled GFL’s footprint, which now included a presence in 20 states and all Canadian provinces ex. PEI. Waste Industries had a reputation as one of the most disciplined operators in the space, in no small part due to the guidance of their COO Greg Yorston, a highly respected 20-year industry veteran who, upon assuming the role of COO at GFL, served as a nice complement to a hard-charging deal maker like Patrick, instilling rigorous attention to metrics, pricing, and margin expansion.

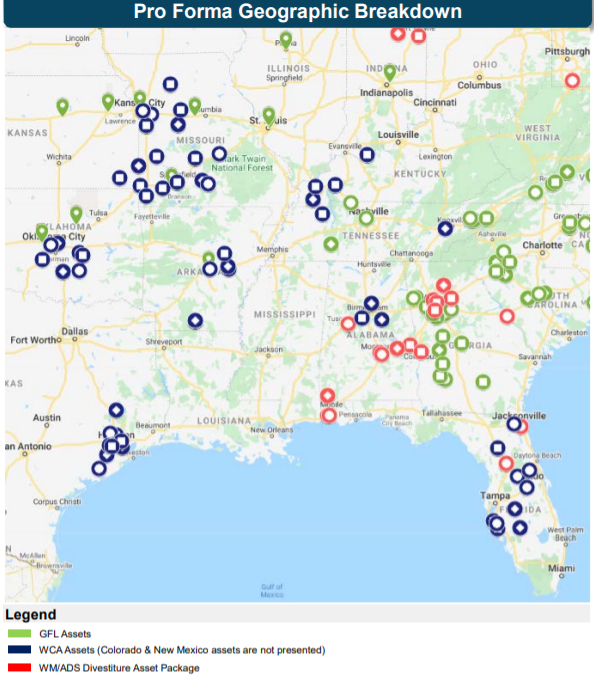

Following the merger, with its balance sheet more than 7x levered, GFL was constrained in its ability to do more acquisitions. So they raised fresh capital through an IPO in an early March 2020, just in time for COVID, and continued their debt-fueled acquisition spree, first paying $835mn for assets divested by Waste Management in its acquisition of Advanced Disposal, bolstering its presence in the Midwest, especially Wisconsin, which accounted for ~65% of EBITDA; then shelling out another $1.2bn for Macquarie-owned WCA, which brought a presence Missouri, Texas, and Florida. These back-to-back acquisitions provided a backbone to support roll-ups in new geographies and densified existing GFL/Waste Industries’ territories in the South and the Midwest:

Less than a year later, they spent another C$929mn on Terrapure Environmental, complementing existing footprint across Canada. [Note: Terrapure was an industrial waste business that Birch Equity Partners had carved out of Newalta in 2015 for C$300mn and used as a roll-up platform.]

Besides the larger deals, GFL did a bunch of tuck-ins that are too small to get into. This company is buying things all the time. They’ve completed 21 acquisitions, adding C$300mn of annualized revenue, this year alone (with 13 of those bought for less than C$5mn). They dispose of assets too sometimes. Notably, this past April GFL spun off its infrastructure division, a relatively low margin (14%) business that provides excavation and demolition services, to Green Infrastructure Partners, in return for a ~50% stake in the new entity plus C$1.25bn in cash, which will be recycled into solid waste acquisitions. Green Infrastructure is pursuing its own roll-up strategy, with plans to grow EBITDA from C$180mn (pro-forma for Green’s merger with COCO Paving) to C$1bn+ over the next 5-6 years.

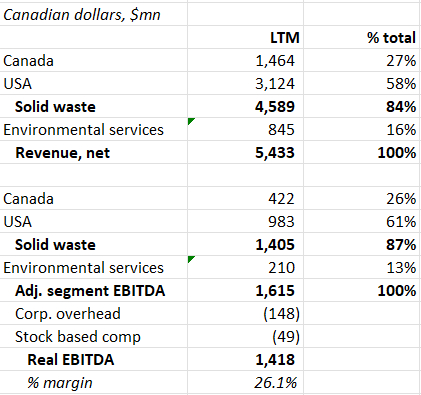

As of the most recent quarter ending March 2022, here’s where things stand:

The bulk of GFL’s revenue and EBITDA comes from solid waste collection and disposal in the US. Environmental Services consists of: 1/ liquid waste, where GFL collects used motor oil, antifreeze, and spill-off from petroleum and chemical companies and 2/ soil remediation, where GFL collects and cleans contaminated soil after demolition jobs. Also, last year, through some joint venture agreements, they started collecting methane gas from their solid waste landfills and selling it as renewable natural gas under long-term contracts, with gas pricing fully hedged. On growth capex of C$150mn-C$200mn, most of which will be invested in 2023, management expects its portion of free cash flow to be C$115mn-C$125mn, not huge but still meaningful on a total current free cash flow base of ~C$660mn.

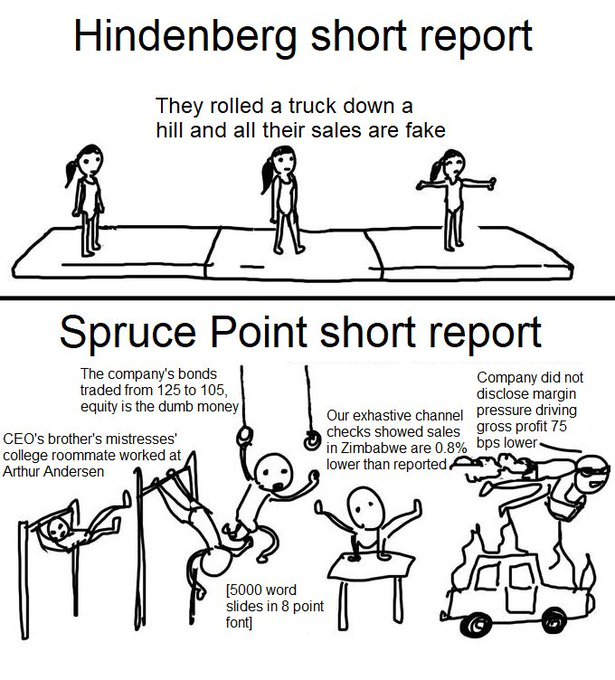

Waste disposal is an easy business to understand and the cash flows are durable enough to support a levered rollup strategy. As predictable as a waste company’s cash flows are the suspicions and short reports aroused by the concatenation of “levered” and “rollup”. Naturally, I’m thinking of Spruce Point’s August 2020 short report. The presentation was characteristically sensational and chock full of irrelevant details dressed up as shocking smoking guns. That Patrick once hired a guy who once had a Facebook post that was commented on by someone with mob ties implicates Patrick in…uh…what exactly? Or that the guy who runs a company that refurbishes GFL’s trucks is buddies with the drug dealing brother of the former Mayor of Toronto, has implications for GFL shareholders how?

“In one case, GFL bought a company that itself acquired 60 companies, making GFL a roll-up of roll-ups.” This is waste management ser. The whole industry is a roll-up of roll-ups. By this criteria, WM and Republic are suspect too. “We believe GFL is simply a financial motivated investment scheme that failed multiple times to IPO”. If by “financial motivated investment scheme” you mean a company, like you know, an entity that raises capital from investors, hires employees, acquires other companies, and provides a service to customers for profit, then yes, guilty as charged. And is postponing an IPO (in one case because private investors stepped in) really the same thing as “failing” to IPO? And is having a handful of minority investors during a 13 year stretch as a private company really the same thing as being “flipped around like a hot potato pancake among multiple owners”? And if you think you can trust GFL’s bucket shop underwriters, Spruce Point urges you to think again. This is the very same JP Morgan who kept Jeffrey Epstein as a client even after internal warnings! The very same Goldman Sachs that plead guilty to the 1MDB scandal!

This tweet from @MrtnzAlvrz succinctly captures the gist of what’s wrong with most Spruce Point research:

Still, just because I find Spruce Point’s work a little gross at times doesn’t mean there aren’t glimmers of truth worth taking seriously. For instance, SP points out that GFL churned through 4 CFOs since 2008, and pulls quotes from a former employee who had “ethical concerns” with GFL, relaying in a vague conspiratorial tone:

I have to say this very gently….a number of owners have come and gone and moved on. There’s certainly a group still behind the scenes pulling the strings at this Company and I’m not prepared to say any more about that.

Some of these concerns were echoed in this December 2020 Tegus call with the former Chief Operating Officer of GFL’s Solid Waste division. I don’t want to violate Tegus’ terms of service by posting quotes whole cloth from this interview, but to summarize, this guy claims that GFL’s current CFO, Luke Pelosi, is a yes man for Patrick and is no way qualified to hold his current position. He points out that 5 CFOs came and went during his 10-year tenure (he left the company in February 2017), encouraging the interviewer to “read between the lines”, and claims that some of the things going on at GFL – charging customers for non-existent tons, for instance – were beyond his ethical bounds. It’s possible GFL inherited shady activities from less sophisticated mom-and-pops and that these activities have since purged from the company now that it is under a whole lot more scrutiny as a public company. I don’t know.

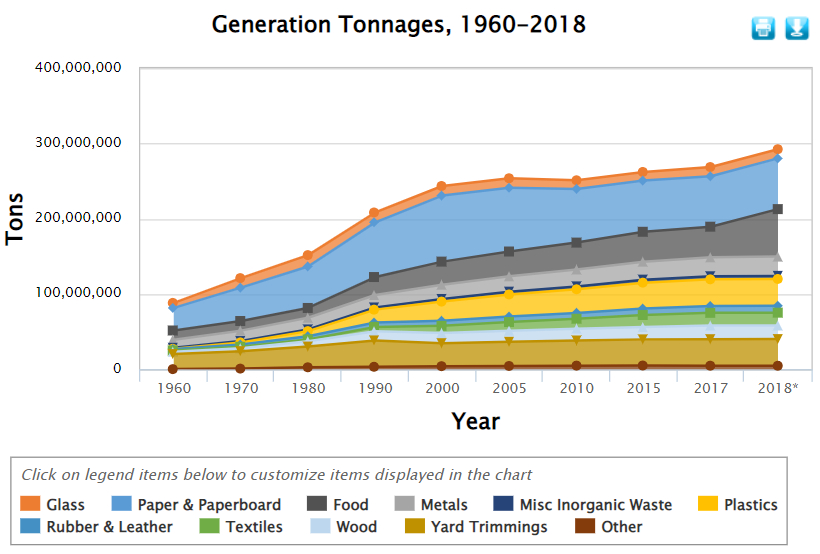

Spruce Point also describes GFL as an “aggressive roll-up”. They’re not wrong about that. Through its ~200 acquisitions, GFL has become the 4th largest waste management company in North America in just 15 years. They’ve tripled revenue since 2018, with the vast majority of that increase coming from acquisitions, and have spent more on acquisitions over the last 3 years than industry-leader WM, despite producing just 1/5 the latter’s revenue in 2019. Through just the first 5 months of this year, GFL is acquiring more annualized revenue than WM has added in any year from 2013 to 2020. Whereas acquisitions contribute ~1%-1.5% to growth at Republic, WM, and WCN, it’s more like ~25% for GFL over the last 2 years. I’m not worried about runway. One of the consequences of low entry barriers is that haulers will often spin up new hauling operations after selling existing ones to large acquirers, creating a perpetual supply of targets. According to GFL, 2,000 companies make up 70% of the Canadian market (vs. GFL’s 200 acquisitions since 2007 inception) and WCN believes private companies in North America still account for $18bn of waste management revenue. The recycling and solid waste management industry is estimated to generate nearly $70bn of revenue in the US alone, compared to ~$50bn of US and Canadian revenue across the big 4.

But something I’ve consistently heard is that GFL will buy anything that isn’t bolted down. Management claims they acquire tuck-ins for 5x-7x and large platforms for 10x-12x (maybe that whittle down to ~8x-10x after synergies), but industry folks are skeptical. Two competitors, including one that aims for high-single/low-double digit unlevered cash returns (with terminal multiple = entry multiple), told me GFL is willing to pay more for deals than they ever would, and the multiples that GFL says they are paying don’t appear supported by its consolidated returns. At year-end 2021, the company had C$20bn of gross capital. As of 1q22, their run-rate adjusted EBITDA, including EBITDA from acquisitions made through that point, was C$1.6bn, implying ~8% pre-tax returns, below the 10%-11% generated by its larger peers. But fine, let’s say GFL is in fact paying a premium 11x-12x+ or whatever for deals. Is that the same thing as “overpaying” for assets, as Spruce Point claims? The game here is to convert low but stable unlevered returns to attractive returns on equity using leverage. Debt is how the big 4’s miserable ~6%-8% after-tax ROICs translate into 11%-13% cash ROEs. You can pay more for deals and still hit ROE targets by adding more leverage. This gets dangerous beyond a certain point but given durable cash generative nature of this business, I think WCN, WM, and Republic are under-levered at 2.5x-3x more than GFL is over-levered at 4.6x.

I don’t own GFL but I see the appeal. Given the heavy fixed cost load from capex and interest, even 5% organic growth at 40% incrementals will get you to ~$800mn of free cash flow (US dollars) in 3 years against a fully diluted market cap of $12bn. If we assume acquisitions push revenue growth to 20% and free cash flow margins accrete to 12% (somewhat below WM, who has similar EBITDA margins but less debt), then we’re at ~$1bn of free cash flow. At 22x (14x EBITDA, assuming 28% margins and 4.5x leverage), the stock compounds at 23%/year, which is a whole lot better than than 10%-13% you might expect to earn from owning the other 3.

Of course, with GFL you’re assuming some added risk. The company is sitting on C$8bn of debt. A quarter of that floats and even with the weighted average cost across its debt at just 4.2% (down from 6.4% in 2019), interest expense consumes 20% of EBITDA, so a big rate move off these low levels could meaningfully dent profits. This risk is mitigated by lite covenants and evenly laddered maturities through 2029, with the first principal payment coming due in 2025. If they use free cash flow to pay down debt, the growth roll-up story comes to a halt and that probably won’t be good for the stock. But then again, in a high rate environment, they will probably be able to roll up targets at even more attractive multiples. I don’t know. Tough to say how that all shakes out.

The other thing to consider is that in terms of leverage and growth, I don’t think any waste manager has ever run this hot at this size, and even if there’s nothing shady going on at GFL it’s easy to imagine things slipping through the cracks and operational discipline deteriorating amidst the chaos of constant, humungous M&A. But I guess if there’s any industry where an aggressive posture is sustainable, waste management is it. The industry is built on levered roll-ups and there haven’t been any major blow ups that I recall. Casella Waste took a big impairment charge in 2001 on their KTI recycling acquisition; Waste Management famously cooked its books in the ’90s. But I can’t think of any colossal blunders in the last 20 years (can you?). GFL made it through its first 10 years geared 7x-8x. Today they carry far less leverage and, with industry veteran Greg Yorston running the day-to-day, they’re certainly in a better place operationally. I mean, they’ve acquired 200-some companies over 15 years and so far, nothing has really blown up in their face, except maybe Rizzo, and even Rizzo, the center of an FBI corruption probe, was set back on track. That seems like pretty good evidence that they’ve developed some muscle memory around buying and integrating acquisitions and/or that this is just a really hard business to screw up. Like Constellation Software has a standard approach to M&A, with base rates informed by decades of buying and operating ~500 software companies. And regardless of vertical, a software business is a very sticky annuity that can yield attractive IRRs when purchased at less than 2x maintenance rev. Constellation isn’t buying at 50x forward revenue and betting on a narrow range of hyper growth outcomes. I can imagine that in waste management too, deep experience applied to a business with attractive structural attributes (low churn, low cyclicality, predictable cash flows) means management can safely execute what from the outside may seem like a reckless pace of acquisition. Finally, Patrick Dovigi’s ~4% ownership of the company, worth ~$412mn+, comprises the bulk of his net worth. The guy lives large and likes nice things (he has said he buys a new car every 6 months), so he has every incentive to make this work.

Disclosure: At the time this report was posted, accounts managed by Compound Insight LLC (Scuttleblurb’s fund) did not own shares of any company mentioned in this report. This may have changed at any time since.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!