When I first took Tiago Forte’s productivity course Building a Second Brain (BASB) in April 2020, the concept I struggled the most to grasp was PARA. Short for “projects, areas, resources, and archive,” PARA is a system for organizing your digital notes around projects you’re actively working on. In turn, whether or not certain information inspires action becomes a filter for the kind of content you consume and save. Previously, my digital workspace consisted of tasks, files, and saved articles scattered across my desktop and various apps at worst. At best, they were grouped into arbitrary folders like business, psychology, and history—categories that resembled a college course catalogue. But my goal here wasn’t to get a degree in knowledge management or index the web. With PARA, in theory, I knew the acronym and its definitions. In practice, my attempt to perfectly set up this system for actionability was preventing me from taking action.

What was the difference between a “project” and an “area”? Was this a hierarchical or nesting situation? How would the system scale across different tools? Which app should I build this out with? These were inconsequential problems I convinced myself I needed to solve before venturing further into the course, believing that the lack of structure was the bottleneck for my personal projects.

It took me a while to understand that PARA was a framework that would emerge over a need and over time. I often took a case-by-case approach to my projects, customizing or adapting frameworks and workflows around specific contexts. Having experienced how too much structure early on could stifle more than scaffold, I was skeptical of systems that felt prescriptive and standardized to the point of being boilerplate. At the same time, I had felt how time- and energy-consuming it was to start every project from scratch, indecisive on how to save and resurface information for when I needed it.

Throughout the course, I noticed students often progressed through points of:

- Convergence - following the established frameworks and methods

- Divergence - forming your own frameworks and methods

In convergence, you implement the content to understand what works and doesn’t work for you. This looks like following step-by-step directions and mirroring workflows. In the process, you begin to internalize the principles behind a practice. From there, you’re free to reshape the rules, which you’ll realize were nonexistent to begin with. During BASB, I had focused on convergence. When things didn’t click, I assumed I needed to follow instructions more closely. It wasn’t until I rejoined BASB as an alumni mentor a few months later that I saw the concepts through the lens of divergence.

As I was preparing my weekly mentor sessions, I realized my earlier resistance to PARA had less to do with its instructions, and more to do with me ignoring my intuition. As I prepared my lesson plans, I thought about how I would’ve taught the concepts and the principles behind them to myself. In this way, the four-letter acronym now became the output, not the input.

That shift in perspective led me to create an exercise I’ve nicknamed “PARA on Paper.” Building on the PARA framework, this activity challenges you to write down what you need to get done on a single page. It’s a way to try out PARA at the smallest and most flexible level before scaling the system across software. From that blueprint, it becomes more intuitive to design and integrate PARA within existing workflows.

Since running and refining this exercise in BASB and outside of the course, I’ve had a chance to record the process, with the goal of showing how both personal and team knowledge management can be emergent and built just-in-time.

The PARA on Paper Process

Timing and Tooling

Before we begin, a few notes on how long the PARA on Paper process takes, and on what tools you (don’t) need.

Timing: I usually limit this entire exercise to 10-20 minutes depending on the size of the group, but feel free to adjust. While taking inventory of your current projects feels like it should be a time-intensive and thorough sweep, the constraint of a time crunch is intentional. When you only have a few minutes to list things down, you’re forced to let go of definitions and instinctively surface what’s top of mind—and often top priority. There’s just enough time to capture key points, but not enough time to get into the weeds. Only once you’ve set up the scaffolding can you go back in and fill the architectural gaps at a later time—but not a moment before.

Tooling: This exercise is intended to be done on paper (hence the name), but the idea behind it is that writing out PARA or any organizational framework down on one page allows you to visualize your work at the smallest, most flexible level before you scale it across more complex software. On paper, you can easily scratch, scribble, and move things around with a single stroke. Nothing is permanent, and therefore the pressure for perfection eases up. It can also be sobering to see the extent of your current and upcoming commitments laid out flat, unobstructed by dropdowns, folders, or backlinks, that might otherwise provide a false sense of prioritization and progress. Paper as a medium doesn’t have to be prescriptive either. Even a sticky note, napkin, or any no-frills text editor will do. I’ve tried dozens of note-taking and project management apps, but at the end of the day, I find myself returning to a notepad or Google Doc—at least to start. It lowers the hurdle between planning and producing to the point that I can step over it without worrying about tripping.

Begin with questions

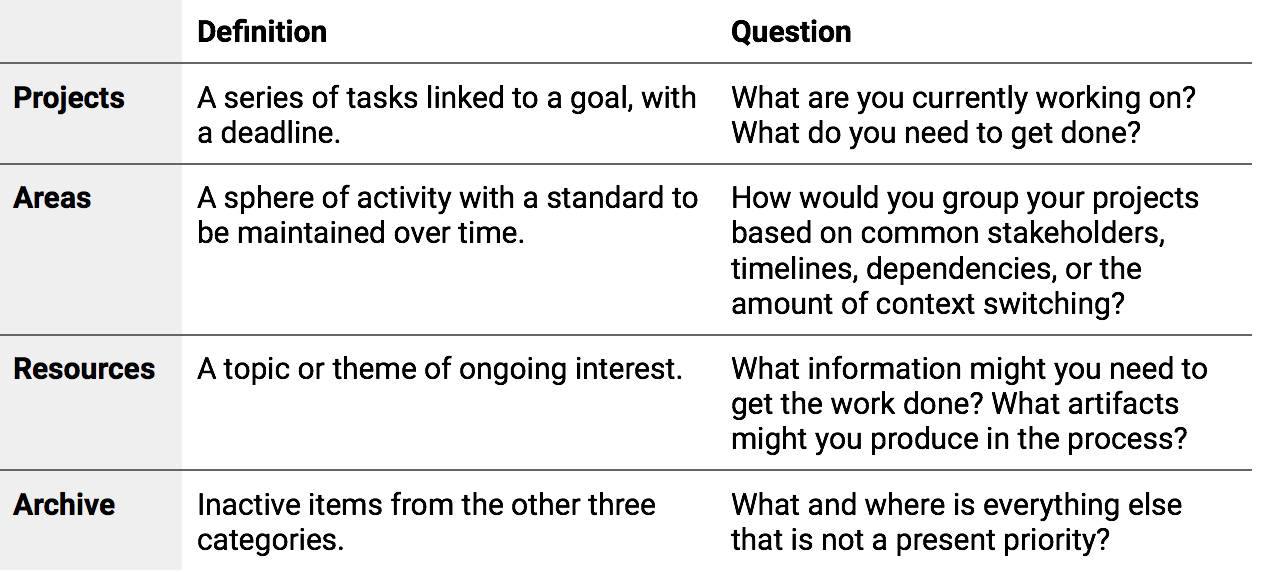

The first adaptation I made was reframing PARA from its original definitions to a series of guiding questions:

Question 1: What are you currently working on? What do you need to get done?

Suggested time: 5 minutes

A project preserved within the confines of your mind is in a perfect and protected state. But it’s also in its most ineffective form until you write it down. Starting with a blank page, the first step is to list out what you currently have on the go and what you need to get done, mentally scanning the upcoming week, month, and quarter.

Starting out, quantity precedes quality. There’s no right or wrong way to phrase each project, no rigid definition of what a “project” is, and no set number of projects you should aim to list. This is about getting ideas out of your head and onto the page. What gets forgotten is just as revealing as what gets remembered. The very act of writing down what you’re working on is the beginning of organizing your thoughts, and of taking inventory of where you’re directing your time and energy. Text is merely a placeholder for what you’ve always known, always wanted to do, but neglected to articulate.

Question 2: How would you group your projects based on common stakeholders, timelines, dependencies, or the amount of context shifting?

Suggested time: 2-5 minutes

Going through the projects listed earlier, notice the common themes and natural groupings. As you filter through your projects list with these questions, your Areas will emerge:

- From an energy management standpoint, which projects involve similar levels of context switching?

- Which projects when grouped together make the most sense?

- Are there shared timelines or dependencies between projects?

- Which projects have the most stakeholders in common?

- Which projects are routine versus one-off?

- Can any projects be combined, relegated to a task within a project, delegated, or eliminated?

Here’s what I wish I understood earlier: Areas aren’t so much defined in advance as they are discovered along the way. My first time in BASB, I followed along as others who seemed to know what they were doing typed out Projects, Areas, Resources, and Archive on a pristine Notion page. New pages were created for Areas like Home and Health, each with its own emoji, cover photo, and linked to a task list or kanban board. I did the same. By the end of the demo, I walked away with an aesthetic and intricately linked dashboard—which I barely revisited. Sure, Home and Health were relevant areas in my life, but they didn’t require a digital presence to be managed. By defining and scaling Areas on software before I had a view of my Projects, I wound up pigeonholing the latter.

Starting again, I began with only Projects and Archive (PA) this time, gradually adding Resources (PRA), before eventually getting to a point in my work that a need for Areas even arised. My version of PARA looked vastly different from the examples I saw, but it made sense to me and the just-in-time approach alleviated the need to have everything figured out before starting. With personal knowledge management especially, Areas can be as clear or cryptic as you’d like, categorized into a series of questions to explore or goals to pursue, to a set of emotional, mental, and physical states to maintain.

Question 3: What information might you need to get the work done? What artifacts might you produce in the process?

Suggested time: 3-5 minutes

In the process of completing your projects, write out the information you’ll need or questions you’ll answer along the way.

- What information, tools, or resources will you need?

- What deliverables or artifacts might you generate?

- Is there material you can repurpose from previous work?

Similar to Areas, I only create a heading or folder for Resources once there’s actually a file to go in it. Resources might include:

- Meeting agendas, minutes, and topic banks

- Facilitation guides and activities

- Standard operating procedures

- Research reports and briefing notes

- Stock photography, icons, and brand guidelines

- Calendars, run sheets, and contact lists

- Presentation and report templates

- Communication scripts and swipe files

Your Resources may look like creative residue, but they’re often the root of future creative output. Creativity and expression as an extension of knowledge management often get boxed into what generates the most noise: reserved for and synonymous with YouTube channels, podcasts, blogs, and other public, prolific forms of media. In contrast, a book highlight, a meeting summary, family recipe, map of a frequented trail, internal company newsletter, or personal mood board are quieter but no less valid as Resources and forms of creative expression. What gets overlooked is often what already exists, just not external facing. While Resources is less actionable than Projects and Areas in terms of order, I believe it is the most action-oriented way of remembering and reviving your past work.

Question 4: What and where is everything else that is not a present priority?

Suggested time: 1-5 minutes

Archives is the final category in PARA that tends to be the most straightforward to understand while taking the least amount of time to implement digitally. On paper, this is a step I skip. As the name and definition implies, anything and everything that isn’t a present priority and doesn’t fit the previous three categories goes into this separate folder. It’s low-risk: your files aren’t deleted, just dormant—and high-reward: your once-cluttered workspace has now cleared up. Out of sight, but still in mind.

Adaptations for team knowledge management

I’ve run variations of this exercise with teams, whether with a work, social, or volunteer group. You could also organize this with family. With teams, I recommend designating a facilitator to guide the group through the mostly silent sprint, as everyone individually lists out what they’re working on. From there, projects are pooled into a shared document, where the team discusses how to group them based on common themes, objectives, or priorities. The structure diverges from PARA and may resemble more of a RACI or Gantt chart, but the underlying concept of figuring out what you need to get done before building a system around it remains constant.

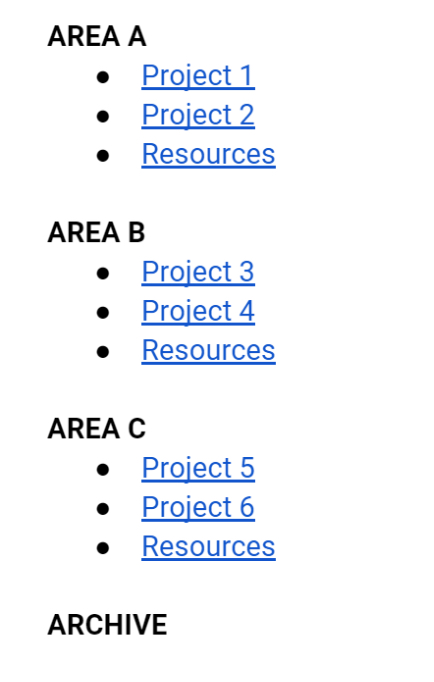

I usually start from an outline like this...

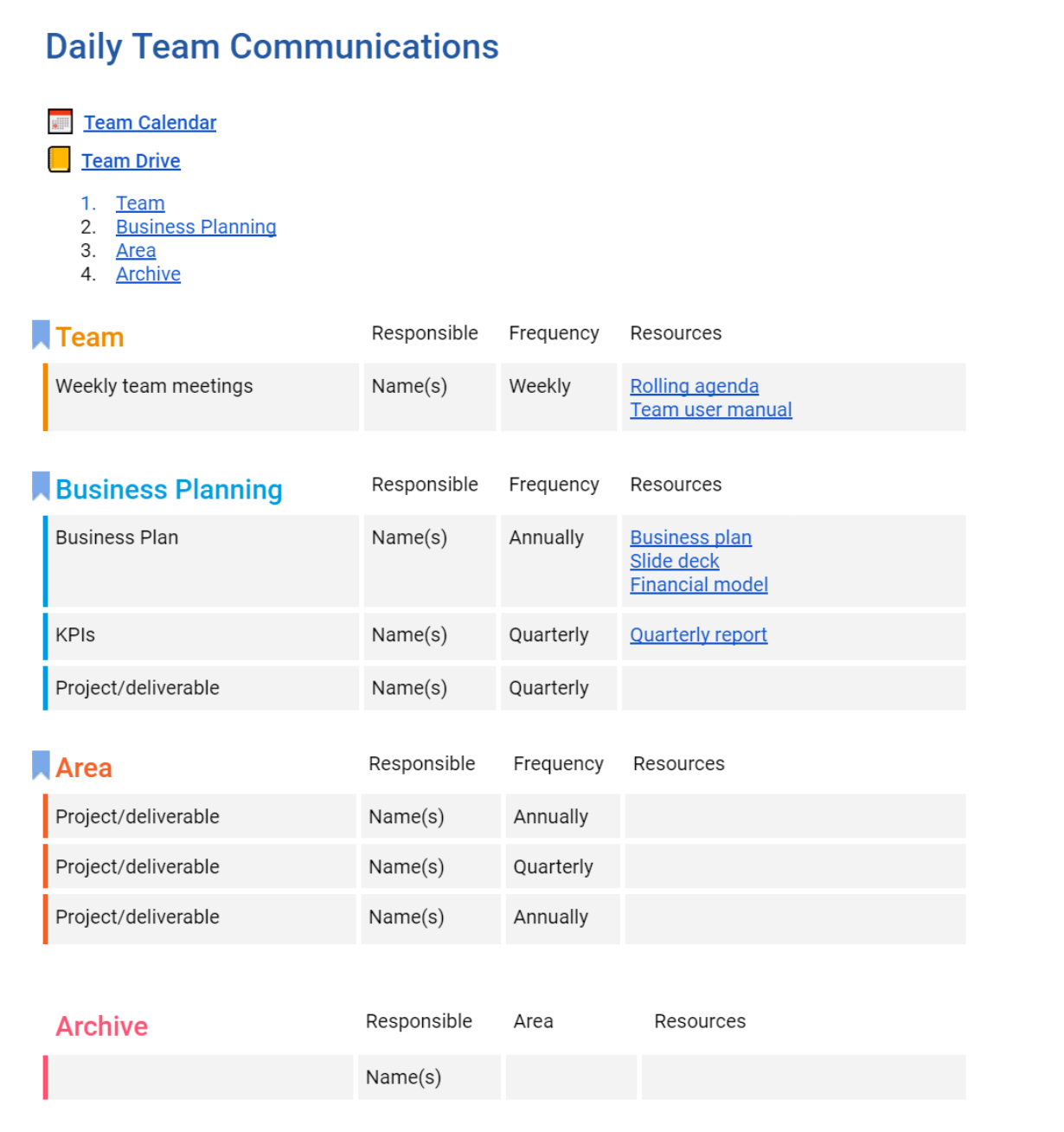

...before building out a basic project plan, which I’ve formatted in tables in this example:

For team knowledge management, I’ve tried various apps, but find that if the goal is adoption

and shared ownership, it works best to meet people where they are, using familiar tools. I usually create this on a Google Doc or Sheet, but all of it can be scaled to more sophisticated project management tools. If your team uses a shared drive, this setup can be mirrored across a folder system. The documentation itself becomes a tool that can be repurposed for one-on-ones, project meetings, and cross-team information or collaboration. While some people have successfully merged their personal and team knowledge management systems, I find separating work and personal projects maintains a healthy boundary between the two priorities, even if it means using different tools or accounts for each.

Knowledge management as a record of your discovery

The moment I realized I didn’t need PARA—or any organizational framework for that matter—in order to take action, was the moment I began to understand it. Even today, I spend most of my time at the projects and tasks level, with everything else in various stages of archive. By starting at the smallest, most actionable level, and only adding layers when the need arises, your time shifts from maintenance to making things happen.

Building a knowledge management system is about leaving a record of your discovery. An idea, once expressed in writing, is no longer just an idea, but something to inspire and take action on. Starting with an inkling of what you need to get done might not seem particularly remarkable, but making sense of it in writing is a remarkable feat. Ordering tasks into a plan is a remarkable feat. Communicating what that plan will help you create is remarkable. All of it is valuable, especially if you get it down on paper.

My unremarkable epiphany about knowledge management throughout all of this is that it’s about subtle shifts in awareness. Moving things from invisible to visible, private to public, and closed to collaborative. Whether that’s externalizing intuition into insights or making your projects and priorities known to yourself or your team, shared awareness can be used to show up for yourself, and help others show up at their best.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!