We are living in an era ripe for makers. While large, established players dominated technological progress in recent decades, the next big thing is much more likely to come from a tinkerer’s garage—thanks to generative AI’s accessibility, speed of prototyping, and massive market opportunities. My intuition is that it’s a historic moment on par with the birth of the Internet—or perhaps even more significant than that.

So it seemed like a good time to ponder what makes for a maker. Who is suited to the task of novel invention? What technological and societal circumstances do makers thrive in? And why is generative AI such fertile ground for maker magic?

📻 Who are makers?

As the word says, makers make stuff. They’re the inventors and prototypers who engage with a new technology not because they have to as part of their job, but because they find it irresistibly interesting and fun. They don’t do it for entertainment, fame, or promise of other future boons (even if they sometimes reap those benefits).

I like to say that developers are “9-to-5-ers” and makers are “9 p.m.-to-early-morning-ers.” This might not be an entirely accurate description, but it captures the spirit. It hints at the key property of a maker: it’s not a kind of person. It’s a mindset. The same person who puts in their work hours at their day job becomes a maker extraordinaire in the evening or weekends.

They get their hands dirty. They are the kind of early adopter who doesn’t just adopt the tech. They build new things with it.

Makers play with technology, rather than apply it to achieve business goals. They delight in finding weird quirks and twists, the same way gamers love finding glitches that lead to a speedrun. They find all the design flaws and unintended side effects and turn them into a feature. The whole process is messy and often follows the “life, uh… finds a way” path—what makers build may differ a lot from the technologists’ intended range of use.

Makers write crappy code and wire things on breadboards. They rarely care about the future enterprise strength of their project. They explore ideas non-linearly, probing all—however unlikely—possibilities. They scrap half-finished projects and repurpose them into new ones. All of this contributes to the seeming disarray of the maker scene. A good sign of a maker project are fix-forward collaboration practices, where any failed attempts at making progress are addressed by patching new attempts over them, rather than reverting everything back to the pre-failure state.

Makers are here to discover something new, to bravely explore. They crave being first to uncover some way to make technology do a thing that nobody else had seen before. Makers become increasingly more disinterested with a particular technology as it matures and becomes polished. Polish and reliability mean that the tech has become mainstream—and therefore less likely to yield a “holy crap!” moment.

🧫 The right conditions for the rise of makers

Although makers have always been around, there are certain eras when they shine, tied to the cyclical nature of technological progress. This cycle of technological innovation has been portrayed from different perspectives in a range of books.

In The Master Switch, Tim Wu proposed a rhythm of open and closed ecosystems alternating as new innovations emerge. Open ecosystems usher forth the beginning of the cycle, and then corporate interests co-opt the developments to extract business value. They eventually create monopolies (and thus “close” the ecosystem).

In The Innovator’s Dilemma, Clayton Christensen suggests that companies born from a technological breakthrough tend to become vulnerable to disruption from the next cycle of innovation.

In Crossing the Chasm, Geoffrey Moore outlines the innovation adoption lifecycle, where a novel technology or product is first driven by innovators and early adopters. It then needs to overcome challenges to generate broader adoption (thereby crossing “the chasm”).

I’d like to add another perspective to the mix: one focused on the role that makers play in this cycle. When a novel technological capability moves forth to acquire an interface, and a broader audience begins to interact with it, a question hangs in the air: “What is this thing actually good for?”

This is the value question. Whoever answers this question first gains a temporary advantage: until everyone else also figures it out, the first mover can seize the opportunity to acquire this value.

Makers arrive at the scene right about then. They start poking at the interface and make things with it. The amount of power makers will have at this point depends on whether or not they can answer the value question sooner than anyone else.

What are the properties of the technological capability (and the environment it’s introduced to) that put makers in the driver’s seat?

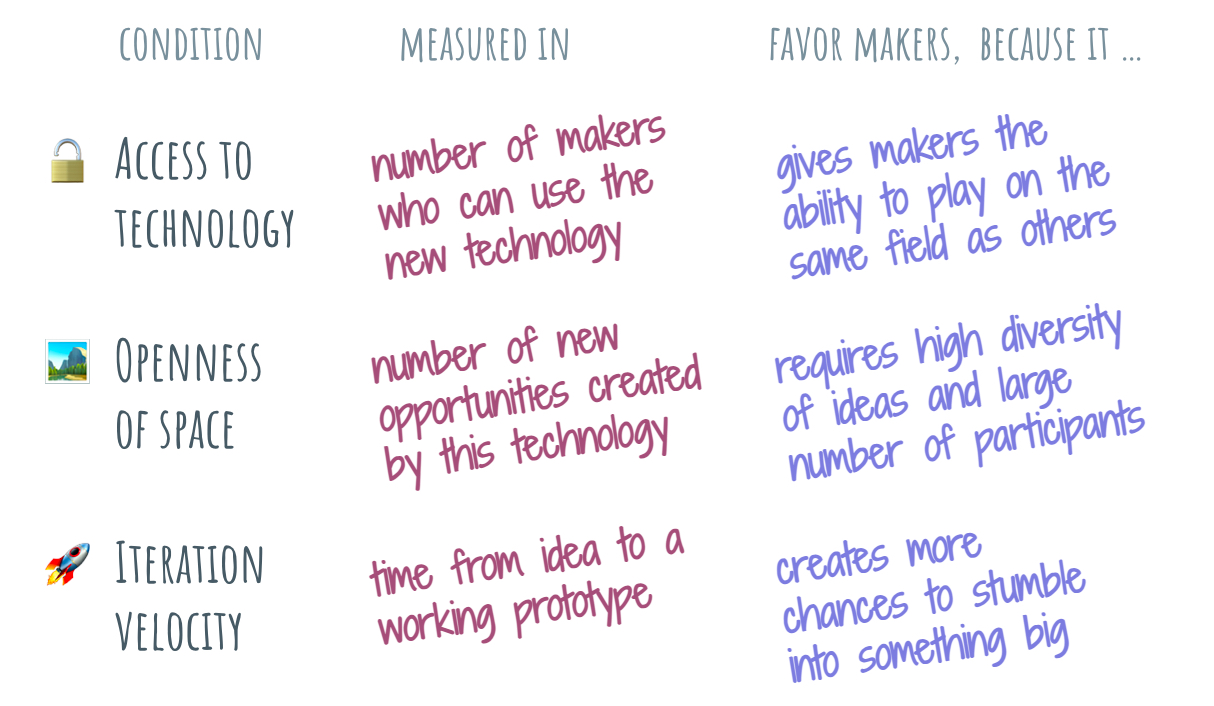

I’ve been thinking about this a bit, and I keep coming back to these three concepts: 🔒access to technology, 🏞️openness of space, and 🚀iteration velocity.

All these properties interact with each other, so they aren’t exactly orthogonal.

🔓Access to technology is both the property of new technological capability and its environment. It is probably best measured in the number of makers who could practically start using the capability (because it’s affordable, usable by the public, supported by adjacent technological advances, or other reasons).

An example is the introduction of widely available high-speed Internet. Without any discernible change in how the web worked, the increase in bandwidth created new opportunities for makers to spur what is known as “Web 2.0.”

🏞️ The openness of space is reflected by the number of new opportunities created by the introduction of the technology. Well-established players tend to be subject to their embodied strategies, leaving them unaware of vast portions of the space, and thus highly vulnerable to your usual innovator’s dilemma and counter-positioning.

One example is the shift to smartphones that happened with the popularity of the early iPhone. Incumbents like taxi companies were poorly prepared to deal with the new customer interactions enabled by mobile computers. As a result, apps like Uber and Lyft decimated their market.

A good marker of a wide-open space is that a typical market-sizing exercise keeps collapsing into a fractal mess, creating more questions than answers. It’s not just one thing that suddenly becomes possible, but a whole bunch of things—and there’s this feeling that we have only scratched the surface.

Open spaces favor makers, because they require high diversity of ideas and large quantities of participants to facilitate broad exploration of the space.

🚀 The iteration velocity is what gives makers the edge. Makers rule tight feedback loops. The shorter the lead times, the more likely makers will show up in the leaderboards. If something can be put together quickly, count the makers to stumble into a thing that actually works. Conversely, if the new technology requires lengthy supply chains and manufacturing processes, makers would play—at best—supporting roles.

Iteration velocity is also influenced by the level of stakes in the game. The higher the stakes, the less velocity we’ll see. For instance, we are unlikely to see makers experiment with passenger airplanes or power grids. Those are areas where the lead times are necessarily long. So no matter how exciting the innovation, makers won’t be able to play a pivotal role in those types of spaces.

📈 Makers rising

If we look at these conditions and compare them with what is happening in the space of generative AI, it becomes fairly clear that we’re once again entering a prominent maker era.

With open-source projects like Stable Diffusion and Llama 2, and online communities like Hugging Face, the access to technology is more or less 🔓barrier-free. For a maker, it takes only a little bit of effort to climb the learning curve and get going. Language models are no longer confined to the intricate frameworks and toolchains. Anyone can start playing with a large language model as soon as they want to.

The generative AI space is also ripe with opportunities—there are just so many ways in which this technology can be applied. It doesn’t take much effort to produce something interesting that nobody has thought of before. All that’s required is stepping out of the box and trying.

The space is so 🏞️ open that it’s not even confined to the minds of technology-savvy enthusiasts. I once quipped to my colleagues that English and philosophy majors are the most empowered actors in this space. After all, they are the ones who study how something like words and sentences come together— and the meaning that hides underneath them. Ultimately, language models are rooted in the most fundamental form of human communication.

The third condition is also clearly present. It takes at most seconds to interact with the large language model. This translates into 🚀 high velocity between tries: if our first idea didn't work, we can tweak and try again nearly instantaneously.

Such a strong presence of all three conditions points to the rise of makers. They’ll be the ones who first experience that moment of clarity, when a bunch of things loosely wired together suddenly becomes valuable.

The makers’ moment

Being a maker means being in constant search of that moment. When the thing finally works and goes viral on Twitter, and investors come knocking—it’s a maker’s dream come true. Often, it’s also the end of a maker’s journey. Once the new big thing is found, makers shift to become businesspeople (or they phase out).

The fun hobby project for one or two makers turns into a full-fledged team and company. Not all makers choose that path. After all, the thrill of exploration does get replaced by the mundane concerns of running the business. Those who choose to continue wield power to create and reshape entire industries.

I’m uncertain how long the maker’s era will last with generative AI. It’s possible that some of these transitions are already happening around us. Watch for hobby projects suddenly gaining funding and turning into communities and businesses. The makers behind them are the ones to pay attention to.

Following the beats of the cycle of technological innovation, these newly-minted enterprises will define how we interact and adopt generative AI as part of our regular lives. Their arrival will also herald the end of the brief moment of makers’ prominence—until, that is, the next cycle begins.

Dimitri Glazkov is a software engineer at Google diving headfirst into the complex world of strategy. You can find his writing on his website.

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

I thought Adafruit missed an opportunity when Radio Shack went bust. It would be nice to use some of the dormant commercial real estate for makerspaces, hefty ai rigs and 3d printers for hourly rentals, and retail parts. not to mention instructional space.

"Maker SO much better than "creator"!