Welcome to Cybernaut—an exploration of all things internet culture, from the idiosyncrasies of social media to the subcultures thriving and surviving in less frequented spots on the web. Subscribe for free to receive monthly long-form pieces like this one, and for Cyberbits, shorter, bi-weekly sendouts on everything from TikTok trends to random corners of Reddit.

A paid subscription gets you weekly Cyberbits, subscriber-only articles, access to the entire Every bundle of newsletters, and entry into our Discord community, where we discuss topics ranging from the creator economy and crypto to writing and recipes.

Hila Klein found out she was pregnant during a livestream with over 100K viewers. The live chat exploded:

“WHAT A SPECIAL MOMENT TO SHARE WITH THEM”

“Crying of happiness we got go share that moment with you”

“I hope it's a girl so she can be like our queen Hila”

Hila, and her husband, Ethan Klein, have amassed millions of followers on YouTube over the last decade as the duo behind h3h3 Productions and co-hosts of the H3 podcast. Initially building their audience through comedy sketches and reaction videos, in the past few years their channel has centered around discussions and interviews pertaining to pop culture, politics, and the internet. They’ve also become experts at living life online. Before the big announcement, they had shared their desire to conceive a second child, discussing their struggles with fertility and giving their viewers insight into doctor’s visits and specialist’s advice. In an earlier video, Hila mentioned that they would bypass the customary three-month waiting period before telling people about getting pregnant, intentionally eschewing the taboo of discussing a potential miscarriage—their audience would be the first to know.

For online creators and internet influencers, sharing intimate details about their lives is now part of the job description. The audience is brought into the inner fold on marriages, break-ups, divorces, deaths, births, adoptions, illnesses. Creators speak directly to the viewer’s eye line on video, spend hours with watchers on live streams, or croon into the listener’s ears through the podcast mic. The openness and candor with which many online creators speak is more than many average people would divulge to friends and family, and more than friends and family might divulge to them.For some, these information bytes form the basis of a parasocial relationship: instead of discussing a recent video posted by “someone they follow,” a fan might speak about “someone they know,” going so far as to refer to their favorite creator as a friend.

In 1956, Donald Horton and Richard Wohl coined the term “para-social relationship,” defined as a “seeming face-to-face relationship between spectator and performer.” Described in “Mass Communication and Para-Social Interaction,” they discuss these non-mutual relationships formed with people who appear on “radio, television, and movies”:

“The interaction, characteristically, is one-sided, nondialectical, controlled by the performer, and not susceptible of mutual development.”

The people capable of cultivating these relationships with an audience, described as “personae,” have specific skills and attributes that allow parasocial relationships to bloom with many people at once. “[The persona’s] appearance is a regular and dependable event,” and “devotees ‘live with him’ and share the small episodes of his public life – and to some extent even of his private life.” The result of these prolonged parasocial interactions is a bond between a fan and the object of their unreciprocated affection:

“In time, the devotee – the ‘fan’ – comes to believe that he ‘knows’ the persona more intimately and profoundly than others do; that he ‘understands’ his character and appreciates his values and motives.”

Horton and Wohl’s analysis does more than just hold up; it’s a prescient description of a phenomenon that occurs more frequently in our current age than in the one that came before. Their description of parasocial relationships—penned over six decades ago with Hollywood stars, television actors, and radio hosts in mind—feels like it was written about the current crop of online creators: the gamer hosting nightly streams, the podcaster dropping a new episode every Tuesday, or the daily vlogger revealing their morning routine.

But before the internet minted digital-first celebrities, the late ‘90s and early 2000’s marked the rise of reality television. The Real World premiered in 1992, following the lives of a group of young adults living together under the glare of non-stop filming in a single location. The voyeuristic view into their lives was compelling to audiences, as were the “confessional” segments where housemates spoke directly to the audience at home, chronicling their experiences in the house and in life.

In 2000, both Survivor and Big Brother premiered in the United States and viewers got to tune in for two things: the high-stakes competitions plus the quest for cash and the inner looks into the lives of the players—the clash of characters, the budding romances, and their “diary room” segments divulging secrets to those tuning in. On Big Brother, you could watch it all on-demand with the 24/7 live feeds that let you see into the house in between the airing episodes.

Soon enough, many reality television shows dropped the pretense of competition and would go on to focus on personality. The Simple Life with Paris Hilton and Nicole Richie first aired in 2003, chronicling their experience as wealthy out-of-touch elites navigating the challenges of the working world. The Simple Life would give rise to more “personae” driven reality television shows: Keeping up With the Kardashians, Jersey Shore, and The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills, to name a few. The rise of personality-driven shows changed viewers' expectations of intimacy with both reality stars and traditional celebrities. Their private lives—innermost thoughts, opinions, personal relationships—were displayed for our entertainment. The all-access pass into their lives has deepened parasocial relationships and made them more widespread.

A direct line can be drawn between reality television stars hooking viewers with their personalities rather than any obvious talents, and the rise of the internet star. Shows like MTV Cribs provided a look into celebrity mansions, prepared us for YouTuber house tours and content filmed in someone’s home. Interpersonal dramas between castmates as entertainment is akin to influencer beefs and online spats. Falling in love with contestants primed us for falling in love with creators.

In 2000, the same year that brought us Survivor and Big Brother, Eminem released the song “Stan,” about an obsessed fan who kills himself and his girlfriend when the rapper doesn’t respond to his litany of letters. The song is an acknowledgement of extreme fandom and its discontents in a time where Perez Hilton was beginning to blog about celebrities with a new rabidity, documenting their every move and demanding access to all parts of their lives. Today “stanning” creators is both explicit and ironic acknowledgement of extreme creator worship: writing fan fiction, creating fan pages, and tracking their movement across the web and irl. The word made it into the Oxford English Dictionary, eighteen years after the song was released.

But parasocial relationships have changed in one important way: more and more, the person on the pedestal reciprocates, and a perceived bond can become a “real” one—brief and impermanent, significant and long-lasting, or somewhere in between.

In a 2017 paper on the subject, researchers at Singapore Management University and National University of Singapore describe how the rise of social media has created online relationships between celebrities and fans that are more symbiotic than parasocial:

“Opportunities for interactions with celebrities in the past were rare and carefully controlled by celebrities for publicity and promotion purposes. However, social media have changed this one‐sided relationship to a more interactive and reciprocal one. Celebrities willingly share on social media seemingly personal information with their audiences. In response, audiences ‘follow’ their favorite celebrities 24/7, peeking into their private lives and getting to know them ‘up close and personal.’ These new media environments have narrowed the distance between audiences and celebrities and have altered the role of audiences from that of mere spectators or admirers to ‘friends’ of celebrities.”

While their analysis speaks to traditional celebrities’ use of social media, this dynamic is even more prevalent with “online celebrities”—their digitally native counterparts. There’s a rule that applies to anyone hoping to generate money as an online creator: people who hate you might follow you, but they won’t pay to support you. Hate-watching might drive views, clicks, and ad revenue, but this is hardly a sustainable model when the threat of an adpocalypse is always looming and platforms like YouTube can opt to demonetize your content. Influencers and online creators rely on true fans to generate their income. And it’s not churned subscribers, occasional listeners, or infrequent watchers who enrich creators; it’s the die-hard fans who long for intimacy and hope for interaction who stay longer and keep coming back.

Looking to monetize these parasocial interactions, creator platforms like YouTube, Twitch, TikTok, and OnlyFans are building features to allow creators to cash in on their parasocial relationships and help them cross the chasm between engaging with fans and initiating the valuable bonds that feel more like friendship. Increasingly, “supporting a creator” is paying for more intimacy and greater access. Though the result of this shift—for fans and creators alike—can be a connection that feels just as real as the truest friendship, the blurred lines of parasocial relationships can be dangerous. We’re not just living in the creator economy; we’re part of a parasocial economy that commoditizes closeness. Parasocial relationships can become parasitic.

Parasocial Interactions on Platforms

Across different social networks, creators are intensifying parasocial interactions with their audiences, often with the assistance of the tech platforms themselves.

YouTube

Nowhere is the phenomenon of parasocial interactions more obvious than on YouTube, where many creators trade their most personal stories for our parasocial engagement. On the H3 podcast, the creators refer to their legion of viewers as “The Foot Soldiers” and often incorporate them into episodes—they can call in and tip on live streams to have their questions read aloud. Fan memes shared in the show’s official subreddit are frequently discussed on the show. Several of the h3h3 Production’s employees were hired after being long time fans of the show; what was one-sided became mutual, what was virtual became real.

With “storytime segments,” YouTubers—mostly women—sit down in front of the camera, often in their bedrooms, and divulge the most intimate stories in their arsenal: abusive relationships with narcissists, friendships turned sour, or cringe-worthy first date stories.

These segments, anywhere from twenty minutes to two hours, are breathlessly retold with the YouTuber often vacillating between tears and incredulous laughter. In parting, the storyteller frequently hints to their audience about even juicier stories. Subsequent storytimes are, in part, chosen or requested by viewers who want more.

Tana Mongeau, one of YouTube’s most popular creators, propelled herself to infamy and nearly 5.5M subscribers with her many storytime videos, from “MY STALKER BROKE INTO MY HOUSE: STORYTIME” to “finally opening up about growing up/my insane dad.” Tana’s storytime videos are a direct conversation with her audience; she often lets viewers choose what she shares next. The parasocial bonds she’s established have made way for brand sponsorships with companies like Fashion Nova and a reality TV show with MTV. When she launched an OnlyFans in May 2020, promising an “uncensored” version of herself—the launch received so much traffic during an attempted livestream that it allegedly crashed the website.

But storytime videos are just one of many formats on YouTube that cultivate a parasocial dynamic. During mukbangs, a popular format that started in South Korea, creators “share a meal” with subscribers; during extended vlogs, they show their entire day from wake-up to wind-down. In popular tag videos, often suggested by fans or fellow creators, YouTubers lean into intimate content like “what’s in my bag,” “what’s in my fridge,” “the boyfriend tag,” and “the house tour.” These formats allow viewers into an influencer’s belongings, homes, and relationships, providing unrivalled access to the lives of people on the screen. They might do fitness, cooking, DIY, or makeup, but access to their lives is often what has made these creators famous in the first place. Much of the skill that creators possess is producing compelling content that centers themselves; they’re famous because they share, not sharing because they're famous.

Between uploads, YouTubers use the arsenal of social tools available to them to stay connected with their audience and take them behind the scenes—whether that’s Twitter, Instagram, or Patreon. On Instagram, followers get a peek into different sides of a creator’s life: the edited highlights on their feed and the unvarnished side on Stories. This duality is conducive to parasocial relationships, letting followers see the people they follow as “whole” or “imperfect” only makes the relationship seem more real.

In Q&A videos, often a paid perk on Patreon, parasocial relationships are blurred as viewers ask questions that their favorite creator responds to on video. Often, a question is preceded by a compliment or a declaration of affection: “I love you so much!” “Awe, thank you,” the creator says, “I love you too.”

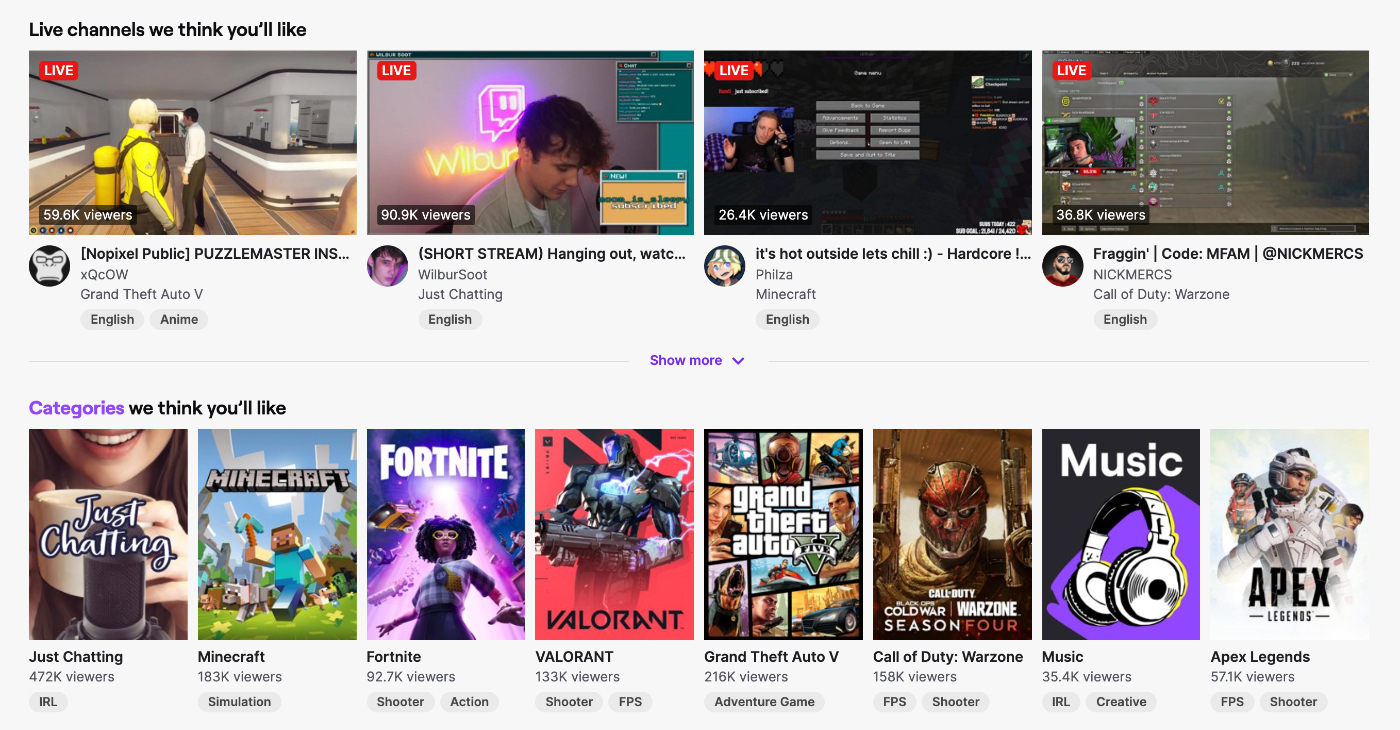

Twitch

On streaming platforms like Twitch, the intimacy and closeness found on YouTube can reach new depths. While YouTubers upload videos anywhere from 20-60 minutes, it’s not uncommon for gamers and streamers to go live for five hours straight, the live chat feed running the entire time—while they eat, take breaks, and talk to people off-screen. Whether it’s Ninja playing Final Fantasy, audio ASMR, or the growing crop of hot tub streamers, live streams are eating the internet; the eSports market is set to surpass $1.5B by 2023. The parasocial relationships that develop between streamers and viewers is undoubtedly part of this success.

In r/Twitch, a man expresses his concern about parasocial relationships he’s developed with the streamers he follows and supports, questioning what a “healthy viewer-streamer relationship” looks like:

“Lately I've been feeling a lot of emotion towards the streamers I regularly donate to. I love them dearly, and it almost feels like we have a real friendship. Realistically, I know these are very one-sided relationships and not actual friendships, but my emotions tell me otherwise. It feels real, and that's scary to me. At the end of the day, I don't know how they actually feel about me when they go offline. I want to be respectful and don't want to overstep any boundaries, I don't want to make anyone uncomfortable by getting too emotionally attached.”

The responses are mixed. While some Redditors sympathize and commiserate, others see the OP’s attachments as unhealthy, suggesting he “seek professional help.” But the most interesting responses are from streamers themselves who confirm that these parasocial relationships can be more than one-sided. A self-described “empathetic streamer” writes:

“....I end up getting attached to alot of my viewers, it can be good or bad. Let the streamer know you really enjoy their content and maybe try to make some simple interactions outside the stream, which im sure they will respond to politely. If you dont act over intrusive on them you could definitely befriend them in my experience.”

Another streamer suggests the same:

“I have become very close with some of my viewers. One is my best friend.”

One full-time streamer confirms that these interactions aren’t always as one-sided as they appear:

“....I personally feel very touched by people who contribute. It makes me emotional at times to see support because it means that I am affecting people positively which is my goal. Realistically I cannot maintain many close relationships/friendships off stream, but I honestly feel a connection to my regular viewers while streaming.”

TikTok

On first glance, forming parasocial relationships on TikTok might seem harder for creators. TikToks are short, and in many of them, creators don’t even speak—they’re dancing, lip syncing, or they’re dubbed by a popular song or meme format.

But very loyal fandoms amass on TikTok, and show signs of expanding beyond the platform. Some of TikTok’s top creators, like Addison Rae and Charli D'Amelio, have an uncanny ability to cultivate interest in their lives through existing formats (popular songs, common choreography, and memes), which has led to millions of followers and success beyond the platform, from movie deals to reality TV show contracts. Unlike traditional celebrities, TikTok ingénues aren’t especially aspirational; a TikTok star gets her power from being almost aggressively normal. Feeling close to her is obvious—she could go to your high school. She’s you.

TikTok’s creative formats can provide powerful glimpses into the lives of others. 30-second pranks let us meet a creator’s family—their tricked boyfriend, unsuspecting sibling, or befuddled father. Through the portal of the vertical video, we can see the backdrop of their bedroom, the streets of the city they live in, or the behind the scenes at their day job. Without all the rambling you find on YouTube, scrolling through these quick hits of intimacy feels like walking through an apartment building with no doors.

Some trending formats are darker. With popular sounds like “Hey Yo, something traumatic happened that changed my life check,” creators share catastrophic injuries or painful experiences. More recently, with the “My mom, there's no one else quite like my mom” trend, TikTokers share everything from their experience with Munchausen by proxy to being coerced into crimes by their mothers, complete with receipts.

Even the language on TikTok has evolved to acknowledge these parasocial relationships with creators: viewers often refer to TikTokers as “bestie,” often when they’re providing critical feedback to soften the blow and demonstrate they care about a creator—despite not actually knowing them. “It’s getting harder to defend you, bestie” is a common retort to social faux pas and bad behavior.

For its part, TikTok’s features encourage creators to reach across the follower-friend divide, making these parasocial relationships, even briefly, feel like the real thing. Introduced in 2020, a popular feature on the platforms allows creators to “Stitch,” giving them the “ability to clip and integrate scenes from another user's video into their own.” Features like this allow for a wide range of reaction videos and interactive videos. They’ve also allowed creators to respond directly to their fans: There’s a chance that Lizzo might just stitch your TikTok with her reaction to you singing her song. It might seem—and certainly does to the fans—that having a creator stitch your video with their own is a social interaction, not a parasocial one. But the creator is using the fan's work to fan the flames of their loyalty, and they're making money doing it. The fan just gets the feeling of being seen.

Cameo, which launched in 2016, is one of the most direct examples—and one of the earliest—of how even traditional celebrities see the economic opportunities of blurring parasocial lines. Brian Baumgartner, who played Kevin Malone on The Office, reportedly made over $1M on Cameo in 2020. In July 2021, it was reported that TikTok is testing “Shoutouts,” a Cameo-like feature that would allow creators to accept payment for recorded messages to their followers. In the near-present, TikTokers might sing their fans Happy Birthday, wish them well on graduating from school, or send well wishes about a break-up—words a friend might send, but for a fee. Features like Shoutouts sell access and intimacy, trading on parasocial relationships and their hold on fans and allowing, even briefly, for the line to fade, creating less distance between creators and their followers.

OnlyFans

OnlyFans, a content subscription largely associated with sex work and access to not safe for work (NSFW) content, has generated $390M in revenue between November 2019 and 2020. No other app has so successfully monetized the phenomenon of parasocial relationships. Aella, a top 0.08% OnlyFans creator, suggests in an episode of Means of Creation that the success of the platform is largely due to the way parasocial relationships are advanced through specific features and UI/UX:

“With OnlyFans you don't get to see the other men and OnlyFans is structured in a way to make it feel like you're getting private attention when very often you aren't. For example, when a girl sends a mass DM you don't know that it's mass… and you think that's for you, especially if it's a girl with a lower subscriber count. So OnlyFans was specifically designed to eliminate the competitive aspect to make you feel like you have a one-on-one…”

By simulating real one-to-one conversations, subscribers can feel like they’re engaging directly with an OnlyFans creator on the platform. Many OnlyFans creators have described making a percentage of their income from tips and requests, where individuals can request specific photos or videos for a price, deepening the impression that a creator is there for you, and you alone.

The Danger in Making Your Fans Your Friends

For creators, forming parasocial relationships with fans, and subsequently reaching across the divide, can encourage eyeballs and engagement in a time of fleeting attention—securing subscribers, landing sponsorship, and guaranteeing income. Siyoung Chung and Hichang Cho have suggested that parasocial relationships between influencers and fans can be financially favorable:

“(1) parasocial relationships mediated the relationships between social media interactions and source trustworthiness, (2) social media interactions influenced parasocial relationships via self‐disclosure; and (3) source trustworthiness had a positive effect on brand credibility, which, in turn, led to purchase intention.”

By building trust through parasocial interactions that divulge personal details, creators can convince their audiences to hit that like button, buy that merch, and subscribe. Take podcasts. The intimacy of another person’s voice accompanying you throughout your day, and the dependence this companionship can breed, are highly monetizable; IAB’s U.S. 2021 Podcast Advertising Revenue Study reported that podcast advertising generated $842M in 2020, up from $708M in 2019. Hosts typically read the ads directly to their audience, providing their personal endorsement of a product. In some ways, this is no different than how celebrity endorsements have worked for years. But when you consider that many listeners have come to depend on podcasts to help them fight loneliness, and that streaming rose during the pandemic, you can see how podcasters have been able to utilize the bonds of parasocial relationships in a way that is quite new.

In some ways, interacting with a creator can be like interacting with a friend. In modern-day parasocial relationships, we can connect with creators in the precise ways we do with our real friends—responding to their tweets, commenting on their Instagram posts, and even texting them. Compared to the parasocial relationships of the past—mediated through television screens, theatre stages, and radio waves—modern day interactions feel more organic, intimate, and integrated into our everyday lives, in no small part because our “real” relationships are already increasingly virtual. In a sense, our friendships and familial relationships can resemble parasocial ones—texting from the same room, likes and RTs to show affection and support—further blurring the line between the two. By engaging with creators in familiar ways, some find that they prefer the parasocial connections that are less costly than true relationships, with their messes and complications, and where “showing up” requires more than clicking a link or liking a photo.

Horton and Wohl suggest that while parasocial relationships are normal and can live alongside real relationships, “extreme para-sociability” is a pathology that can develop for (in terminology that reflects the time it was written) “the socially isolated, the socially inept, the aged and invalid, the timid and rejected”:

“The persona himself is readily available as an object of love—especially when he succeeds in cultivating the recommended quality of ‘heart.’ Nothing could be more reasonable or natural than that people who are isolated and lonely should seek sociability and love wherever they think they can find it.”

Fast forward to today, and while the claims that we’re in a “loneliness epidemic” might be overstated, there’s some evidence to show that “in richer countries, younger people are more likely to report feeling lonely.” This particular demographic are among social media’s most active users.

Other reasons for parasocial interaction might be more self-serving. Purchasing something a creator claims to use gets an audience member from enjoying an influencer to emulating them; adopting the life of someone you admire is just a purchase away. We're in a time where everything is for sale and creators are continuously finding new ways to monetize, including platforms like NewNew that lets fans control creators, exerting their will over their lives, deciding on both arbitrary and significant life decisions. Some creators are willing to make the trade.

The “extreme para-sociability” that Horton and Wohl first described in 1956 appears easy to observe through fandoms and “stan culture.” The parasocial relationships that creators are compelled to continue to maintain their fandom is in part an algorithmic problem—platforms reward engaged creators with greater visibility, while this in turn perpetuates unrealistic expectations from fans.

Burn Out or Fade Away

The need to always-be-uploading—releasing videos, creating TikToks, providing glimpses of their lives through Instagram—has led to significant creator burnout. At a certain point, many creators need to step back from punishing upload schedules and take a break from living life online. In 2018, popular YouTuber Lilly Singh stepped back from her daily vlogs and weekly uploads citing burnout. PewdiePie once released a video of his own titled “I QUIT (for now) [END]” sharing his struggle with feeling “forced” to create content:

“I feel really sad. I really feel down right now. Because I realized last night that I can't keep doing the vlogs. It really, really sucks…the fun disappeared somewhere…I just can’t keep going with it. I’m really sorry…”

PewdiePie took a short break from YouTube following the video, but has remained one of the internet’s most prominent creators. Other creators, struggling with the same problem, don’t always find their way back to the platform or return in a reduced capacity, losing their audience in the process. Some of this upload pressure arises from fans who regard content from their creators as “regularly scheduled programming”—a television show they can tune into at a predetermined time and get a dose of what they love. But television shows have production budgets in the millions and hundreds of staff members. Often, online creators are a one-person show: they’re the talent, finance department, film crew, production staff, editor, and marketing team. Even as they scale, some creators resist help, fearing the authenticity and specificity that made them successful in the first place would be lost in the hands of someone else.

Never Change

In many ways, viewers also treat very real online creators in the same way they treat characters on sitcoms or reality TV. Turning to our favorite shows for comfort, we blanche when a storyline seems implausible or we think someone starts acting out of character. Viewers might skip a hated season or abandon a show altogether—they are emotionally attached to the character they thought they knew.

Similarly, if a creator’s personal growth and life trajectory don’t align with fan expectations, viewers revolt. Creators—often quite young—naturally change and evolve, as we all do, but are incentivized by their viewers to stay the same, creating a feeling of cognitive dissonance that contributes to burnout. Creators start off as being their authentic selves online, but as time wears on, they end up playing a caricature of their former self.

After being one of the fastest growing creators on YouTube, Liza Koshy stepped away from the platform, making mention of the pressure to stay the same:

“I went into this spiralling dialogue, thinking people are going to hate me for doing something different. I read things online that weren’t the nicest things, I started being even more judgmental and not so nice in my head.”

Escalating Access

Over the years, YouTubers like David Dobrik have had to warn fans repeatedly about not coming to their homes, invading the space where they live requesting selfies, autographs, and conversation. The line between watching a glamorous movie star on the big screen and visiting their home is clear and distinct. But seeing the homes of creators in their videos, watching as a favorite creator surprises fans with cars or hangs with them on Omegle, that line becomes blurry. This escalating access breeds a dangerous familiarity that makes hopping on a plane to pay a creator a visit seem like a good idea. It can make fans feel a sense of entitlement to intimate access, even a sense of ownership.

This phenomenon is common across YouTube and represents a security concern for many creators on the platform; in 2017, YouTuber Julien Solomita pleaded with fans not to come to the house he shares with his girlfriend, fellow YouTuber Jenna Marbles. Being “relatable” and seemingly “accessible” online carries the real risk of attracting those who fail to understand boundaries, full-fledged stalkers, or those who want to actively cause harm, like in the tragic case of Christina Grimmie, a YouTuber who was murdered at a meet-and-greet in 2017.

Parasocial relationships can be dangerous for followers too. Between creators and their fans, there’s a power difference when it comes to fame, wealth, and influence. Some creators have taken advantage of this dynamic to push overpriced merchandise and scammy brand partnerships. Others have used fan’s devotion against them with greater consequences. By recognizing that contact would be desired or exciting, creators have used the dream of the parasocial dynamic—that it will one day become real—to engage in inappropriate or illegal relationships with fans, even soliciting sexual images from minors. Fans particularly on platforms like TikTok and YouTube are young and impressionable.

In these cases, the very parasocial relationships that cause harm can keep it going, even once it's called out and identified. A fan base’s trust and loyalty buys grace and leeway for creator behavior, at times blooming into full sycophancy. Someone's favorite creator can do no wrong; their fans are willing to defend the indefensible, rendering them uncancellable. Parasocial relationships don’t just empower, they embolden.

More often though, the harm of parasocial relationships is much more subtle; the expectation to respond, the obligation to provide intimacy at scale. Some creators are reckoning with the webs they’ve inadvertently woven. Jschlatt, a streamer and YouTuber providing commentary on Call of Duty, once shared his frustrations with parasocial relationships:

“My shit is a fucking tv show. The TV show will never love you, the characters have no idea who you are, they're not even real. And that's basically it and it sucks because this channel is kind of a contradiction of everything I just said and it feels kind of hypocritical for me to have this channel while also maintaining that I don't want people to get too attached to me as a person. And that's what I've been struggling with. It's definitely a gray area and I wish it was an easier situation to kind of reconcile with in my head. But it's not.”

Since posting this video on December 25, 2020, he’s largely been inactive across his two YouTube channels and has ceased regular streaming since last year.

His subreddit, r/jschlatt remains active, including a discussion on the very parasocial relationships that the creator discussed so bluntly:

“I appreciate Schlatt for doing this. It hurts to hear initially, that someone who you respect and look up to doesn't care about you as a person, not out of malice but just because of the reality of how being well known works. But it's important for a content creator to say.”

Despite how blurred the parasocial lines may be and how hard platforms are working to erase them entirely, the reality is rather simple: the notion of a special bond with a creator is contrived, and what seems like unfettered access to their lives is curated. It’s the intimacy you’d get from any imaginary friend.

This piece was edited by Rachel Jepsen.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!