Hi, Dan here. Superorganizers has covered Flow a lot recently, most notably in our profile of Chef Frank Prisinzano, who credits it with saving him. Flow is essential for anyone who wants to live a rewarding life, but it’s often misunderstood. So today we have a guest essay to explain Flow and memorialize its discoverer, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, who passed away recently. It was written by MC, the author of Flow State, a daily newsletter that recommends two hours of instrumental music to work to. I think you’ll love it. Enjoy!

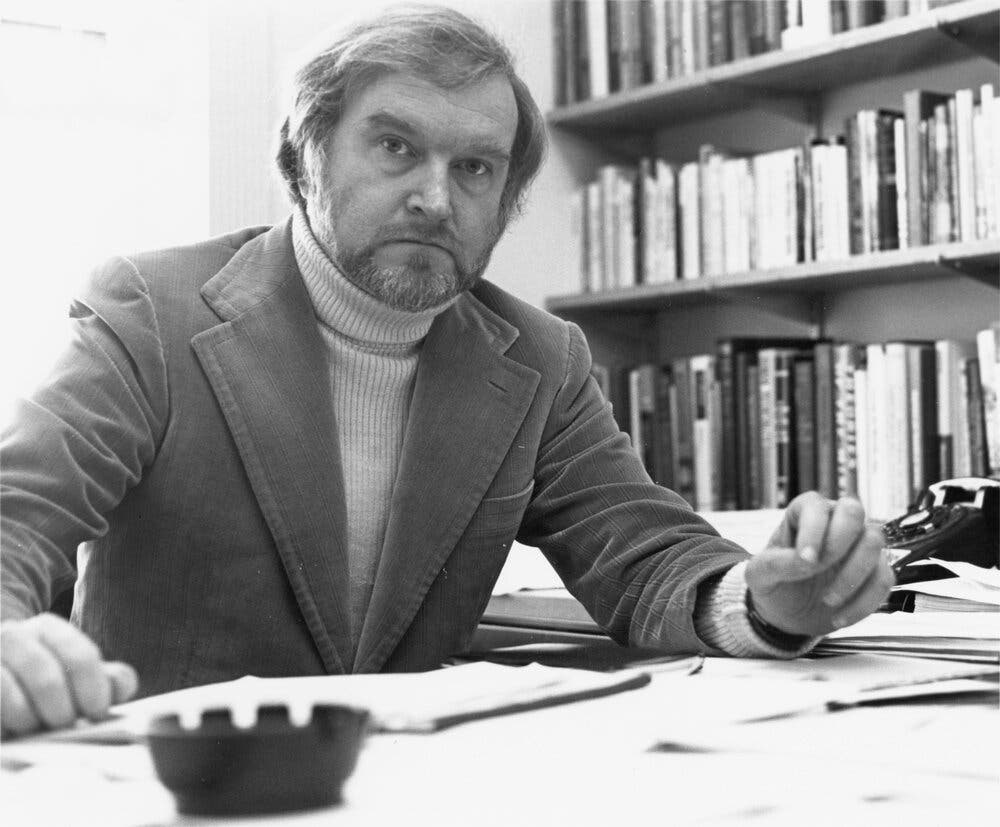

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, the Hungarian-American psychologist who developed the theory of psychological “flow,” passed away recently at age 87. You have probably heard of flow, a concept popularized by his 1990 book of the same name. But there’s much to Csikszentmihalyi’s (pronounced cheek-sent-me-high) ideas about flow that you may not know. Csikszentmihalyi believed that:

- Flow is available to everyone, even in situations we might not normally expect

- Flow isn’t merely a productivity tool, it can be a way to live a more fulfilling life

- Flow isn’t just a state, it’s a way to develop oneself over time

These ideas have greatly influenced our Flow State newsletter. Our moniker “MC” is a nod to him. We wanted to honor the psychologist’s memory by sharing a few of his ideas that influence our work.

Defining Flow

A person in flow is blissfully immersed in a goldilocks activity—something not too hard but not too easy. More technically, flow is the sensation that:

one’s skills are adequate to cope with the challenges at hand, in a goal-directed, rule-bound action system that provides clear clues as to how well one is performing. Self-consciousness disappears, and the sense of time becomes distorted.

When we think about the happiest times in our lives, we often think about states of flow:

- An intense athletic or mental competition

- A really important problem we figured out at work

- An immersive bonding activity with friends or family

Csikszentmihalyi’s achievement was to describe the flow state, trace its roots in the structure of consciousness, and outline the conditions that create it.

Flow is available to anyone

Csikszentmihalyi believed that flow is available to everyone regardless of socioeconomic background or status. You don’t need a glamorous job to access flow. The only things you need are skills (broadly defined) and a goal. It’s possible to flow, for example, during a conversation or while listening to music, as long as you approach it as a challenge requiring skills towards a goal. You can even find it in extreme circumstances:

Essentially the same ingenuity in finding opportunities for mental action and setting goals is reported by survivors of any solitary confinement, from diplomats captured by terrorists, to elderly ladies imprisoned by Chinese communists. Eva Zeisel, the ceramic designer who was imprisoned in Moscow’s Lubyanka prison for over a year by Stalin’s police, kept her sanity by figuring out how she would make a bra out of materials at hand, playing chess against herself in her head, holding imaginary conversations in French, doing gymnastics, and memorizing poems she composed. Alexander Solzhenitsyn describes how one of his fellow prisoners in the Lefortovo jail mapped the world on the floor of the cell, and then imagined himself traveling across Asia and Europe to America, covering a few kilometers each day.

This is obviously a set of extreme examples, but they illustrate one of Csikszentmihalyi’s key points. Access to flow is primarily a function of mindset rather than of external conditions. Of course, we should strive to improve our external conditions, both for ourselves and for others, because they’re inescapable parts of experience. But the other half of the equation is how we approach our experience, which we often have a greater degree of control over.

Flow can help us find fulfillment

The theory of flow isn’t just a productivity toolkit. Csikszentmihalyi believed that understanding flow can help people live more fulfilling lives. On the first page of his book, he explains that the problem he’s trying to solve is widespread dissatisfaction: [1]

Despite the fact that we are now healthier and grow to be older, despite the fact that even the least affluent among us are surrounded by material luxuries undreamed of even a few decades ago (there were few bathrooms in the palace of the Sun King, chairs were rare even in the richest medieval houses, and no Roman emperor could turn on a TV set when he was bored), and regardless of all the stupendous scientific knowledge we can summon at will, people often end up feeling that their lives have been wasted, that instead of being filled with happiness their years were spent in anxiety and boredom.

Csikszentmihalyi conducted a large-scale study on volunteers who carried a device that pinged them multiple times a day to spot-measure enjoyment. Reviewing the data and volunteers’ reflection on their experience, Csikszentmihalyi found that the self-reported “most enjoyable” experiences generally fell under the category of flow. Surprisingly, people reported greater in-moment enjoyment at work than at leisure. The path to happiness, his study concludes, is to design one’s life such that they regularly experience feasible challenges.

But maximizing flow in our lives doesn’t just seem to make us happier; it fundamentally changes us for the better.

Flow isn’t just a state, it’s a way to develop ourselves

Csikszentmihalyi believed that the more one flows the more they cultivate their consciousness:

Following a flow experience, the organization of the self is more complex than it had been before. It is by becoming increasingly complex that the self might be said to grow. Complexity is the result of two broad psychological processes: differentiation and integration. Differentiation implies a movement toward uniqueness, toward separating oneself from others. Integration refers to its opposite: a union with other people, with ideas and entities beyond the self. A complex self is one that succeeds in combining these opposite tendencies.

We believe that you can spot these “complex selves” who spend lots of time in flow. They appear more focused, more present, full of insights and experiences that are personally theirs but universally relevant. Brian Eno, a hero of ours, fits this description. When we watch one of his lectures we detect a distinctly serene and intense attentiveness. The best thing about these “autotelic people,” as Csikszentmihalyi calls them, is that they inspire others to pursue flow states as well.

(There’s of course an important caveat that not all kinds of flow are to be encouraged. For example, a skilled cat-burglar might be totally engaged by the challenge of keeping quiet while stealing jewelry. The question of what goal to pursue is a perennial one and not for this post to answer.)

Designing our work lives for flow

If you buy these ideas about flow (that is available anywhere, that it can lead us to be happier, and that is a way to develop ourselves) then it is worth asking: how can we spend more of our work lives in flow?

For this to happen, Csikszentmihalyi argues, two things are necessary:

On the one hand jobs should be redesigned so that they resemble as closely as possible flow activities – as do hunting, cottage weaving, and surgery. But it will also be necessary to help people develop autotelic personalities...by training them to recognize opportunities for action, to hone their skills, to set reachable goals. Neither one of these strategies is likely to make life much more enjoyable by itself; in combination, they should contribute enormously to optimal experience.

This suggests a two-way responsibility for growing flow at work. Managers and executives ought to structure jobs in ways that help to induce flow. This means clear goals, challenging work, regular feedback, and the freedom to focus. [2] Individuals too, who are looking for more satisfying work lives, can also strive to structure their work with a mindset conducive to flow. It might sound like trite advice—but it isn’t an exhortation to “whistle while you work” so that managers can increase their profit margins.

Instead, we believe it’s a pragmatic recommendation that could help anyone find more fulfillment in their lives, and develop their consciousness more deeply. It applies even to people who on paper have the most enviable jobs around. In fact, it’s easy to become jaded or blasé about a job that’s lovable on paper. Reminding oneself of the importance of a flow mindset is an important safeguard against job dissatisfaction.

Csikszentmihalyi left us with immense wisdom on human flourishing. We encourage you to read Flow for yourself. It will change your life.

Footnotes:

[1] Further, Csikszentmihalyi does a great job of diagnosing a particular kind of rewards framework that has afflicted this author: “A thoroughly socialized person is one who desires only the rewards that others around him have agreed he should long for — rewards often grafted onto genetically programmed desires. He may encounter thousands of potentially fulfilling experiences, but he fails to notice them because they are not the things he desires. What matters is not what he has now, but what he might obtain if he does as others want him to do. Caught in the treadmill of social controls, that person keeps reaching for a prize that always dissolves in his hands.”

[2] In our age of remote work, it should be noted that the self-consciousness aroused by Zoom is anathema to flow: “Preoccupation with the self consumes psychic energy because in everyday life we often feel threatened. Whenever we are threatened we need to bring the image we have of ourselves back into awareness, so we can find out whether or not the threat is serious, and how we should meet it. For instance, if walking down the street I notice some people turning back and looking at me with grins on their faces, the normal thing to do is immediately to start worrying: ‘Is there something wrong? Do I look funny? Is it the way I walk, or is my face smudged?’ Hundreds of times every day we are reminded of the vulnerability of our self. And every time this happens psychic energy is lost trying to restore order to consciousness.”

Find Out What

Comes Next in Tech.

Start your free trial.

New ideas to help you build the future—in your inbox, every day. Trusted by over 75,000 readers.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign in

What's included?

-

Unlimited access to our daily essays by Dan Shipper, Evan Armstrong, and a roster of the best tech writers on the internet

-

Full access to an archive of hundreds of in-depth articles

-

-

Priority access and subscriber-only discounts to courses, events, and more

-

Ad-free experience

-

Access to our Discord community

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!