.png)

Terrain partner Willem Van Lancker wrote our most recent Thesis, about productive friction in the age of AI. Rhea Purohit spoke with him about the origins of his philosophy—including 10 tips for cultivating friction in your own life.—Kate Lee

Was this newsletter forwarded to you? Sign up to get it in your inbox.

Willem Van Lancker was six years old when he learned a lasting life lesson: from a rope, a sail, and the salty taste of a sea breeze.

Van Lancker’s dad, a sailor and boat builder, sent him and his older brother out to sea in a small dinghy. The two boys prepped the boat: tied knots, checked lines, and wrestled sails into place, making sure everything was in place, or so they thought. They’d fixed one of the lines wrong, and as the boat turned into the wind, it capsized. Their father had to swim out and bring them and the boat back to land.

Years later, reflecting on the adventure, Van Lancker recognizes that sailing is as much about preparation as it is about the act itself. What you choose to do, or not do, at that stage is viscerally felt once you’re out on the water. Understanding how all the components go together goes far beyond being a necessary chore; it is essential to making it work at all.

That lesson now drives his contrarian take on AI: As it erodes friction from our lives, we risk losing the struggles that build judgment, expertise, and personal taste. According to Van Lancker, a partner at early-stage investment firm Terrain, a lifelong designer who has worked at Google and Apple, and shepherded several dozen startups from day zero, we need to intentionally preserve friction in our work. We caught up with him to hear about how he’s doing this for himself.

He’s nearly always learned by doing

Van Lancker inherited his love for working with his hands from his parents, his father a boat designer, his mother a painter and an art educator. “In some families, knowledge is passed down through dinner-table debates or the steady drip of books on bedside tables,” he says. “In mine, ideas emerged from busy hands and workbenches crowded with projects.”

Growing up in a house “humming with projects” from an “in-progress car rebuild in the garage” to “printed pillows drying across clotheslines in the yard,” Van Lancker learned by making. “My parents didn’t teach through abstract theories or carefully reasoned arguments; instead, they invited me to join their process and figure it out with them,” he says.

This “hands-on ethos” of learning shaped Van Lancker’s approach well beyond physical crafts, extending to writing, entrepreneurship, and design. “It built into me an appreciation for practice or project-based learning,” he explains, “and an understanding that mastery comes through the slow accumulation of experiments and errors.” In practice, this looks like building scrappy prototypes, iterating quickly, and treating every wrong turn as “necessary friction that deepens expertise.”

Why the cost of convenience is sometimes too steep

Years after learning how to sail as a child, Van Lancker was a designer for Google Maps’s first iPhone app. It was a leap from craft to code, but the thread was the same: finding one’s way. Google Maps, and GPS, changed the way we experience the world around us. The technology is undeniably powerful and convenient, but research suggests that the use of GPS can dull our natural spatial abilities. We become less adept at forming mental maps of our surroundings and intuitively orienting ourselves. Van Lancker acknowledges this tension, noting that in walking the “predetermined path,” we might miss out on the “journey of finding new things.” Serendipity, he believes, is still valuable.

He points to the photo editing features available on smartphones: You tap a button on your screen, and that picture of your dog with a goofy look on their face is suddenly elevated. The image is sharper, the lighting better, the composition subtly improved. Features like this are great for the average iPhone user, but if you want to be a professional photographer, you might end up losing some intuitive sense of how to take good photos. “It abstracts a lot of the conceptual thinking away,” Van Lancker says.

When it comes to design, he says that indiscriminate or thoughtless use of AI tools can “atrophy your ability to create a foundation of your own.” The tool inevitably primes you to think a certain way—and without a chance to discover the direction you would’ve gone absent the tool, you risk losing your own style.

How to create your own friction

This pattern isn’t new: Technology has long simplified complex processes and changed the way we create. The challenge—and opportunity—is to have a point of view rooted in a deep understanding of the context behind what you make. “The best way to differentiate yourself and push the goalpost forward,” he says, “is to have a sense of what got you there and then build on that in a way only you can.”

A few of the things Van Lancker does to cultivate friction in his life:

- He avoids auto-scheduling tools, believing that manually coordinating meetings preserves his intentionality and responsibility over his time. This intentional friction prompts deeper consideration of each meeting's purpose and value, ultimately leading to fewer meetings and more focus within each.

- When working with portfolio companies, he opts for hands-on involvement. This approach establishes trust and partnership with founders, providing firsthand insights essential for offering feedback. He counters the stereotype of passive investors: “There is a meme of VCs not being able to be helpful. The way I see it, that makes sense. They’re armchair quarterbacks. I’ve unlocked a lot by getting into it with the founders, even if it's just for a few hours.”

- He often turns to analog methods of early creation, like sketching on paper or handwriting notes, instead of immediately resorting to digital tools. The slower pace offers deeper focus and naturally restricts the ideas to their simplest.

- In creative visual work involving AI, he prefers using MidJourney over more structured tools like ChatGPT’s image generation for creative visual work involving AI. MidJourney can be more chaotic to use, but he embraces its inherent chaos, valuing the greater control and creative freedom it provides in shaping the final product.

- To avoid impulsively “just shipping it,” he introduces deliberate friction through cooldown periods when reviewing designs or providing feedback. This intentional pause allows ideas to mature, fostering more thoughtful and meaningful responses.

- When conducting research, he prioritizes curiosity over canonical paths, often taking unconventional routes through the work. Though this approach can lead to roundabout explorations, he believes starting where genuine interest lies ultimately reveals the most critical insights.

- He tries to focus or limit sources of “frictionless consumption,” though he’s not an absolutist: “That kind of stuff has a time and place, particularly if you’re stuck on a problem. Sometimes, procrastinating on something simple or distracting can allow the right thought to appear. You move it to the back of your mind, and where it has a bit more freedom to arrive.”

- He incorporates physically demanding work into regular life to get out of the headspace and “above the shoulders” world of software and the internet, and engage other practical senses and skills (gardening, woodworking, repairs) that ground you in the present.

- He leaves room for spontaneity and problem-solving by introducing strategic uncertainty, planning projects or acting on ideas without detailed itineraries: “Committing to things beyond your comfort zone is the only way to build adaptability and resilience.”

- He encourages questioning what you read and taking the other side, even if you (or anyone you are around) doesn’t believe it. This isn’t to be contrarian for the sake of it but instead to push yourself into a friction-filled point of view outside of the bubble you may be in.

Less gear, more clarity

Van Lancker is a minimalist when it comes to his work setup. “I’ve never invested in a desk setup, big displays, or anything like that,” he says. “Right now, the only intentional part of my workspace, that you might see behind me if we’re on a call, is a massive landscape painting, a gift from my mom.”

To outline an idea, he grabs whichever notepad or journal happens to be closest. He likes writing with Sharpies because of the “fidelity” of thought they bring. He says they force a “simpler way of writing.”

That same simplicity carries over to his desk. Van Lancker props his laptop up on a three-volume book about the design of keyboard and typewriters, Shift Happens by designer Marcin Wichary. “It is a really special book and a great example of obsessive depth in design but also the perfect height for a laptop stand,” he says.

Van Lancker’s approach to work is a reminder that not everything needs to be fast and easy. Friction, after all, is what gives us grip. And sometimes, the harder way is the better one.

Rhea Purohit is a contributing writer for Every focused on research-driven storytelling in tech. You can follow her on X at @RheaPurohit1 and on LinkedIn, and Every on X at @every and on LinkedIn.

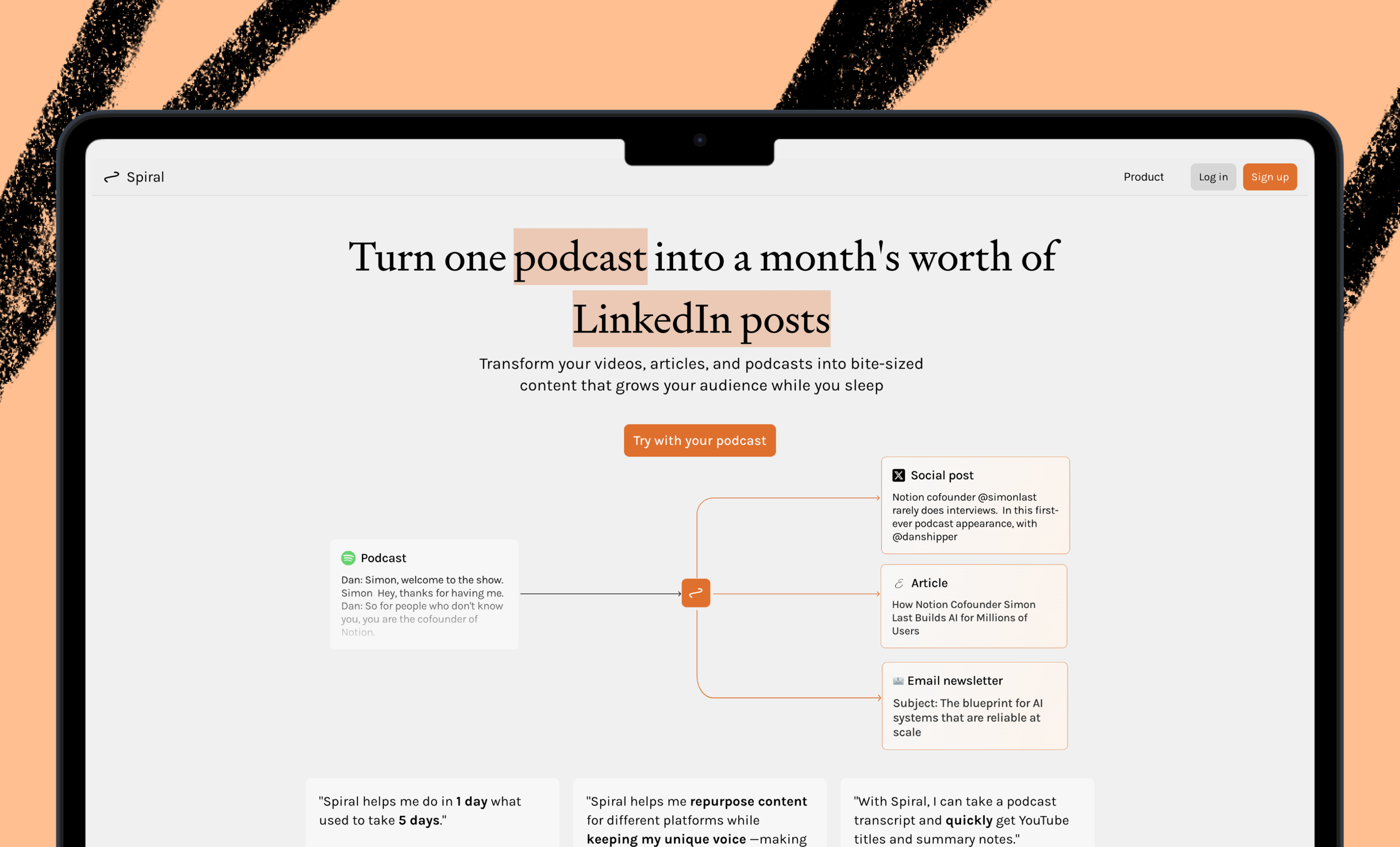

We build AI tools for readers like you. Automate repeat writing with Spiral. Organize files automatically with Sparkle. Deliver yourself from email with Cora.

We also do AI training, adoption, and innovation for companies. Work with us to bring AI into your organization.

Get paid for sharing Every with your friends. Join our referral program.

Ideas and Apps to

Thrive in the AI Age

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!