Sponsor Every

Want to reach AI early-adopters? Every is the premier place for 80,000+ founders, operators, and investors to read about business, AI, and personal development.

We're currently accepting sponsors for Q3! If you're interested in reaching our audience, learn more:

When Jose Briones immigrated to the United States in 2010 at age 15, he was met with a technological shock. In Nicaragua, where he was born, smartphones had yet to become widespread. They were expensive luxury items or reserved for emergencies, with minutes purchased in advance to make phone calls. His childhood was largely spent offline. In America, he got his first smartphone—a Huawei device with unlimited talk, text, and data—and relished the freedom to quickly look up soccer scores, listen to music on Pandora, and access information in seconds.

But as he moved from adolescence to adulthood, his enthusiasm for technology turned to obligation, then oppression. Throughout his years in college and in the working world, he felt tethered to his devices and stuck to a screen. Distraction plagued his waking hours, resulting in a painful period of procrastination while obtaining his Master’s degree. In 2019, he decided he needed a break—the notifications, the constant texting, the binging of TV shows and social media and news—and made a change. Today, Briones has relinquished his smartphone outside of working hours, and is an advocate and evangelist for digital minimalism.

He’s not alone. Briones is part of a growing movement of people who believe we benefit as individuals and a collective by unplugging from internet-enabled technology. “People are tired of feeling a lack of control over their lives. It physically makes a difference in our lives when we are tethered, in our eyesight and the way we feel,” says Briones. “Especially knowledge workers, you're in front of a computer all day. You're sitting down. There's no movement [or] physical engagement with anything.”

A 2021 survey from Pew Research Center found that 31% of U.S. adults report they are online “almost constantly.” U.S. teenagers age 13-17, similarly, feel a stronger pull to be online—in another 2022 survey from Pew Research Center, nearly half of teens say they use the internet “almost constantly,” 36% say they spend “too much” time on social media, with 54% of teens admitting it would be hard to give up social media. Excessive internet use has led to a slew of proposed solutions—digital detoxes and disconnection retreats, 24-hour tech relief in the form of a (somewhat dubious) “digital Shabbat,” and 12-step programs for internet and technology addiction. Boot camps intended to rehabilitate the internet-addicted have been around since the aughts.

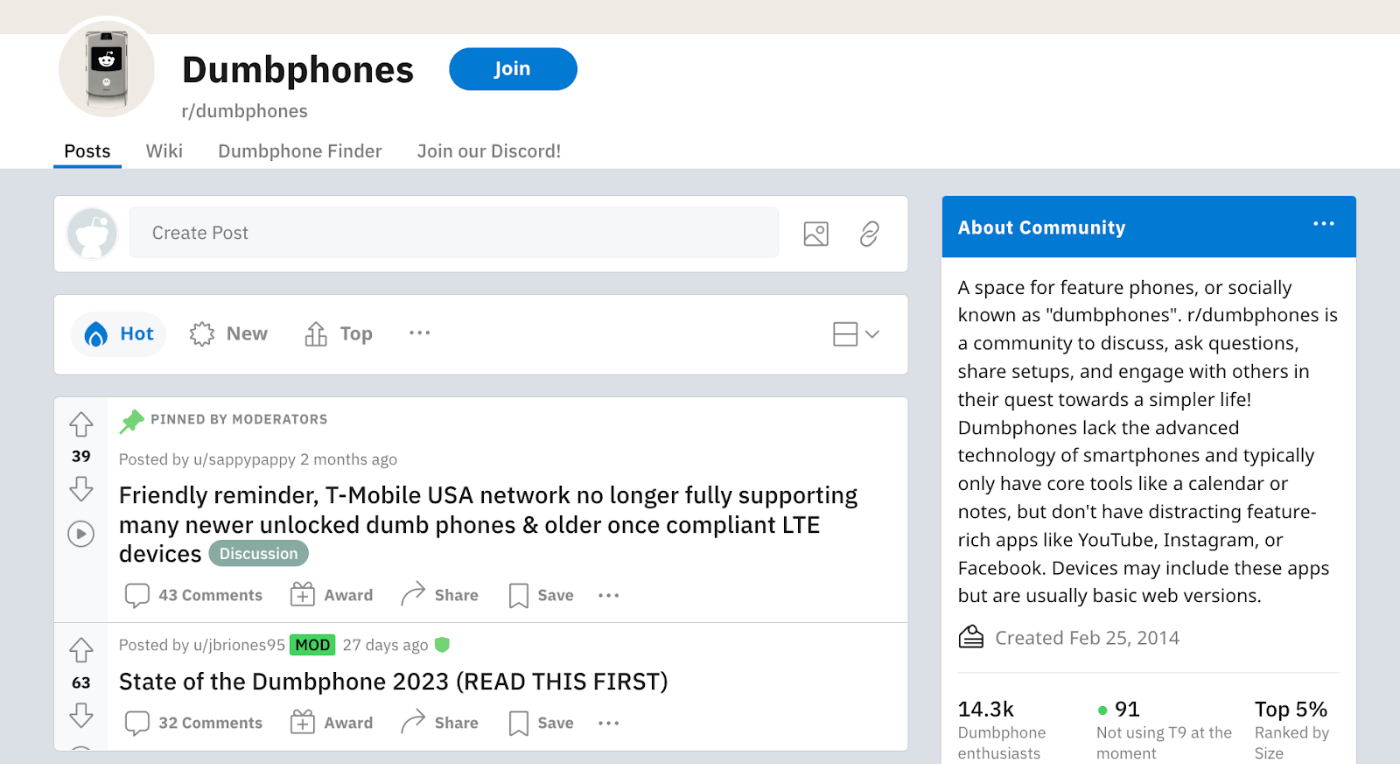

The “why” behind excessive internet use—from social isolation to addictive algorithms—varies depending on who you ask. But some see a clear culprit for our distraction-prone era: the smartphone. This is the case for over 14,000 Reddit users in r/dumbphones, a subreddit in the top 5% of communities on the platform. Briones, a dumbphone user himself, is one of the community’s moderators and also runs the website Dumbphone Finder. He suggests that making a transition to a dumphone—simple talk-and-text devices—is challenging, but ultimately worthwhile. “Learning to live an ‘inconvenient life’ is difficult,” says Briones. “In the beginning, there's a lot of friction, but it's rewarding if you adapt it to your lifestyle.”

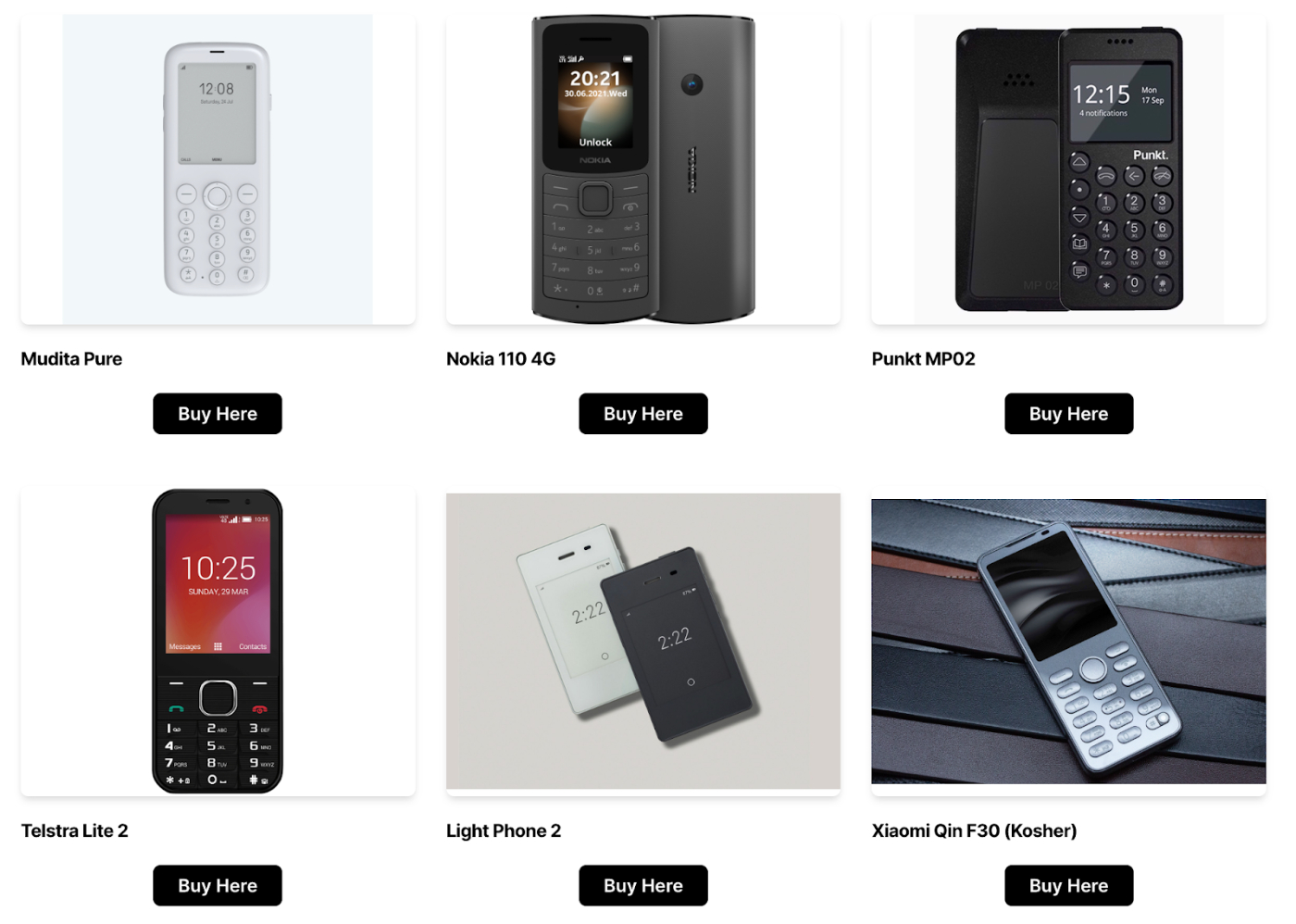

Many of the community's members are keen to take on the challenge, giving up smartphones they feel are a gateway to distraction and addiction. The community defines dumbphones as devices that “lack the advanced technology of smartphones” and note that they lack “distracting feature-rich apps like YouTube, Instagram, or Facebook.” Some opt for flip phones with tiny screens and buttons instead of touch screens, like the Nokia 3310, while others explore a new breed of minimalist devices like the Light Phone II. The aim of the community is clear: “the quest towards a simpler life.”

Swapping smartphones for ‘dumbphones’

Long gone are the days of mainstream talk-and-text devices and paying for minutes. For nearly 20 years, the phone industry has been on a mission to fit the most advanced computer into pocket-sized machinery. The last Apple event in September 2022 saw the release of the iPhone 14 Plus, touted as its “most innovative lineup yet” with features like Always-On display (keep your home screen dimmed but accessible while locked), Cinematic 4K24 (automatic focal point switching while shooting video), and a Photonic Engine (a technology to enhance low-light photos)—not to mention 1.8 million apps at your fingertips. But those on r/dumbphones are seeking out another kind of experience entirely: a phone that does next to nothing.

According to the subreddit’s analytics, r/dumbphones saw 408,587 page views (14.1% of which were unique) and gained 971 members in November 2022 alone. Some members are digital minimalists, some are privacy enthusiasts, some enjoy the aesthetic of a minimalist phone, and some are “self-diagnosed internet addict[s].” All are on the quest for a quieter phone experience free from the pull of algorithmic feeds. Browse through the conversations and you’ll find users sharing their experiences with phones like the Alcatel Go Flip or the Nokia 8110. Others ask for advice on maintaining a dumbphone for life but a smartphone for work—needing the advanced security features like two-factor authentication and work apps like a calendar to perform their roles on the latter.

The ethos of the community isn’t anti-tech, but tech-critical. The smartphone is viewed as a rabbit hole leading towards hours of scrolling; some discuss the “constant IV stream of social media” as their motivation for making the switch. For years we’ve had options to make the smartphone less distracting: switch to grayscale, turn off notifications, use an app blocker. But these solutions are meant to affect your habits, not your lifestyle. For the r/dumbphones community, a simpler life requires a simpler phone. Disconnection isn’t within reach if you still have unmitigated access to a bright phone with dark UX patterns that aim to keep us hooked.

When Ashton Womack, an online creator and the entrepreneur behind the stationary brand Virgo and Paper, watched the 2020 Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma, she resolved to change her relationship to technology. A business owner, she had felt compelled to use Instagram as a growth tool, to connect to customers and promote her work. It took around six months for her to decide on switching to a dumbphone—a simple Nokia 225 flip phone. She reflected on the year-long experiment in a series of YouTube videos, including a Q&A on her year without a smartphone and a discussion on lessons learned.

It wasn’t until after the experiment that Womack realized how attached to her phone she had been. Before a Nokia flip phone replaced her iPhone, she was spending countless hours online, losing presence in the world outside her device. Her ability to get from place to place was limited, because she had relied on the GPS on her smartphone for directions. “I didn't think at that time that I had a smartphone addiction, or that I was spending too much time on my phone. But after going without it for a year, I realized maybe I actually really do have a dependency on it,” said Womack to me over Zoom. “I was spending a lot of time on it back then. But at the time, it seemed normal, because everyone else is doing the same exact thing.”

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!