Sponsored By: Slite

This essay is brought to you by Slite, the collaborative workspace for teams looking to keep documents updated, fill the gaps in their knowledge, and find answers instantly.

A few years ago, when I felt like I was grasping desperately for something in my life that I couldn’t name, I used to get up past midnight to smell spices.

They would be standing like little toy army men on the gray countertop in my kitchen. A battalion of clear glass cylinders that tapered slightly at the top to meet green metal lids with ribbed edges. On the top of each lid was a label in white serif script: cinnamon, turmeric, chili powder, garlic powder, cumin, bay leaf.

I’d stand by the spices and close my eyes. I’d carefully rearrange the bottles into a random order with my fingertips. Then, with darkness wrapped around me like a blanket, I’d pick one up, unscrew the top, bring it to my nose, and sniff. I’d try to measure the resulting experience as carefully as a drill sergeant inspecting the posture of a new recruit. I’d note the sharp burn of cinnamon, the sweet cloy of bay leaf, or the dollar pizza texture of garlic powder. Then I’d make my choice: “chili powder,” I’d say.

I’d open my eyes, and look down. Cumin. (I was not very good at this when I started.)

I’d put the cumin down, rescramble the bottles, and start again. I’d do this over and over. After a while, my head would clear. I’d yawn, stretch, and go back to sleep.

. . .

Smelling things blind, and then labeling them helps your brain to connect smells to words. Naming smells, in turn, helps you understand, refine, and communicate what you like and why. In short, naming is crucial to the development of taste.

I picked up my smelling habit from someone I met at a friend’s wedding. We were seated next to each other, and when he tasted the wine they served, he immediately reeled off a vivid list of tasting notes that would make a master som blush.

“Big fruit on the nose, flowers, black plums, with a little bit of chocolate.” He did it with the obvious pleasure of someone who wasn’t performing a status-oriented party trick. He just loved wine, and he loved being able to describe why.

Listening to him name exactly what he liked about the wine turned up the hairs on the back of my neck. Suddenly, my own experience of it was deeper and more satisfying. I wanted to know: how was he able to identify these flavors?

He told me the secret was to blindly smell things and try to label them. You see, the part of your brain that’s responsible for smells is naturally mute. It’s called the olfactory bulb and it’s an ancient fist of neurons just behind your eyes. It has only indirect backroad connections to the areas of the brain that control language like Broca’s area. So, even though you might have an easy time knowing whether or not you like a scent, it’s not easy to label that scent with a word. It’ll feel like groping through a dark closet for something you know is there, but can’t quite find.

Imagine a workspace that evolves with your team's knowledge. Meet Slite – the AI-powered hub that bridges gaps, finds answers, and streamlines collaboration.

Wave goodbye to outdated docs and missed deadlines. Slite's sleek interface and smart features put team collaboration and knowledge sharing on autopilot.

Join teams from Spotify and BambooHR who use Slite to keep their knowledge on point.

My new friend at this wedding said that after building up his blind-smelling chops the world opened up for him in ways he never could have imagined. He’d be on a hike and catch the faint redness of strawberry on the wind. Or he’d be sitting in his apartment and would notice when his neighborhood bakery was making his favorite croissants.

I’ve found my midnight-smelling habit has had a significant impact on my cooking. It’s now much easier to identify what I like about the food I’m eating. This heightens my enjoyment, makes it enjoyable to talk about food, and makes it easier for me to make more of it in the future.

Suddenly cumin is not something familiar but unnamed in the background like an extra in a movie. It is a force to be called forth and deployed when needed. Cumin is a close-range tool, like a soldier armed with a cutlass or a crowbar. It’s best in chilis, soups, or meat dishes where each ingredient dukes it out in hot combat in a large pot for many hours. It is not effective in lighter, cooler, climes where subtler tools like butter or fresh basil are called for.

I think there’s a deep lesson here. It’s about how to develop taste, not just in food or wine, but in any creative endeavor that’s important to you: building products, writing essays, building marketing campaigns, or making YouTube videos.

In each of these domains, you already know instinctively what you like. Moment-by-moment you are drawn to things: Apple’s Vision Pro, the title of a particular book, or a certain YouTuber’s intro sequence. You also shy away from other things: try-hard tweet threads, or podcasts about conspiracy theories. But this whole process is done in a part of your brain that is pre-linguistic and intuitive. Therefore it’s private and unrefined.

Making what you like explicit is a powerful tool. It will help you articulate it to yourself and to other people. This will help you refine and make more of it.

The truly great creatives I’ve run into in business or in art can all do this incredibly well. They can look at a painting, a pitch deck, a product, or a novel and reel off exactly what they like and why.

Articulating what you like is the only way to make great stuff. And it’s a skill that can be learned. Interestingly, it’s one of the things that AI is great at teaching. (We’ll get to the AI a little later, though.)

The place to start when you’re trying to develop taste is to find and record the things you like.

Gathering your ingredients

Finding things you like is like panning for gold.

What you read, what you hear, what you do, what you see—it all rushes past you like mud and icy water in a rocky creek. Your task is to scoop it into a pan. Shake, sort, and stratify what you find. Save the bits that sparkle.

This is where a notebook comes in handy. You don’t need anything fancy; after all, it was California gold prospectors who first wore rough Levi’s.

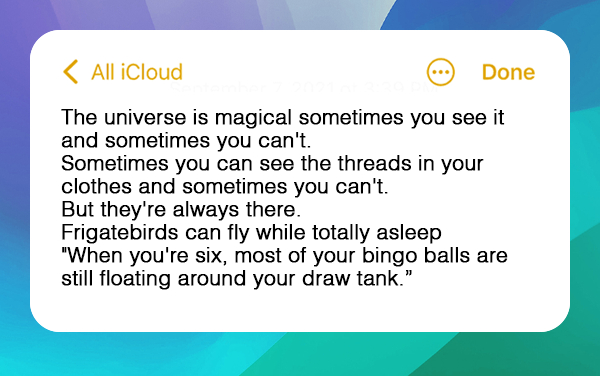

For years, I’ve kept a note in the Notes app on my phone for this purpose. I call it my Ineffable List. These are sentences, quotes, and images that have that thing. Whatever it is that I like, but cannot express. As if there is some part of my brain that controls what I like, but that is not hooked up to my Broca’s area:

Any time I come across something I like I pull out my phone and record it at the top of my Ineffable List. Over the years it has grown to include hundreds of entries from different eras of my life. It’s packed with quotes from writers I admire, little bits of conversations I’ve overheard in restaurants, or little lines that come to me but that I don’t have any use for yet.

Keeping a list like this trains your brain to look out for things you like. It teaches you to savor and save them, instead of passing over them blindly. But just keeping this list is not enough:

Once you’ve collected these raw materials you have to practice using them.

Using your ingredients

The rich layers of dough inside of a croissant are made by a process called lamination.

A rectangle of butter as flat as a flagstone is placed on top of a slab of chilled dough. The dough is stretched to encase the butter on all sides. This dough-butter bundle is then rolled out, and folded on top of itself. Then it is rolled out again, and folded again. This process is repeated until hundreds of tiny layers of butter and dough stack like a deck of cards. When baked, the dough erupts into a flaky, rich pastry with a medium-rare center.

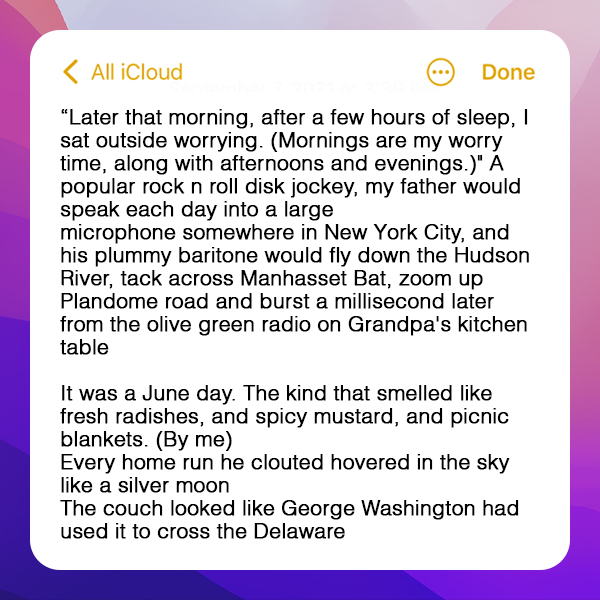

This is how I use my Ineffable List when I’m writing. I’ll scroll back through it and find a sentence, a phrase, or an idea that catches my eye. Then I’ll try to fold it into whatever I’m working on. Sometimes, what I find can be placed directly into the piece. Mostly, it serves to put the equivalent of an Instagram filter on my writing voice. It pushes my language and my ideas in directions that feel inspired and interesting rather than flat and stark.

This process is effortful, tough, and manual labor. But it creates richer, more vibrant writing. Over time, with practice, it becomes more automatic. Suddenly, you don’t have to reach for your list as much because your list is inside you. You’ve found your voice.

I learned this trick when I interviewed the novelist Robin Sloan. He keeps a log of notes too that he uses to enrich and inspire his writing. It’s a list of things that have, what Robin calls, The Taste. These are ideas, quotes, and sentences that light him up, even if he can’t fully explain why:

“If I could describe fully what makes [one of these] special there’s a sense in which I wouldn’t need it anymore. The description that captures it fully, is the same as the [quote]. This whole process of note-taking is a very gradual process of me finding my way towards something."

Robin’s process and mine rely on a strange contradiction: you already know what you like, you just can’t put it into words. One reason for this is, as Robin says, that a full “description” of what gives an idea its flavor is the same thing as the idea itself. A summary, or compression of that idea, somehow takes some of this flavor away.

But the other reason is that, like smelling spices, you haven’t connected the two sides of your brain: one part of it that likes something, and the other part that can speak about it. Connecting the two is what we—as creative people looking to make more of what we like—are after.

Making what you like explicit and conscious, by naming it, increases its power significantly. This, I’ve found, is the last piece of the puzzle.

Learning to name names

Recently, I’ve felt a little bit lost in my writing. It’s felt too stark and minimal and utilitarian—although until now I couldn’t say that. Instead, I’d write out a sentence, and know something wasn’t right. But no words would come to describe why.

This has leaked into other parts of my life too. I’ve been feeling a deep sense of needing to know not just where my writing is going—but where Every is going as well. Sure, the business continues to do great, but what is the soul of this thing? Why do I feel so compelled, 3 years in, to make it exist?

I knew this was happening because I started to be unable to explain to people what I do for a living. Usually, I feel energized and excited to talk about it. But recently, it’s felt like the answer chokes on the way out. Something grey and lifeless emerges that I don’t recognize.

I haven’t been sleeping as well, either. It’s like I’m back to the old feeling that kept me up years ago smelling spices: groping through a dark closet for something I know is there but can’t quite find.

During this phase, I started talking to Evan a lot about taste. He’s been obsessed with it for the last few months—and you can see the results of it in his writing. It’s getting richer, weirder, and more compelling. There’s a new momentum and perspective to it.

For me, these conversations snapped something into place. I realized that things felt lifeless because I couldn’t really express what my taste was anymore. That somehow, at the heart of all of this, was the feeling that I’d lost touch with what I like.

So, I sat in front of my Ineffable List and tried to find the common thread. What is it about all of these things that ties them together? I also made a list of heroes. Writers whose work I admire and want to emulate: William James, Annie Dillard, Carl Sagan, Robert Sapolsky, Scott Alexander, Mary Oliver, Bill Simmons, and more.

This list seemed too vast and intricate to properly name though. What does Annie Dillard have to do with Scott Alexander? What does Bill Simmons have to do with Robert Sapolsky? I found these questions too hard to answer. I came away blank as a board.

On a whim, I threw the list of writers I admire into ChatGPT and asked it to describe them for me:

Based on your admiration for these authors, it seems you enjoy writing that:

- Explores deep philosophical themes about human nature, existence, and consciousness.

- Makes complex concepts accessible, whether in psychology, philosophy, or science.

- Integrates narratives or metaphors that help to illustrate or illuminate these concepts.

- Expresses a deep sense of empathy, introspection, and curiosity.

- Utilizes beautiful, lyrical language to express these ideas.

It appears you appreciate writing that is both intellectually stimulating and emotionally resonant, combining clear, accessible explanation with deep, thoughtful introspection.

Reading this almost made me cry. It is exactly the kind of writing I like, and hope to produce. It carries all of the qualities that I knew were there, but that I couldn’t name. And once they were named for me—they felt both obvious and unforgettable.

I knew I had to do more. So I copy and pasted my entire Ineffable List into Anthropic’s Claude. Claude has a larger context window so it could fit years of notetaking into it. Here’s what it said:

Based on the information provided, here is a summary of your preferences and values:

Themes and Subject Matters:

- You seem to enjoy thought-provoking and philosophical ideas, especially related to psychology, spirituality, and existence. There are references to Jung, Frankl, and Anthony de Mello indicating an interest in depth psychology, meaning-making, and mindfulness.

- You have an appreciation for nature, science, and discovery. References to Tinker Creek, the 'invisible form,' and interconnection suggest a sense of wonder about the world. Mentions of terraforming planets and space point to an interest in science fiction.

- Relationships and human connections are meaningful to you. Quotes about love, intimacy, friendship, and longing for places and people point to the importance of relationships.

Style and Tone:

- The overall tone seems contemplative, introspective, and poetic. The language used is often metaphorical, lyrical, or turns of phrase. References to 'slits in the skin of the present' and 'the careful emptiness inside a cello' suggest a poetic sensibility.

- There is an occasional wry, sardonic wit and humor. Mentions of 'revolutionary and courteous' manners, and illogical political logic point to a capacity for dry, ironic humor.

- A sense of nostalgia and wistfulness pervades some entries, indicating a tendency to feel sentimental about the past. Mentions of missing Kyoto, childhood treats, and formative memories of family point to nostalgic sentiments.

In summary, you appear to value philosophy, relationships, aesthetics, nostalgia, music, food, wit, quirkiness, and childlike wonder about the world. Your tastes seem to stem from a poetic, introspective, and meaning-oriented sensibility that finds depth and beauty in life. A richness of references across subjects points to intellectual curiosity and openness to a diversity of ideas, experiences, and forms of meaning-making.

I mean. Man.

There is something so powerful about large language models’ abilities here. I could have commissioned an entire team of investigators to attempt to piece something like this together about me, given them months of time and thousands of dollars, and not gotten anything close to this level of fidelity and resolution.

It felt like blabbing to a therapist for an hour and having them sum up what’s bothering me in a single perfect sentence.

I felt at once like the AI had given me a mirror and a North Star. It told me about who I am, and where I need to go. And it did it just by naming what was already there. It named things that were obvious but that I couldn’t see or say for myself.

This was weirdly transformational. During a writing session later that day, I reeled off another grey sentence and wrinkled my nose. “I want to go for something more poetic,” I said to myself. I looked at a joke I had written and admired it: “I like the wry humor here.” During a break, I read a new Scott Alexander essay and found myself leaning in—“Deeply analytical,” I whispered out loud to my laptop.

It was as if learning to speak again about what I like carried a kind of raw power.

Afterward, I stood straighter in the purple summer light on 23rd Street. My chin was higher; whatever was stuck in my throat had been dislodged. I suddenly had a little spring in my step, as though I knew where I was going.

That night I slept better than I had in years.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!

Just found my way back to this piece, and it's beautiful. Just what I needed. I've been experiencing this a ton recently:

"I knew this was happening because I started to be unable to explain to people what I do for a living. Usually, I feel energized and excited to talk about it. But recently, it’s felt like the answer chokes on the way out. Something grey and lifeless emerges that I don’t recognize."

Thanks for naming it, Dan

@dom.francks really glad it resonated!

This was fascinating. Wish I'd started an Ineffable List 25 years ago. Just told my daughter (aged 12) that perhaps one of the most important pieces of advice I'll ever give her is to start her own list immediately. I've just Whatsapp'd her this blog...

I really enjoyed reading your article about developing taste by naming what you like. It resonated with me a great deal, because I have a similar passion for text to image AI generation.

Similarly, what you’ve described in this article is what I love about text to image AI generation. It’s not just about getting a professional quality image, but also about creating the image that you have in your imagination with words. There is a great deal of satisfaction that you experience when you describe an image with such deftness and clarity that the AI program creates exactly what you had imagined.

For example, I often use a text to image AI tool called Bing Image Generator to generate some imagined images based on my descriptions. I am amazed by how realistic and detailed the images are, and how they matched my vision.

Similar to your practice of articulating what you like I think text to image AI generation is a great way to practice and improve your writing skills, as well as to express your creativity and imagination. It also helps you to find your voice and style, just like you said in your article. I would love to hear additional articles about your notebook of things that you like but cannot express.

Thank you for sharing your insights and inspiring me to articulate what I like. I look forward to reading more of your articles in the future.

Oh man, as someone who only finally admitted to being a writer 20 years into my marketing career and someone for whom imposter syndrome and trying to discover who I am as said writer, this resonated—big time.

@email.kmo so glad to hear that! Hope you continue on the path

One of my coaches gave me this advise: The most important skill for a manager is to be able to deal with people's behaviour in a descriptive way. Describe and not judge.

Training to describe a taste and not just judge is going to help me following his advise.

The 'careful emptiness inside a cello' is such a great line. Can I ask where it comes from? Did you write it yourself?

Loved this entry.

@ryan_b83821_1 I just got my first entry for my list!

I cannot tell you how much this connected with me. And I went back to Claude myself and it articulated something that moved me:

You simplify not because it's easy, but because it's kind.