Sponsored By: Mindsera

This article is brought to you by Mindsera, an AI-powered journal that gives you personalized mentorship and feedback for improving your mindset, cognitive skills, mental health, and fitness.

How hard should I optimize? It’s a question I’ve often asked myself, and I bet you have too. If you’re optimizing for a goal—building a generational company, or finding the perfect life partner, or devising a flawless workout routine—the tendency is to try to go all the way.

Optimization is the pursuit of perfection—and we optimize for our goals because we don’t want to settle. But is it better to go all the way? In other words, how much optimizing is too much?

. . .

People have been trying to figure out how hard to optimize for a long time. You can put them on a spectrum.

On one side is John Mayer, who thinks less is more. In definitely-his-best-song, “Gravity,” he sings:

“Oh, twice as much ain't twice as good / And can't sustain like one half could / It's wanting more that's gonna send me to my knees.”

Dolly Parton, who seriously disagrees, is on the opposite side. She’s famous for saying, “Less is not more. More is more.”

Aristotle disagreed with both of them. He propounded the golden mean 2,000 years ago: when you’re optimizing against a goal, you want the middle between too much and too little.

Which one do we pick? Well, it’s 2023. We want to be a little more quantitative and a little less aphoristic about this. Ideally, we’d have some way to measure how well optimizing against a goal works out.

As is the case very often these days, we can turn to the machines for help. Goal optimization is one of the key things that machine learning and AI researchers study. In order to get a neural network to do anything useful, you have to give it a goal and try to make it better at achieving that goal. The answers that computer scientists have found in the context of neural networks can teach us a lot about optimizing in general.

I was particularly excited by a recent article by machine learning researcher Jascha Sohl-Dickstein who argues the following:

Machine learning teaches us that too much optimization against a goal makes things go horribly wrong—and you can see it in a quantitative way. When machine learning algorithms over-optimize for a goal, they tend to lose sight of the big picture, leading to what researchers call “overfitting.” In practical terms, when we overly focus on perfecting a certain process or task, we become excessively tailored to the task at hand, and unable to handle variations or new challenges effectively.

So, when it comes to optimization—more is not, in fact, more. Take that, Dolly Parton.

This piece is my attempt to summarize Jachsa’s article and explain his point in accessible language. To understand it, let’s examine how training a machine learning model works.

Mindsera uses AI to help you uncover hidden thought patterns, reveal the blindspots in thinking, and understand yourself better.

You can structure your thinking with journaling templates based on useful frameworks and mental models to make better decisions, improve your wellbeing, and be more productive.

Mindsera AI mentors imitate the minds of intellectual giants like Marcus Aurelius and Socrates, offering you new pathways for insight.

The smart analysis generates an original artwork based on your writing, measures your emotional state, reflects on your personality, and gives personalized suggestions to help you improve.

Build self-awareness, get clarity of thought, and succeed in an increasingly uncertain world.

Too much efficiency makes everything worse

Say you want to create a machine-learning model that’s excellent at classifying images of dogs. You want to give it a dog image and get back the breed of dog. But you don’t just want any old dog image classifier. You want the best machine learning classifier money, code, and coffee can buy. (We’re optimizing, after all.)

How do you do this? There are several approaches, but you’ll probably want to use supervised learning. Supervised learning is like having a tutor for your machine learning model: it involves quizzing the model with questions and correcting it when it makes mistakes. It’ll learn to get good at answering the types of questions it’s encountered during its training process.

First, you construct a data set of images that you use to train your model. You pre-label all of the images: “poodle,” “cockapoo,” “Dandie Dinmont Terrier.” You feed the images and their labels to the model, and the model begins to learn from them.

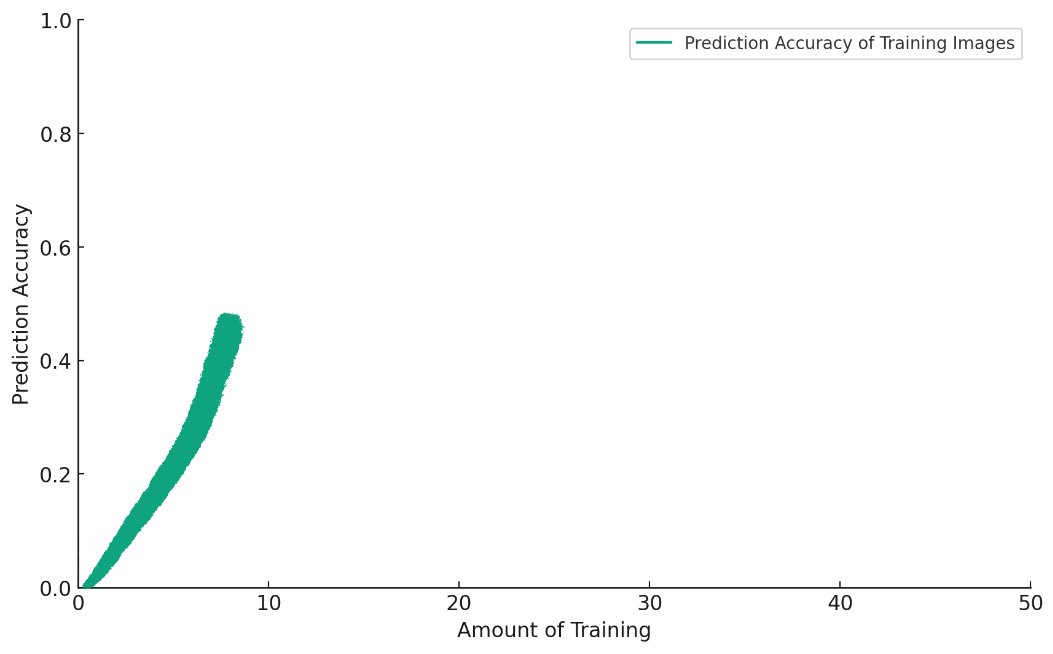

The model learns by a guess-and-check method. You feed it an image, and it guesses what the label is. If it gives the wrong answer, you change the model slightly so that it gives a better one. If you follow this process over time, the model will get better and better at predicting the labels to images in its training set:

Now that the model is getting good at predicting the labels for images in its training set, you set a new task for it. You ask the model to label new images of dogs that it hasn’t seen before in training.This is an important test: if you only ask the model about images it’s seen before, it’s sort of like letting it cheat on a test. So you go out and get some more dog images that you’re sure the model hasn’t seen.

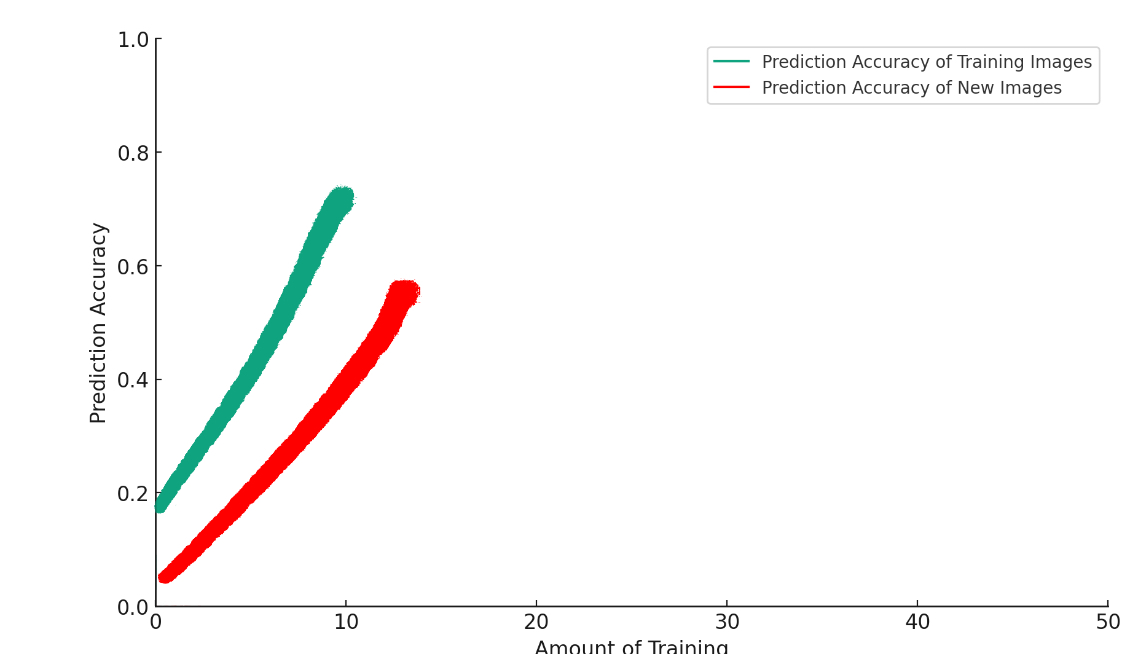

At first, everything is very rock and roll. The more you train the model, the better it gets:

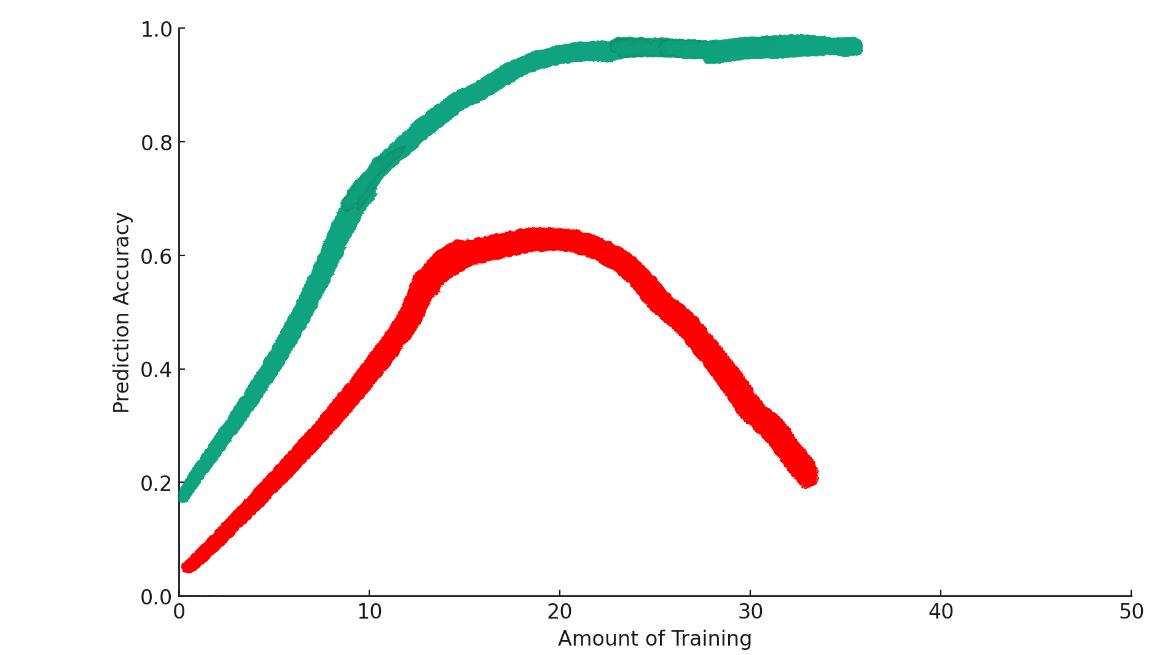

But if you keep training, the model will start to do the AI equivalent of shitting on the rug:What’s happening here?Some training makes the model better at optimizing for the goal. But past a certain point, more training actually makes things worse. This is a phenomenon in machine learning called “overfitting.”

Why overfitting makes things worse

We’ve been doing something subtle with our model training.

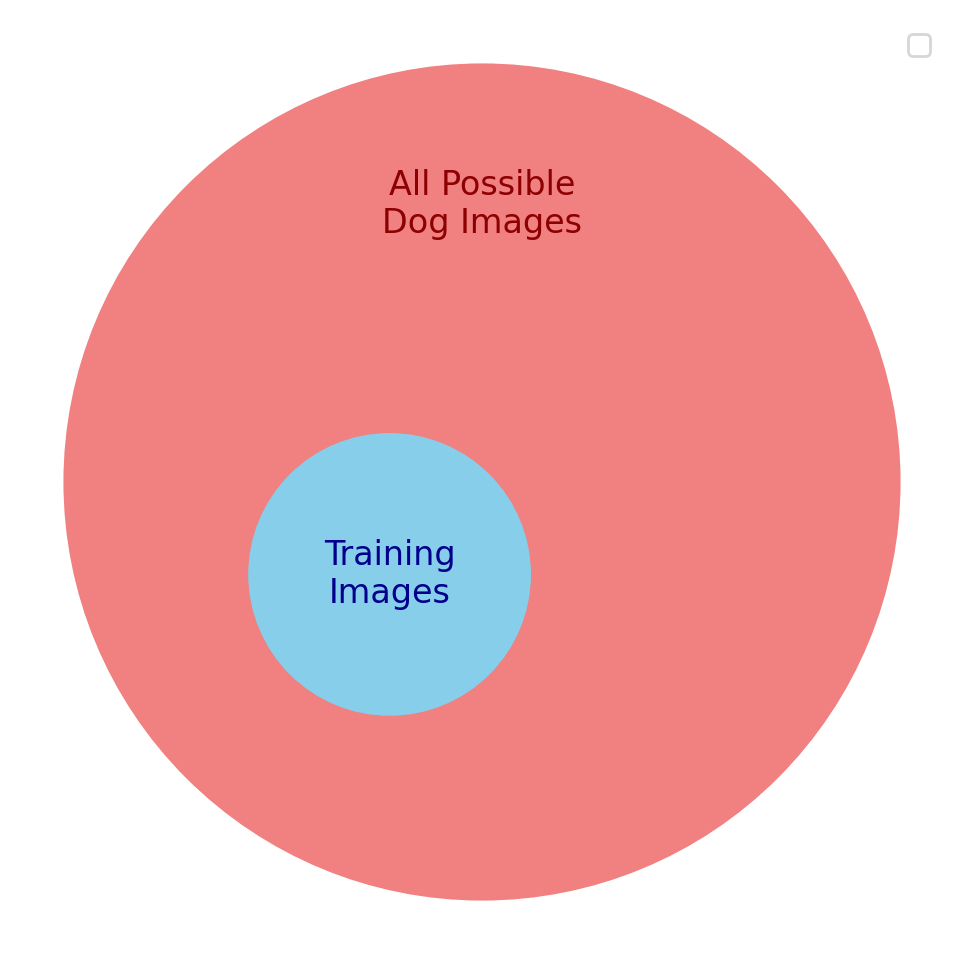

We want the model to be good at labeling pictures of any dog—this is our true objective. But we can’t optimize it for that directly, because we can’t possibly get the set of all possible dog pictures. Instead, we optimize it for a proxy objective: a smaller subset of dog pictures that we hope are representative of the true objective.

There’s a lot of similarity between the proxy objective and the true objective, so at the start, the model gets better at both objectives. But as the model gets more trained, the usable similarities between the two objectives diminish. Pretty soon, the model is only getting good at recognizing what’s in the training set, and bad at anything else.

The more the model is trained, the more it starts to get too attuned to the details of the dataset you trained it on. For example, maybe the training dataset has too many pictures of yellow labradoodles. When it’s overtrained, the model might accidentally learn that all yellow dogs are labradoodles.

When presented with new images that don't share the same peculiarities as the training dataset, the overfitted model will struggle.

Overfitting illustrates an important point in our exploration of goal optimization.

First, when you’re trying to optimize anything, you’re rarely optimizing the thing itself—you’re optimizing a proxy measure. In the dog classification problem, we can’t train the model against the set of all possible dog images. Instead, we try to optimize for a subset of dog pictures and hope that works well enough to generalize. And it does—until we take it too far.

Which is the second point: when you over-optimize a proxy function, you actually get quite far away from the original goal you had in mind.

Once you understand how this works in machine learning, you’ll start to see it everywhere.

How overfitting applies to the real world

Here’s an easy example:

In school, we want to optimize learning the subject matter of the classes we take. But it’s hard to measure how well you know something, so we give out standardized tests. Standardized tests are a good proxy for whether you know a subject—to some degree.

But when students and schools put too much pressure on standardized test scores, the pressure to optimize for them starts to come at the cost of true learning. Students become overfitted to the process of increasing their test scores. They learn to take the test (or cheat) in order to optimize their score, rather than actually learning the subject matter.

Overfitting occurs in the world of business, too. In the book Fooled by Randomness, Nassim Taleb writes about a banker named Carlos, an impeccably dressed trader of emerging-market bonds. His trading style was to buy dips: when Mexico devalued its currency in 1995, Carlos bought the dip, and profited when bond prices rallied upward after the crisis was resolved.

This dip-buying strategy netted $80 million in returns to his firm over the years he ran it. But Carlos became “overfitted” to the market he’d been exposed to, and his drive to optimize his returns did him in.

In the summer of 1998, he bought a dip in Russian bonds. As the summer progressed, the dip worsened—and Carlos continued to buy more. Carlos kept doubling down until bond prices were so low that he eventually lost $300 million—three times more than he’d made in his entire career to that point.

As Taleb points out in his book, “At a given time in the market, the most successful traders are likely to be those that are best fit to the latest cycle.”

In other words, over-optimizing returns likely means overfitting to the current market cycle. Your performance will dramatically increase your performance over the short run. But the current market cycle is just a proxy for the market’s behavior as a whole—and when the cycle changes, your previously successful strategy can suddenly leave you bankrupt.

The same heuristic applies in my business. Every is a subscription media business, for which I want to increase MRR (monthly recurring revenue.) To optimize for that goal, one thing I can do is to increase the traffic to our articles by rewarding writers for getting more pageviews.

And it will likely work! Increased traffic does increase our paid subscribers—to a point. Past that point, though, and I bet writers would start driving pageviews from clickbait-y or salacious articles that wouldn’t draw in engaged readers who want to pay. Ultimately, if I turned Every into a clickbait factory, it would probably cause our paid subscribers to shrink instead of grow.

If you keep looking at places in your life or your business, you’re bound to find the same pattern. The question is: what do we do about this?

So what do we do about it?

Machine learning researchers use many techniques to try to prevent overfitting. Jascha’s article tells us about three major things you can do: early stopping, introducing random noise into the system, and regularization.

Early stopping

This means consistently checking the model’s performance on its true objective and pausing training when performance starts to go down.

In the case of Carlos, the trader who lost all of his money buying bond dips, this might mean a strict loss control mechanism that forces him to unwind his trades after a certain amount of accumulated loss.

Introducing random noise

If you add noise to the inputs or the parameters of a machine-learning model, it will be harder for it to overfit. The same thing is true in other systems.

In the case of students and schools, this might mean giving standardized tests at random times to make it harder to cram.

Regularization

Regularization is used in machine learning to penalize models so that they don’t become too complex. The more complex they are, the more likely they are to be overfitted to the data. The technical details of this aren’t too important, but you can apply the same concept outside of machine learning by adding friction to the system.

If I wanted to incentivize all of our writers at Every to increase our MRR by increasing our pageviews, I could modify the way pageviews are rewarded such that any pageviews above a certain threshold count for progressively less.

Those are the potential solutions to the problem of overfitting, which brings us back to our original question: what is the optimal level of optimization?

The optimal level of optimization

The main lesson we’ve learned is that you can almost never optimize directly for a goal—instead, you’re usually optimizing for something that looks like your goal but is slightly different. It’s a proxy.

Because you have to optimize for a proxy, when you optimize too much, you get too good at maximizing your proxy objective—which often takes you far away from your real goal.

So the point to keep in mind is: know what you’re optimizing for. Know that the proxy for the goal is not the goal itself. Hew loosely to your optimization process, and be ready to stop it or switch strategies when it seems like you’ve run out of useful similarity between your proxy objective and your actual goal.

As far as John Mayer, Dolly Parton, and Aristotle go on the wisdom of optimization, I think we have to hand the award to Aristotle and his golden mean.

When you’re optimizing for a goal, the optimal level of optimization is somewhere between too much and too little. It’s just right.

If you're still curious about this topic I highly recommend reading Too much efficiency makes everything worse for a more in-depth explanation with great practical examples.

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!