When I was 23, I got fired from the only real job I’ve had.

Normally when you’re fired, you start looking for something else. I didn’t. I spent the next year traveling, writing, and seeing what life would be like as a digital nomad.

I was only making a couple grand a month, but I didn’t need to make much. During my job and previous projects I’d hoarded a large amount of cash which gave me the freedom to take some time to figure out what to do next. I burned through most of my savings that year, which might seem irresponsible, but was one of the smartest financial decisions I’ve made.

I hadn't followed the normal financial advice. I maxed out my IRA every year, but that was it. My job didn't have a 401k, and I didn't contribute to my SEP IRA with my side income.

I just kept it all in cash. And it turned into enough cash to spend a year learning, exploring, and figuring out what to focus on.

If I had followed the standard financial advice, most of that cash would have been locked up in retirement funds, and I would have felt much more pressure to find a new job. If I’d jumped into another job, my site wouldn’t be what it is today, and I never would have started Growth Machine.

I think I had ~$30,000 in cash. If I had put that into a retirement fund 100% in the S&P 500, it'd be worth $54,300 today 4 years later. Not bad!

But by not following that advice, that $30k turned into more than 10x that amount. Not to mention all the psychological and emotional benefits that came with it.

Retirement funds are a phenomenal tool if you have no other options available to you. But for anyone remotely entrepreneurial, or unsure about their current career, they might do more harm than good.

In this post I’m going to explore:

- The questionable ROI benefit of tax-advantaged retirement funds

- The good and bad of focusing on compound interest

- Lump wealth

- Hidden, unmeasurable ROIs

- The best investment we can make

The Questionable ROI of Tax-Advantaged Retirement Funds

I take no credit for this section. It is inspired by Nick Maggiulli’s excellent post “why you shouldn’t max out your 401k.”

In the post, Nick does a comparison between your lifetime returns from investing in a Roth 401k account vs. investing the same amount into a normal taxable brokerage account.

When he ran the math, in an ideal situation the tax-advantaged account only gets you an extra 0.34% return each year:

“... the Roth 401(k) ends up with 14.5% more than the taxable account after 40 years. However, on an annualized basis that 14.5% is only an extra 0.34% (34 basis points) per year. That’s it. You get 34 basis points a year to lock up your capital until you are 59 and 1/2.”

That math gets even worse when we factor in the more expensive funds that often make up 401k plans:

“Coincidentally, the average American typically pays about 0.45% in 401(k) fees each year. This means that the typical American’s 401(k) plan provides no long-term benefit (beyond the employer match) relative to a well-managed taxable account.”

When we compare using a normal brokerage account with a traditional 401k, the results aren’t much better. As Nick points out, the main factor is going to be your tax rate in retirement. If it’s higher than your rate now, you’re actually making a bad bet by investing in your 401k. Meanwhile the absolute best case scenario is you make an extra 1% per year, but only if your tax rate is 0% in retirement.

This also assumes taxes aren’t going to go up in the future, but Nick argues (and I agree) that they probably will. So there’s an even greater chance that you might end up paying more in taxes in the future, wiping out any benefit to the traditional 401k.

Now one caveat: if your employer offers any kind of matching, then you should absolutely contribute that amount to your 401k. It’s an immediate 100% return on your investment, you’re not going to find a better deal than that.

But should you invest beyond that amount? Purely from a numbers standpoint, it doesn’t look like there’s much of an argument to do it. But there are other reasons that might be compelling beyond just the ROI.

For example, it’s a way to force yourself to save and prevent yourself from doing something stupid with the money. I find this pretty compelling: we all have much less willpower than we think we do, so hiding money from ourselves is often a good strategy.

But is that a good enough reason?

The Good and Bad of Compound Interest

We know the great part about compound interest: as an account grows and compounds upon itself, the amount it grows by also increases, which is why $10,000 compounded at 7% will only reach $20,000 in 10 years, but then reach $40,000 in 20.

The bad part about compound interest is that unless you have a large sum to get started, the growth is pretty slow in the beginning. The whole point of having a large investment account is to someday have the option to live off of it, but if you only have $40,000 saved you’re not going to be able to support yourself for very long.

There are certainly a few brave Mr. Money Mustache type people out there who can dramatically reduce their consumption, save aggressively, and retire unusually early, but they’re the exception to the rule. And even in Mr. Mustache’s case, most of his money now apparently comes from his site, not from all the saving and investing he did.

The problem with compound interest is that it’s so damn slow in the beginning. You need a big amount for those 7% returns to get interesting. In percentage of growth terms, the 7% stays the same and seems great, but when we consider the real amounts, it’s not so impressive.

Put another way, do you think that, over the course of a year, you could find a way to turn $10,000 into $10,700? If the answer is yes, then you shouldn’t necessarily put that amount into a retirement account. As long as you’re dealing with small amounts, normal market returns are probably going to be much slower than what you could reasonably accomplish by investing that money in yourself.

The other problem with compound interest is that it creates this idea of slow & steady growth as the goal. When in reality, a lot of wealth gets built suddenly and quickly.

Sudden Wealth vs. Slow Wealth

The slow compounding retirement account is a fine model to follow if you want to work a normal 9 to 5, rise through the ranks, and comfortably retire someday. But if you want to FatFIRE, get Fuck-You Money, or however you wanna frame it, slow and steady is probably not how it’s going to happen. A lot of massive wealth is generated very slowly, then very quickly.

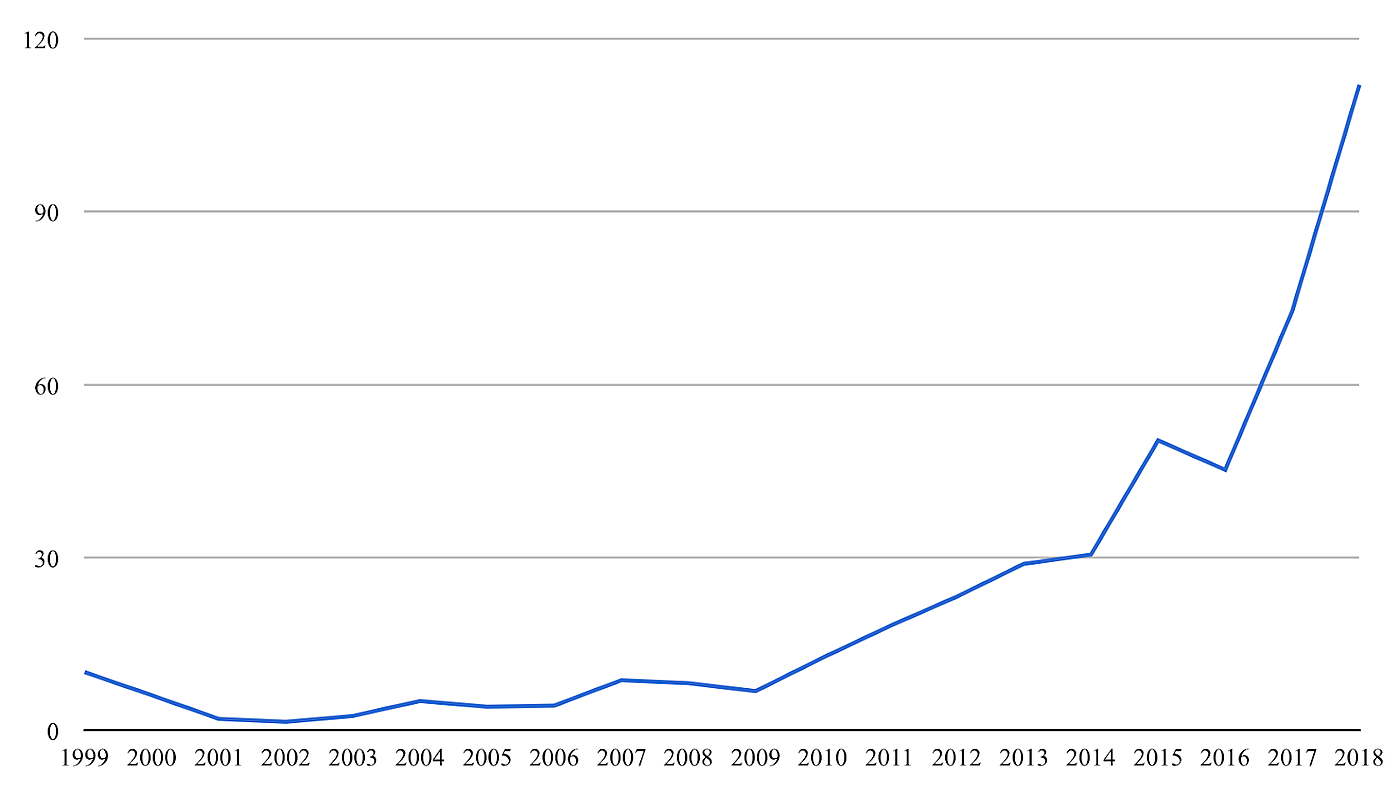

Here’s a chart of Jeff Bezos’s net worth since 1999 (source: Wikipedia):

I know it’s in billions, bear with me. It was flat for 10 years before really starting to increase in 2010, and the rate of change in 2016-2020 is the craziest. And what’s not included is the first 35 years of his life where his net worth would not have even registered on the chart.

No growth for a long time, a huge surge when Amazon IPOd, no growth for a while, then another huge surge over the last 10 years. It’s not slow and steady, it’s choppy and dramatic.

Anyone who sells their company is going to have a similar story. Many years of little increase in their wealth and lifestyle, followed by a dramatic surge, then hopefully slow and steady growth on that new sum assuming they don’t roll it all into something that fails.

The big downside of taking a salary and investing it into index funds is that you have a 0% chance of sudden wealth. Your odds of sudden wealth when investing in yourself isn’t 100%, but it’s not 0% either.

Not everyone wants to be an entrepreneur though, nor should they be. But even without considering sudden wealth and the massive ROI you can get from self-investment, there are a lot of other benefits of freeing up cash that are harder to quantify.

The Unmeasurable ROIs

People with an entrepreneurial bent seem to understand the “systems mindset” much better than their non-entrepreneurial peers. Part of it comes from realizing that you can use your time to create wealth. As soon as you learn that, you become better at spending money to either increase your wealth or provide you joy.

If you lock all of your money into retirement accounts, you might maximize your financial ROI on your money, but not your emotional ROI.

How much extra retirement cash is worth giving up time on the weekends with your kids, because you don’t want to pay someone to do your laundry and manage your yard?

What’s the annual return on having a computer and phone fast enough to never delay your work?

What’s the 30 year compound return on sleeping the best you possibly can?

There are so many areas where we can spend money to dramatically improve our life that we might not have the budget for if we lock all of our extra cash up in retirement funds. What’s the point of a comfier retirement if you lose one day per week with your kids? Or if you ate low-quality food to save money, and cut years of health off that retirement life you were saving for? Obviously the feasibility of that decision making is going to depend on your level of income, but if you have the option to ask those questions, they’re worth asking.

And then we get to the greatest ROI investment we have: investing in ourselves.

Investing in Ourselves

At smaller net worth levels, it’s hard to argue that we’ll get better returns in the market than we would by investing ourselves and our career capital.

If you have $5,000 and you could invest that in either the stock market, or a premium course like Building a Second Brain, the premium course is probably the better option.

$5,000 compounded at 7% for 10 years is only going to reach about $10,000. But could you create more than $1,000 a year in additional income by investing in learning a system for better capturing and harnessing information? Absolutely.

This is why I lean on the side of investing heavily in ourselves while our net worth is lower, and then slowly increasing how much of our income goes into safer diversified assets as our net worth increases. If you have $20,000 of allocatable savings per year, investing in yourself is probably going to have the highest returns.

But if you have $200,000 to allocate, it gets harder to find high ROI ways to invest in yourself and diversifying into safer assets gets more and more attractive.

Afterword: Walking the Talk

I try not to talk about personal finance without “walking the talk,” so here’s how I’m following the ideas in this article.

I contribute to my 401k enough to get the 6% match from Growth Machine, but I don’t contribute more than that.

Then I max out my backdoor Roth IRA. But I don’t contribute to a SEP IRA or anything else, that’s it. The rest goes primarily into savings, with some percentage going into index funds just to help hide money from myself.

Could I cut the IRA investment as well? Sure, but the $6,000 a year isn’t a huge amount and I figure I may as well do it as a small hedge against my own impulsivity.

But with the bulk of my income going into cash or easily liquidated index funds, I have a lot more freedom to invest in real estate, startups, and whatever else looks interesting.

What did you think of this article?

The Only Subscription

You Need to

Stay at the

Edge of AI

The essential toolkit for those shaping the future

"This might be the best value you

can get from an AI subscription."

- Jay S.

Join 100,000+ leaders, builders, and innovators

Email address

Already have an account? Sign in

What is included in a subscription?

Daily insights from AI pioneers + early access to powerful AI tools

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!