It Is Always Time to Build

Interest rates do not equal innovation rates

There are some dumb ideas online that I am compelled to correct. Like this:

or this:

Or this paragraph from the otherwise excellent Newcomer newsletter: “There’s an argument that the best time to invest in bet-the-farm, wildly optimistic companies are [sic] already in the rearview mirror. When interest rates were essentially at zero—as they were for much of the past decade—that was the time to change the world. Now markets are pressuring companies to show they can turn a profit and deliver cash flow in the near term.”

The sentiment that low interest rates made highly risky companies fundable is one that has come up again and again in my private conversations with venture capitalists. There is this tribal belief that because interest rates are higher, it’s time for “safer” startups to prevail.

They are wrong.

While there is some merit to the idea that when interest rates are lower, risky ideas are funded because returns are more challenging to find, it misses how great companies begin. If you’ve read the histories of Gates, Jobs, Ford, or Edison, they didn’t worry about federal interest rates when they started their companies. Technology companies came to be because scientific advancement met charismatic founders and risky happy financiers.

Increased interest rates have a dampening effect on investment decisions but do not dampen innovation decisions.

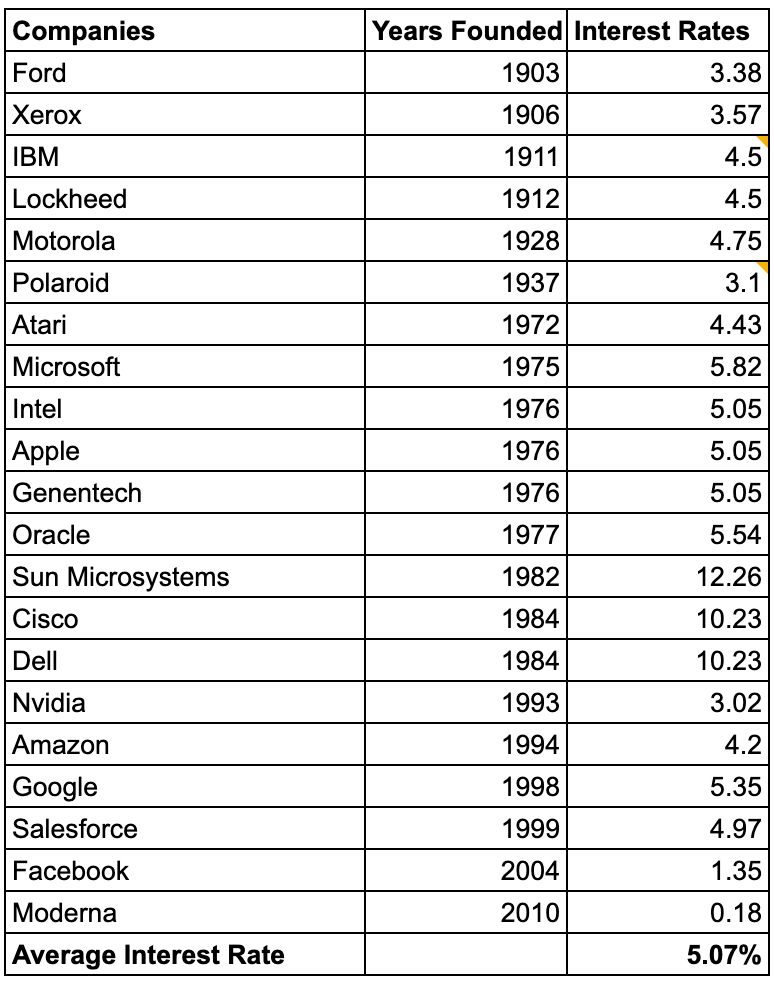

To move beyond hyperbole, I pulled the interest rates for when 21 of the greatest technology companies of the last 100 years were founded.

The average? 5.07%.

Only about 5% higher than what has happened over the last ten years.

Note: Federal interest rates are available after 1950, but to look earlier I had to substitute municipal bond rates and high-quality corporate bond rates.

If interest rates were the primary driver of “world-changing” companies, I would expect to see greater clumps of tech companies being founded when rates were lower. Instead, my handy correlation function on Google Sheets tells me that there is a .105 correlation—which means there’s very little relationship between the two. For context, a 1 would be a perfectly positive correlation.

This error seems to be driven by people forgetting what a technology company is.

What gives birth to technology

The movies portray the invention of new tech as a eureka moment—a point in time when the lightbulb goes off and genius appears unbidden. The actual inventor of the lightbulb would disagree.

Edison insisted that “I never had an idea in my life. My so-called inventions already existed in the environment—I took them out. I’ve created nothing. Nobody does. There’s no such thing as an idea being brain-born; everything comes from the outside.” Edison’s lightbulb had already been invented in 1840. It wasn’t until 1879 that Edison discovered the incremental innovation of passing electricity through a carbonized cotton filament to produce consistent light for 40-plus hours. But still, that wasn’t enough—the lightbulbs needed power, so in 1880 he incorporated Edison Machine Works to manufacture generators. Edison’s consistent innovation was driven by tinkering, by genius, by scientific advancement. Edison himself would argue that he took advantage of pre-existing scientific techniques in new commercial applications.

It’s also important to note that Edison lost the electricity race! We always gloss over that part of technology history. Despite the benefit of his genius, Edison had to sell to his competitor in 1892 to form General Electric. GE would go on to be the most important technology company of the next 50 years, not Edison’s independent company.

Fast-forward 115 years. Once again, a larger-than-life personality was hunting for his next big thing.

For months Steve Jobs had been relentlessly pushing his engineers to make a multi-touch display on their secretive iPhone project. The tech was new, but they figured it could work. To make the product really shine, Jobs desperately wanted a glass display. He sat down with Kentucky-based Corning CEO Wendall Weeks to describe what he wanted, as Walter Isaacson described in his biography of Jobs.

“Jobs described the type of glass Apple wanted for the iPhone, and Weeks told him that Corning had developed a chemical exchange process in the 1960s that led to what they dubbed ‘gorilla glass.’ It was incredibly strong, but it had never found a market, so Corning quit making it. Jobs said he doubted it was good enough, and he started explaining to Weeks how glass was made. This amused Weeks, who, of course, knew more than Jobs about that topic.

‘Can you shut up,’ Weeks interjected, ‘and let me teach you some science?’

Jobs was taken aback and fell silent. Weeks went to the whiteboard and gave a tutorial on the chemistry, which involved an ion-exchange process that produced a compression layer on the surface of the glass. This turned Jobs around, and he said he wanted as much gorilla glass as Corning could make within six months.

‘We don’t have the capacity,’ Weeks replied. 'None of our plants make the glass now.’

‘Don’t be afraid,’ Jobs replied.”

Once again, an iconic company and product were built with science repurposed to a particular market opportunity.

Oh—and the interest rate during the invention of the iPhone? 5.24%.

The ignorance arbitrage

A technology company is exactly as its moniker describes:

- Technology: utilizes a new commercial application of science

- Company: addresses a market opportunity previously untouched by said technology to reduce costs or improve customer utility

The last decade of fiscal excess has perhaps shown the opposite of the conventional wisdom about interest rates. Higher interest rates increase the formation rate of companies, not technologies. Truly ambitious projects that use new science to address a market opportunity are still going to be funded. What won’t get funded is your stupid niche Bernadoodle NFT app (RIP). I expect we’ll still see space, AI, climate change, and biotechnology startups receive funding because that is where science is progressing the fastest.

It might look like entrepreneurship is suffering, but the only people who are really suffering are grifters. So many of the companies from this last bull cycle weren’t built on remotely new technology but instead mostly applied the same existing technology to ever smaller niches. My personal rule of thumb: if there is a well-defined playbook on how to build your type of company, you aren’t a true tech startup; you’re a regular company performing arbitrage on your competitors’ technological ineptitude. That is totally ok! But it’s very different from the tech startups of yesteryear.

I expect that fewer “startups” will be formed during this period of interest rates. But the limiter is science, not capital. With capital more difficult to acquire, niche, non-differentiated startups—not ones that change the world—will disappear.

Whenever there is a scientific advancement, regardless of interest rates, there will be an explosion of new companies—hence why whenever there is a new unlock in capability, there will be multiple companies all trying a similar approach, with a similar technology stack, with a similar business model, until they consolidate. See how our homegrown GPT-3 word processor spawned more than 492 competitors. AI offered a new science unlock, and the race is on to apply it as a technology company.

Interest rates are important to consider when forming a company, but to categorically state that they are the important driver of technology companies is nonsensical. Technology companies are built with science, ingenuity, and sheer hustle to find and capitalize on a market opportunity. Regardless of the interest rate, it is always time to build.

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!