What do you think?

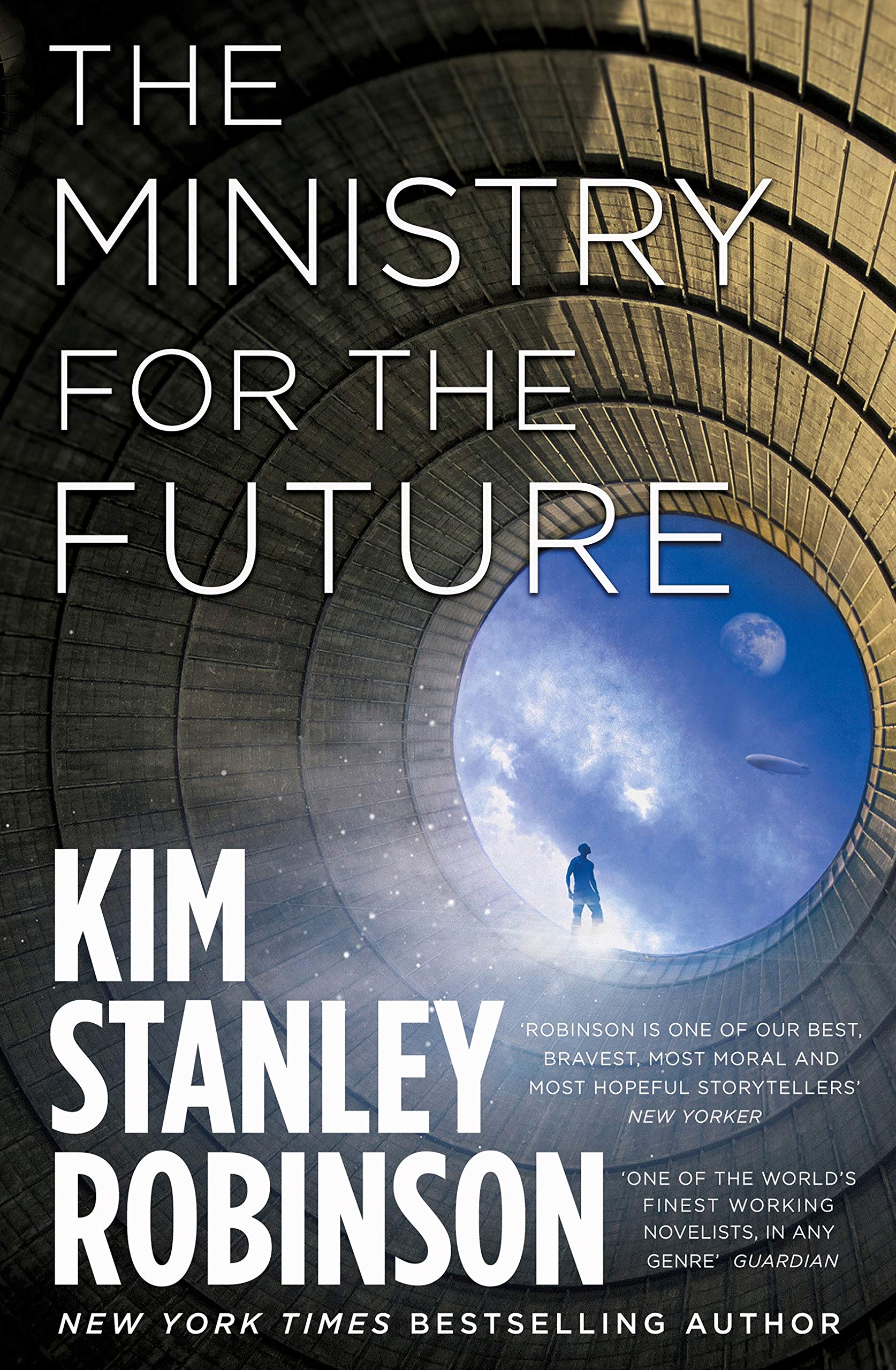

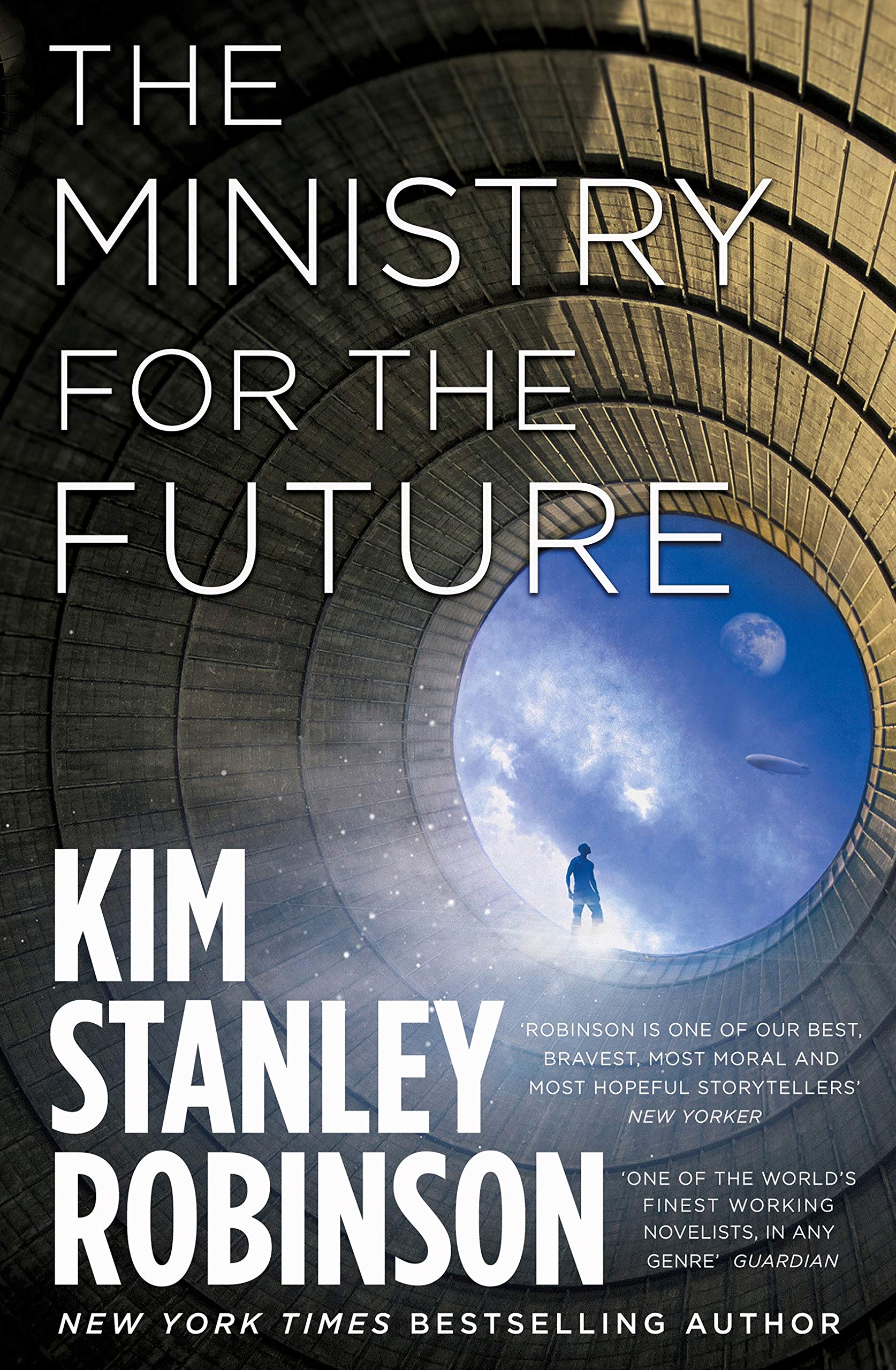

Rate this book

563 pages, Hardcover

First published October 6, 2020

John Maynard Keynes, the chief British negotiator, also suggested at Bretton Woods that they found an International Clearing Union, which would make use of a new unit of currency to be called a bancor. The purpose of the bancor would be to allow nations with trade deficits to be able to climb out of their debts by calling on an overdraft account with the ICU that would allow them to spend money to employ more citizens and thus create more exports. Nations making use of their overdraft would be charged 10 percent interest on these bancor loans, which could not be traded for ordinary currencies, or by individuals. Nations with large trade surpluses would also be charged 10 percent interest on these surpluses, and if their credit exceeded an allowed maximum at the end of the year, the excess would be confiscated by the ICU. Keynes thus hoped to create an international balance of trade credit which would keep countries from becoming either too poor or too wealthy.