Blind Ambition

Big tech’s highest-paid workers get real on an anonymous professional social network

“What the actual fuck? I didn't sign up for this.”

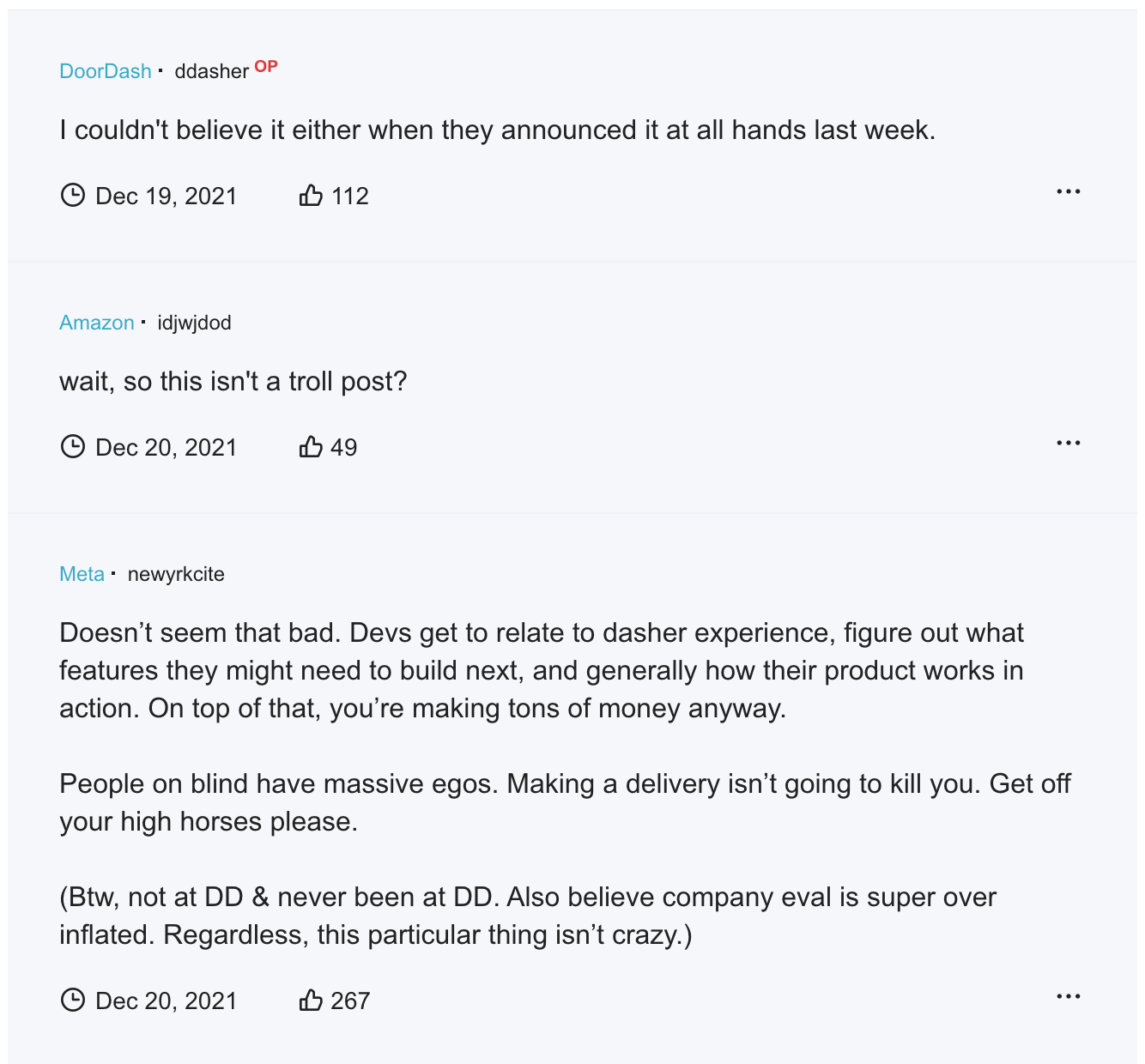

Exasperated by an internal policy at work, a Doordash engineer started a conversation on Blind, the tech industry’s semi-anonymous professional social network. In a thread titled “Doordash making engineers deliver food,” the poster documented their indignation at Doordash’s policy requiring all employees to complete one customer food delivery each month. “...[T]here was nothing in the offer letter or job description about this,” they added, alongside their annual total compensation of $400,000.

The December 2021 discussion on Blind garnered over 2,000 comments from fellow tech workers across the industry. Reactions ranged from concerned solidarity (“If that happens, [A]mazon will force all employees to do parcel delivery”), to enthusiastic admiration (“What a fantastic push from leadership to become more customer centric”), to disgusted disbelief (“Wow, what an entitled person you are. You’re making that much money, but cannot deliver food 1/month?”).

The conversation spilled onto Twitter and Reddit, and also received coverage from mainstream media outlets like CNN Business, Business Insider, Forbes, Inc., and SFGate. Doordash made a statement to CNN Business about WeDash, the internal program in question. The discussion is just one instance of how Blind reveals the inner workings of some of the biggest companies in the industry, through candid anonymous posting from the highest-earning tech workers.

The tech industry is marked by optimism—whether it’s the Y Combinator motto of “build something people want” or web3 enthusiasts at the decentralized frontier chanting “WAGMI (we’re all gonna make it).” It’s common for startups to pay homage to early tech pioneers, while simultaneously setting out to build a technological future that eclipses the past and disrupts the present. But techno-optimists will find little discussion in this tradition on Blind.

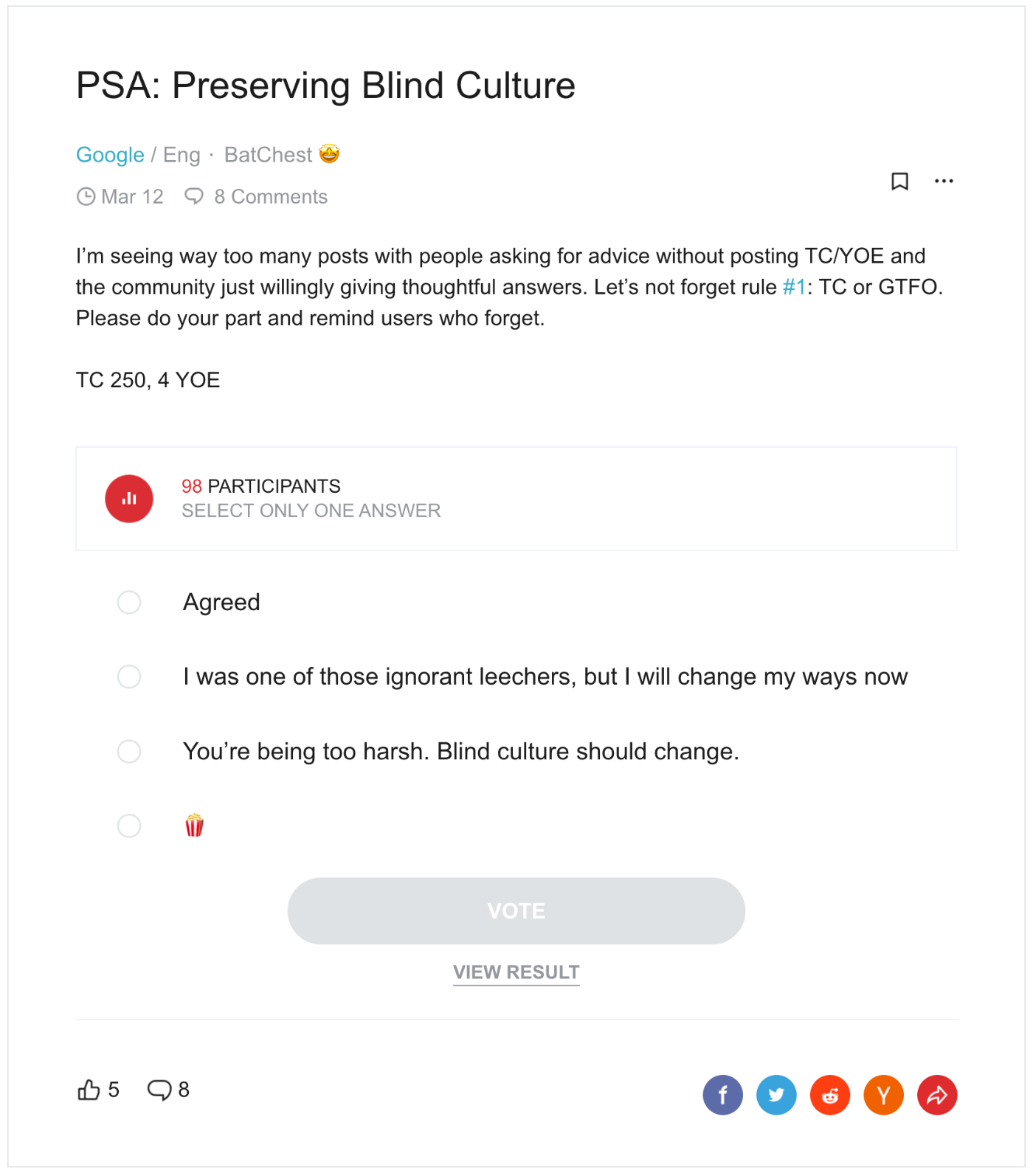

The specific corner of the tech industry active on Blind is flush with money and people trying to optimize for more—whether it’s collecting information to negotiate the best offer or job-hopping their way to higher total compensation (TC). The refrain “TC or GTFO” is persistent on Blind. It signifies that career conversations should center around weighing six-figure salaries, and that discussions about work without mention of money aren’t worth having.

Blind isn’t representative of the entire technology industry—big tech or otherwise. But for many on the app, big tech is a game and big money is the score. The idea that the best is elsewhere is intrinsic to the community, with tech workers bouncing from Meta to Microsoft or vice versa, to maximize their earnings in a compensation climate that often rewards leaving instead of staying. The app captures a culture obsessed with optionality.

And yet, despite the sky-high salaries, lucrative stock options, and generous perks that are a feature of big tech, negativity towards work is pervasive across the app. Much of the conversation is similar in spirit to what you might find on r/antiwork on Reddit or any other space where one speaks candidly about work. People are burnt out, facing a crisis of meaning, and hoping to find salvation up the ladder at a higher salary band or at a shinier brand.

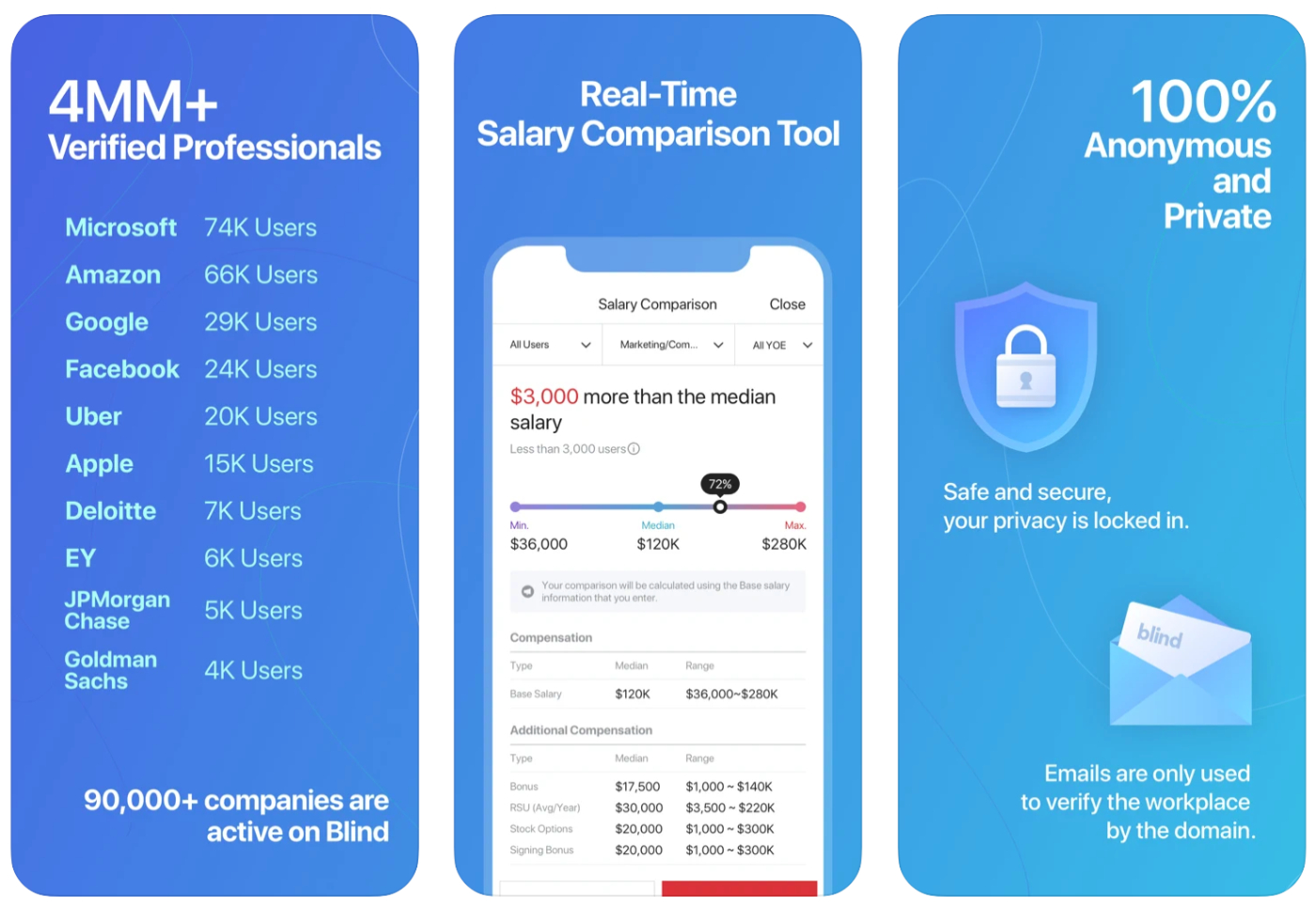

Founded in 2013 in South Korea and available in the U.S. two years later, Blind describes itself as “a trusted community where more than 5M+ verified professionals communicate anonymously.” The platform is accessible through their mobile apps and website. You’ll need a verified corporate email address to participate (a personal email address will get you view-only access to limited content)—the company’s App Store listing claims “87,000+ companies are already on Blind.”

Users commonly come from tech and, to a lesser degree, finance. And despite the range of startups and scale-ups that make up most of the tech ecosystem, conversations on Blind revolve around a handful of big companies. Discussions are generated by a small but specific faction of employees—mostly software engineers that presumably, similarly to the demographics in tech, skew male—working at FAANG companies. Blind boasts 74,000 users from Microsoft, 66,000 from Amazon, 24,000 from Facebook, 20,000 from Uber, and 15,000 from Apple.

Text-based with an understated design, the app feels like a blend of Glassdoor and Reddit. Users transparently share their salaries, seek out referrals while on the job hunt, or review and rate the companies they work for. They also gossip about internal happenings at their companies, discuss broader themes in the technology industry, and swap stories about the cultural elements of tech hubs like the San Francisco Bay Area and Seattle—like dating difficulties or an increasingly impenetrable housing market. While the app has been described as pseudonymous, users can change their username once a day, removing the single identity feature that’s common for pseudonymity. Members can start threads and chime in on discussions anonymously, with only their company affiliation appearing next to their post. The app promises a veil of privacy and the assurance that your anonymity is protected.

In May 2021, Blind raised $37 million in funding, and the company plans to generate revenue by providing anonymized aggregated reporting on company sentiment to employers. Blind is also building tooling to sell to recruiters—”Talent by Blind” is already in beta. The company’s recent funding round lines up with a surge of activity on the app during a tumultuous time for the state of work. The Great Resignation, ignited by the pandemic, has led to changes across the tech industry—and workers have flocked to Blind to talk about it.

The app has categories of conversations including “Return to Office,” “Work From Home,” “COVID-19,” “Layoffs,” and “Job Openings.” A March 2020 post at the start of the pandemic titled “Companies NOT doing WFH” asks users to “name and shame” companies without a work from home policy, garnering 58,400 views and 1,449 comments. Two years later, coinciding with returns to the office, a March 2022 thread from a Meta employee discusses “Meta cutting benefits ruthlessly,” including perks like laundry and to-go boxes for taking home free food. That employee’s “TC” is $850,000

The technology industry is a vehicle for individual wealth generation like few other industries are, with possibilities including an acquisition exit, an IPO, or RSUs. A large contingent of users on Blind view tech as a game to be won: witness a discussion on how to get to $1 million in total compensation or a polls on the highest-paying FAANGs. Through the stream of conversations happening on the app, you can watch as people get into the game, playing to win—but often becoming disenchanted, failing or burning out, or opting out entirely, taking their pieces off the board.

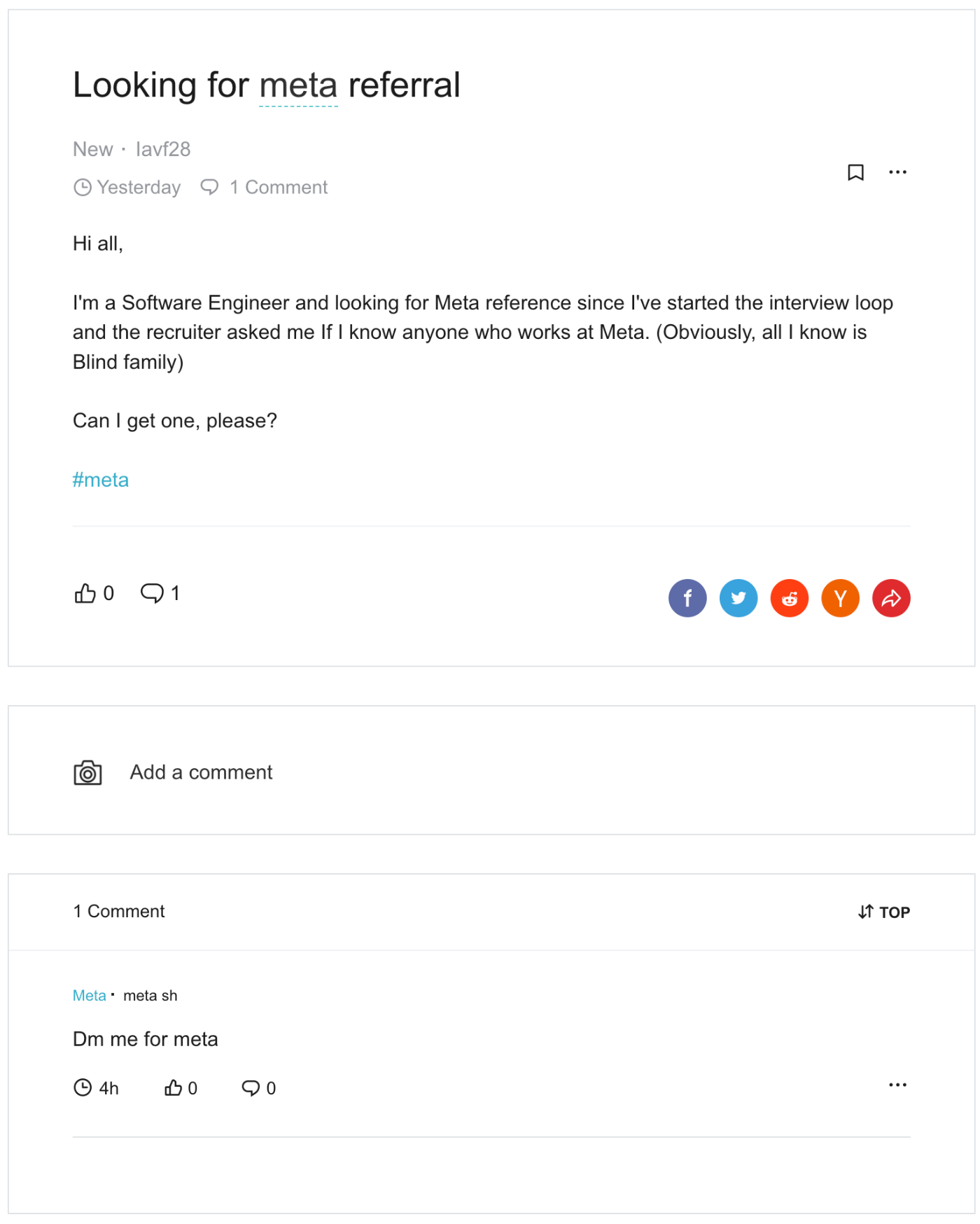

Playing the game starts with getting in the room where it’s happening. Working in the technology industry has been glamorized to the point of becoming a robust content category across social media platforms—on TikTok, #breakintotech has over 40 million views across video on how to get a tech job with high pay, low credentialism, and a level of work-life balance uncommon in fields like consulting or finance. On Blind, those seeking new opportunities at tech companies start threads requesting referrals. Companies hiring through referrals from current employees is an open secret in the tech industry, though less known outside it. Referrals are generally meant to serve as recommendations for people you can vouch for, like former colleagues, friends, and mentees. But because employees are often incentivized through referral bonuses that range from thousands to tens of thousands of dollars, especially for technical roles, requests for blind referrals on the app are both common and unsurprising: “Senior backend engineer looking for referrals”; “anyone working in Airbnb, looking for a referral.” Strangers solicit referrals from strangers, who, with referral bonus checks in mind, gladly oblige.

In a thread where users discuss the diminishing value of referrals when people simply refer strangers, one user rebuffs: “Referrals are the best thing on [B]lind. They give a shot for anyone to interview anywhere.” Applying for a role at a big tech company is generally competitive. In 2019, Google received 3.3 million applications with a hiring rate of only 0.2%. More likely than not, a cold application to one of these companies means having your resume enter a digital void and never hearing back. If you have a connection to a current employee, a referral can help your chances.

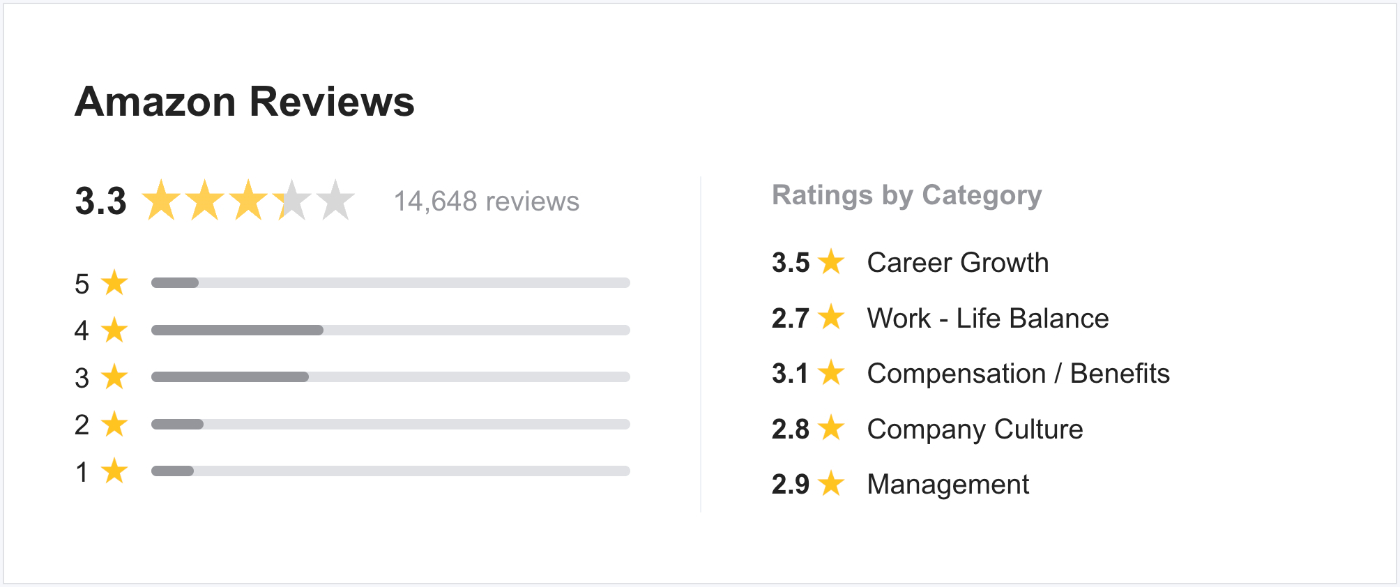

Blind touts this kind of opportunity for job seekers in its mission: “Blind is a platform for change. Our mission towards transparency breaks down professional barriers—empowering informed decisions and inspiring productive change in the workplace.” Job seekers brush up against information asymmetry—an applicant often knows very little while companies that are hiring know everything. On Blind, similarly to Glassdoor, users can rate the companies they work for, increasing the amount of available information about the internal sentiment. Google, one of the highest-rated companies on Blind, has 4.3 stars from over 5,000 reviews—a current software engineer notes, “[O]ther than the entitlement, it’s great.” Amazon has 3.3 stars from over 14,000 ratings—a current Data Scientist II describes being a “cog in a machine.” The company pages on Blind provide insight for prospective employees that can help inform their career decisions.

After a series of interviews, assessments, and take-home assignments—about all of which people can seek advice on Blind—successful applicants receive an offer letter. This is where Blind really shows its function: anonymity allows users to share transparent information around pay, benefits, and offers. Software engineers are generally the most highly compensated employees in tech, other than senior executives. While tech salaries are generally higher across the board compared to other industries, product managers, product designers, sales associates, business development managers, and marketers make comparatively less than their coding colleagues. A disproportionate number of posts on Blind are from software engineers weighing offers that people outside tech might consider fictitious.

One engineer making $320,000 asks for advice on two offers—$347,000 in total compensation at Google or 240,000 at Apple. “Is it possible for Apple to match the number?,” they ask. “What should I expect?” A Senior Product Manager Technical at Amazon making $350,000 asks users to weigh in on their $400,000 offer from Meta. People provide advice on multiple axes, like work-life balance, culture, and “alpha”—information or circumstances that might create upside. Amazon often gets dinged on work-life balance and a culture that’s heavy on performance improvement plans (PIPs) that push low-performing employees—perceived or actual—out the door. Discussions about “alpha” are usually reserved for non-public scale-up companies, like Figma or Notion. Users often recommend side-stepping companies that are too close to IPO, which would disqualify individuals from benefiting from a windfall before vesting, or too far from an IPO, keeping equity granted as a hypothetical until an exit.

But the most important factor that seems to capture the attention of users on Blind is total compensation. “TC or GTFO” is a frequent retort on the app and appears to be both the first consideration and the deal-breaker when it comes down to making a decision between companies. In big tech, it’s common to receive a base salary (e.g., $200,000), as well as a bonus (e.g., $25,000) and RSUs that vest over 3-4 years ($200,000 over four years). In this situation, total compensation (TC) is $275,000 per year, not counting top-tier health care benefits and a bevy of perks. People are often juggling offers from companies that are quite different—Netflix is a streaming service and Microsoft… isn’t. But for all intents and purposes, to members on Blind, most big tech companies are entirely interchangeable and totally fungible. Company culture is irrelevant, and so is what you’ll be working on. Google or Meta? Salesforce or PayPal? Who cares? Your 9-5 belongs to the company with the highest offer. TC or GTFO.

On other corners of Blind, discussions revolve around what working for these big tech companies is actually like. After joining a company, or having been there a few months or years, battling a sense of disillusionment seems to halt any enjoyment that comes with playing the game and taking home the pay. Look up any big tech company on Blind and you’ll find ongoing conversations about a backlash around the return to the office or the level of “personal sacrifice” required to succeed. Most Blind users work for massive companies, and an individual’s experience is largely dependent on the team they land on and their manager—two people across the company might have wildly different experiences. For some, the promise of an incredible culture and work-life balance is a mirage.

Some users claim that their internal messaging at work is censored, and Blind also provides a place where discussions don’t disappear. Aside from public posts, users gain access to an employee-only space that populates after at least 30 employees sign up for the app with a verified company email address. In these single-company-employees-only channels, members discuss the mundane—cringey social media posts from company leaders—and the material—falling stock prices that have impacted total compensation. Communication at tech companies of any size is often monitored, and for those uncomfortable airing their thoughts on internal messaging, Microsoft Teams, or Slack, Blind’s private channels provide the anonymity to speak freely.

Anonymity to share opinions unencumbered comes with the usual benefits and drawbacks. “Any app that centers around anonymous posting is naturally going to feature a lot of content that people feel unable to express publicly—compensation, complaints, gossip, and rants,” says a product manager at Meta with whom I spoke who occasionally uses the app. They suggest that Meta remains a “transparent and open place,” with groups to discuss almost any topic, including compensation. “As long as you’re respectful you can say almost anything,” they say. “The people who feel that they need to post in an anonymous forum either fear repercussions of public posting, know that what they say goes against respectful communication guidelines, or possibly want to lie or exaggerate without repercussion.”.

Because identity is mostly obscured on the app, with only company affiliation and total compensation serving as a stand-in for reputation, the anonymity can surface the negativity lurking within the tech industry. The compensation pecking order that keeps software engineers at the top can translate to a hierarchy of perceived value and importance based on one’s role. Product managers are frequently described as useless while human resources has a reputation on Blind as incompetent.

For non-technical or less technical employees working in tech, the levels of compensation of their software engineering peers, coupled with a perceived sense of entitlement, can make Blind feel negative. “The bravado behind ‘TC or GTFO’ really puts your brain on a one-track mind about getting higher and higher compensation for your work,” adds the Product Manager from Meta. “I found I wasn’t happy seeing people post about how much money they make. Comparing it to my own still very healthy salary…consuming too much of that just makes you miserable.” Says one user on the app, “Reading the amount of TC being offered and negotiated is literally making me ill. It's so clear to me now that I chose the wrong degree and career path.”

“It is wild to see what SWEs are paid and the simultaneous level of entitlement of those individuals,” says an investor and former operator in the tech industry I spoke to who frequents the app. “Never in my life have I seen such a large, powerful group of entitled children. Coming from a blue collar town, I don't think these people realize the level of bubble they are in,” they add.

But some feel the app is not representative of big tech overall. “It is a loud minority who participates on those platforms. 85% of actual employees don’t care about it, and for the most part love their job for the pay to work-life balance ratio,” says Lenny Bogdonoff, the Founder of Y-Combinator backed Milk Studio and a former UX Engineer at Google. “The people who participate on Blind mostly have too much time on their hands. It's really just a subset of people who would spend time on Reddit,” he adds.

For this subset of people, conversations can certainly veer away from the professional, occasionally landing in a territory that explains why some refer to Blind as the “4chan of tech.” Across the app, disturbing discussions around topics like race and gender are not a mainstay, but do occur—in a March 2022 thread, a Meta employee started a conversation on “Asian women and white fever.”

In a Blind post allegedly deleted by the platform, but captured on Twitter in December 2021, a self-identified Asian man working at a FAANG company claimed that in over the 100+ interviews he had conducted at the company, he was lenient in assessing Asian males, white males, and international students from India and China. However, he reserved “extremely high standards” for anyone he claims was an “obvious diversity hire,” citing HBCU applicants as one such example. “I have never passed such a candidate,” he notes. “They’ve stolen spots from asian/white men in the past and therefore I will try to make it even.”

The anonymous nature of Blind lends itself to off-color confessions. It also lends itself to trolling and rage bait. But even if the original poster was engaging in either, according to the person who captured the conversation on Twitter, around 50% of the responses to the thread on Blind were in agreement with the OP before the post was deleted. Black tech workers across the industry, weighing in on the post on Twitter, felt it resonated with their own experiences and observations in tech, arguing that this form of prejudice contributes to the disproportionately low numbers of Black candidates who enter (and stay) in the industry.

“this is why I find it so delusional when ppl assume any Black techie was given anything bc of diversity quotas,” tweeted Angie Jones, a VP at Block with former stints at Twitter and IBM. “I found the Black engineers I referred were often judged more harshly than other candidates (feedback I provided to those workplaces), which I imagine is exceptionally common,” said Cher Scarlett, a former Apple employee who also blew the whistle on the company for alleged labor violations. Prejudice exists across all industries, but Blind provides a specific window into what form it takes in the tech industry, the biases that women and underrepresented minorities run up against, and how that impacts the culture of these companies overall.

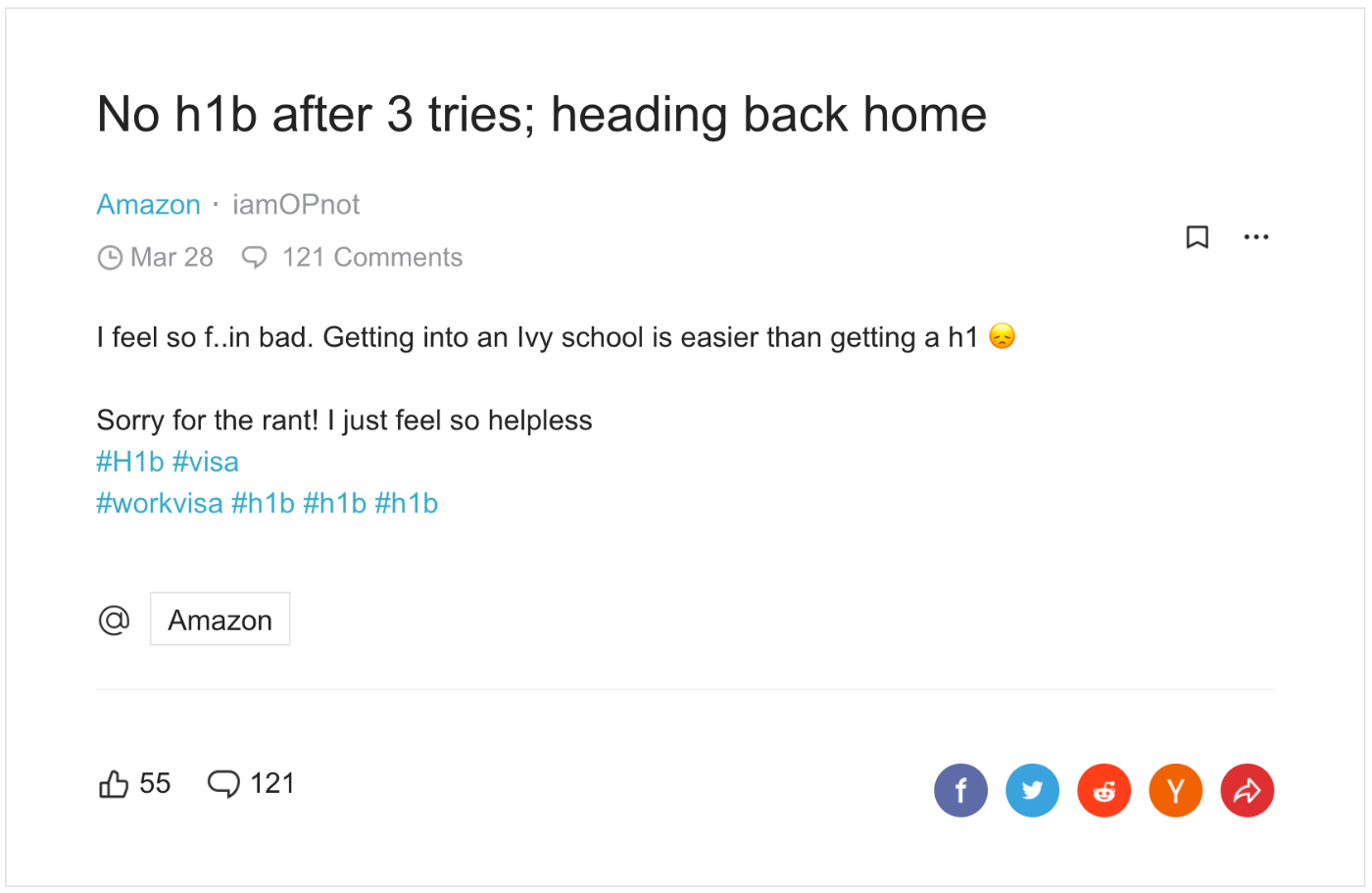

This includes revelations about the tenuous place of foreign workers in the industry. It’s common for companies in tech to hire from countries like India, using the H-1B visa that lets companies temporarily employ foreign workers in specialty occupations—namely, software engineering. Tech workers on this visa are a fixture on the app and further reveal, through their posts, the hierarchy that exists within the industry. Many of their posts are tinged with sadness and desperation—H-1B visa holders are often paid less than their non-foreign peers, are tied to working to one particular company, and face uncertainty about their status in the United States.

But even U.S.-born tech workers, too, seem to be buckling under the stress of working in tech. From toxic culture to burnout culture, you don’t have to do much digging on Blind to continue seeing that “getting into big tech” is not the career panacea that content creators claim.

On much of the app, people are discussing some of the rot of corporate culture from terrible managers to the stress of high-pressure environments to an onslaught of overwork and depression. (For some, this only furthers the difficulty of finding another job—interviewing and prepping is challenging when you’re already burnt out and tired.) Users often make posts about being placed on PIPs, airing their anxieties on the app. PIPs are controversial throughout the tech industry, seen either as draconian schemes to push people out, or as a well-meaning path to improvement that can help employees thrive at the company. But, given the options in tech and the tendency to get a raise when you move companies, particularly for in-demand software engineers, there’s little incentive to stick around and “improve.”

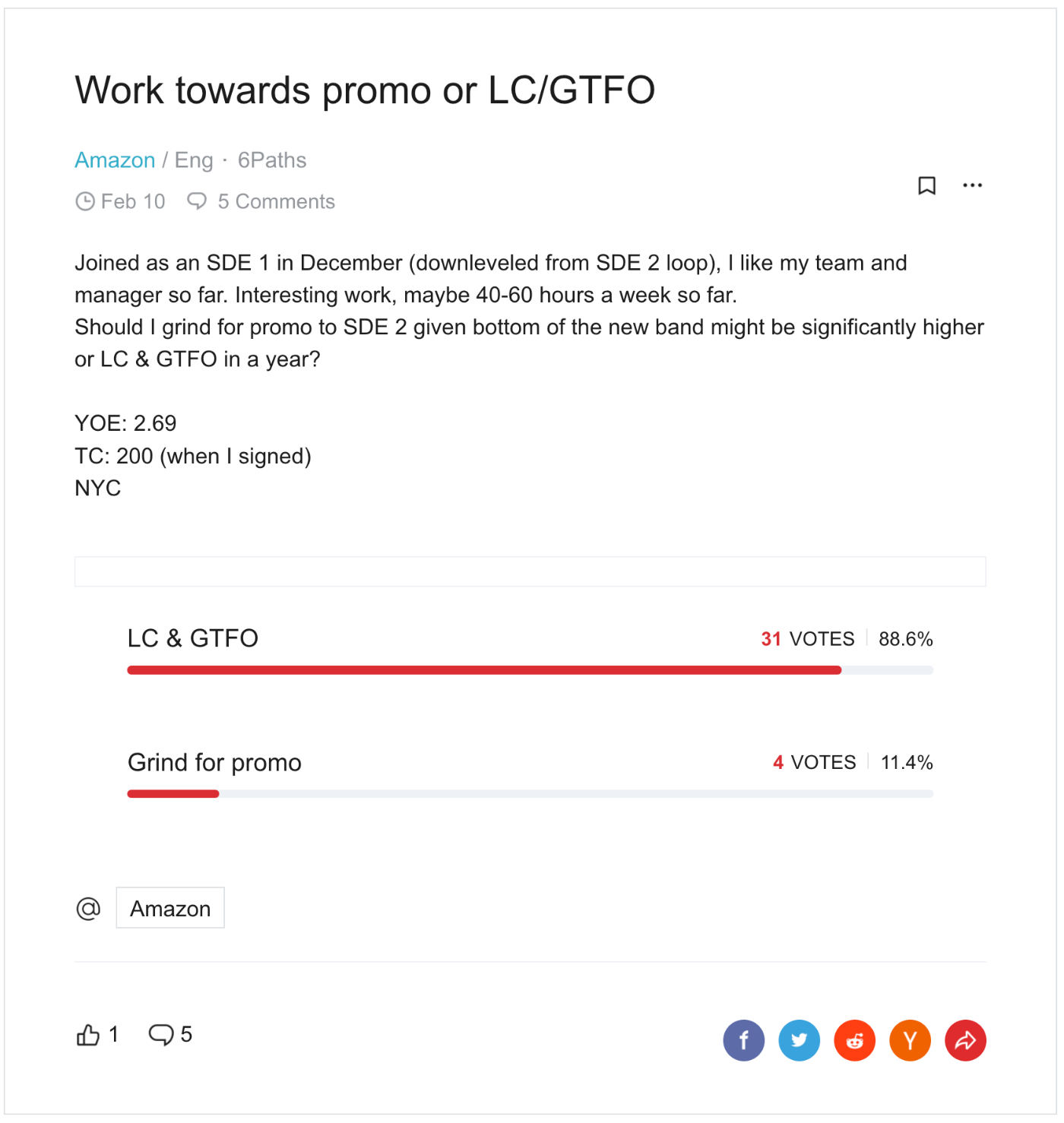

For many users on Blind, when environments become untenable, it’s time to move on. For software engineers, this means spending hours a day preparing for upcoming interviews on Leetcode—a platform to prepare for technical interviews. This culture of optionality means bouncing to the next company as a solution to any problem. When people complain about companies, often the answer is the same: LC and GTFO. A process that starts with referrals also ends with referrals—another chance to play the game and win.

But with the conversations that fly around on Blind, discussing the bad to the terrible within every tech company under the sun, making a switch seems like getting more of the same. When everyone has similar stories, they all seem to collapse into one Big Tech Company. Across companies worth billions, with salaries many multiples of the national average, employees are facing the same isolation, burnout, and professional disenchantment that seems pervasive across the entire economy. One is unequivocally better than the other—but whether you’re making six figures or working paycheck to paycheck, there’s a crisis of meaning at work.

In her book, Work Pray Code: When Work Becomes Religion in Silicon Valley, Carolyn Chen argues that “people are not ‘selling their souls’ at work. Rather, work is where they find their souls.” In the absence of formalized religion, people have replaced work as their object of worship:

“Today, companies are not just economic institutions. They’ve become meaning-making institutions that offer a gospel of fulfillment and divine purpose in a capitalist cosmos. Most Fortune 500 companies have adopted key elements of religious organizations—a mission, values, practices, ethics, and an ‘origin story.’”

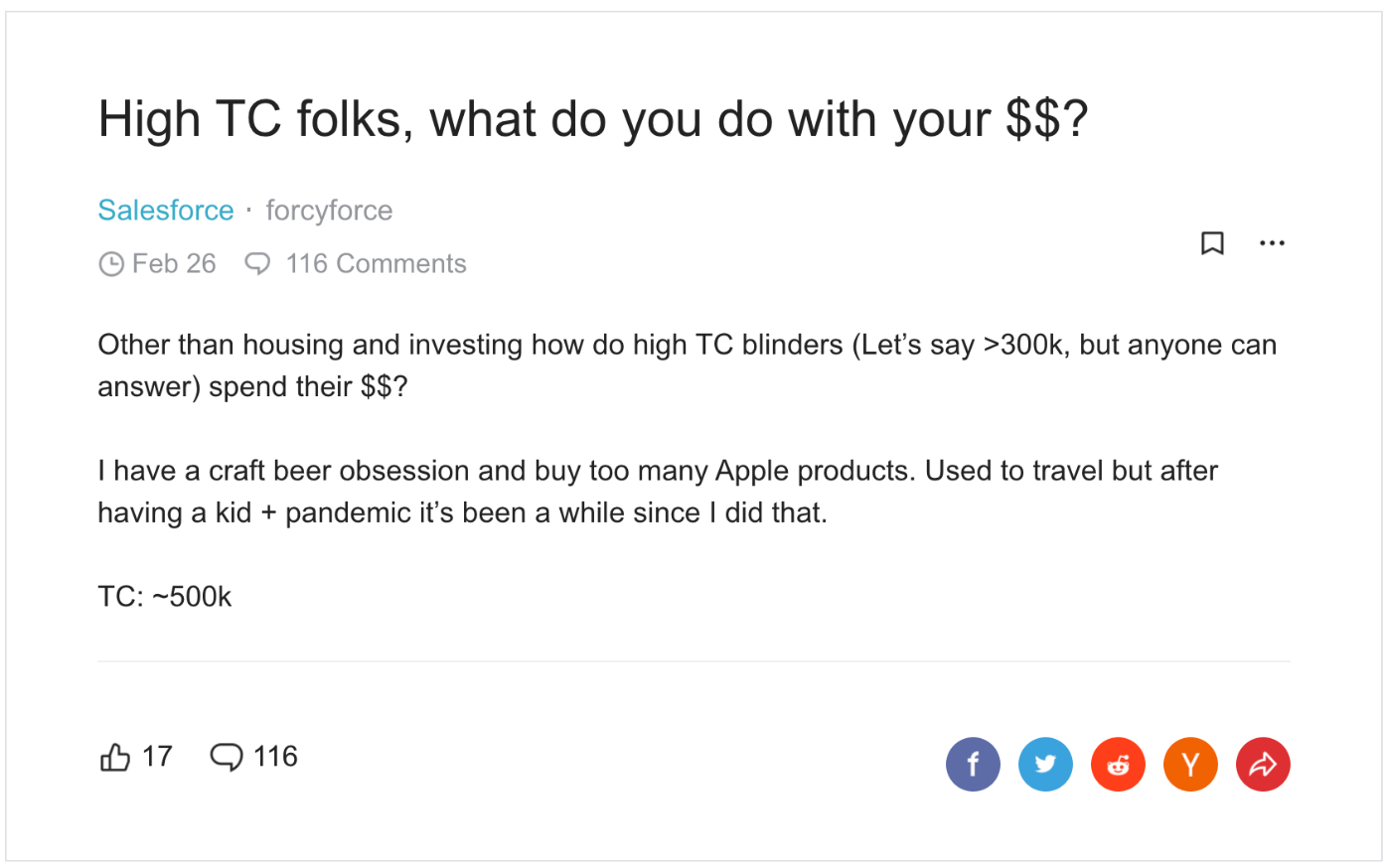

But on Blind, conversations provide a look at the mindset of people who have not bought into the myths. Arguably, they’ve made a worse trade—holding up money as the object of worship instead, finding little meaning at work beyond winning the compensation game. But winning the game seems to grant little real happiness for the champions. After all, beyond a certain income—that many tech workers surpass immediately—additional income follows the path of diminishing marginal returns. You just get to compare impressive net worths, ponder buying your own airplane, and experience having more money than you know what to do with.

In September 2021, a long-tenured employee shared their parting confession on Blind in a thread titled “Last day at Amazon after 11 years, no one cares”:

“... [I] feel like I don't matter. Yes I am moving to better TC and company, but I spent 11 years at this company. Launched so many things, did so much, but did not accrue any friendships. Spent a third of my life here and no one cares. No one cares enough to even have a call, to say all the best or anything.”

After over a decade at the company, they lament receiving no formal farewell or a goodbye celebration with colleagues. While some users extended their sympathies (“Congrats on moving on, sorry you were surrounded by jerks”), others placed the blame squarely on the leaving party (“Sorry that you’re going through this, but there’s definitely some learnings here if after 11 years no one is sad to see you go”). One faction seems assured something similar could not happen to them (“I left Amazon after 5 years as L5 and I glad I made a lot of friends who are still connected”), while others seem resigned to the idea that this was par for the course, a reality of modern work, and an occupational hazard of doing business (“No one except Bezos is gonna get remembered for Amazon.”)

Stories like this are not uncommon on Blind. One one hand, they illuminate why much of the “TC or GTFO” culture thrives on the app. Blind provides a window into why vague promises—culture, mission, objectives—mean comparatively little next to the promise of financial security and financial freedom that winning the game might afford. In companies with thousands, tens of thousands, or hundreds of thousands that optimize profit above all, it’s understandable why individuals make the same choice and advise others to do the same. But on the other hand, conversations on Blind demonstrate the cultural breakdown that can happen at companies where—despite stock grants—few feel a sense of true ownership. Despite the compensation and perks, the retention at many FAANG companies remains low. When people are always looking towards what’s next, there’s little incentive to contribute to fixing what’s broken.

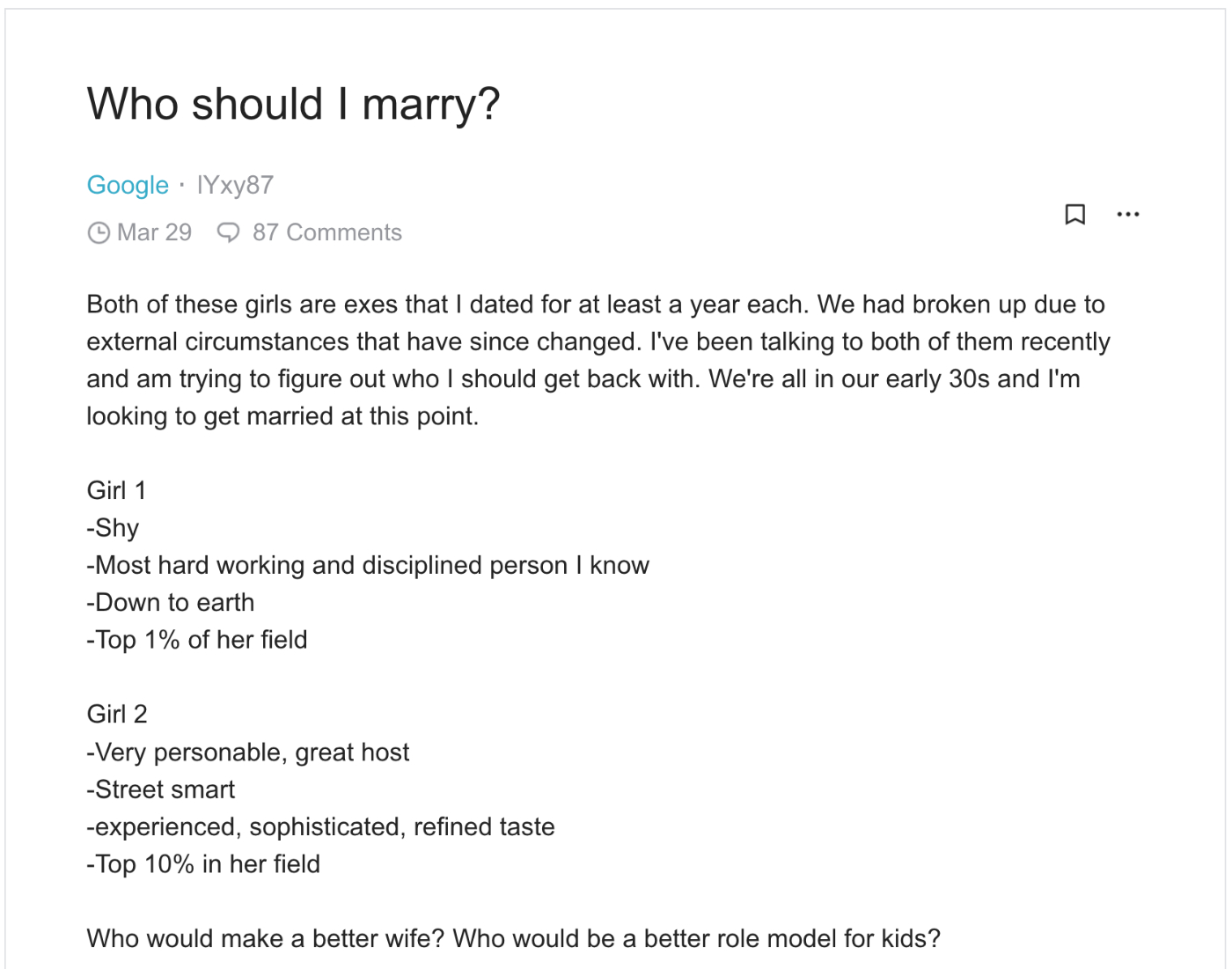

In corners across Blind you can see people attempting to opt out. But often, that means temporarily working even harder for an aim like FIRE (financial independence, retire early), which requires you to save most of your income with the hope of resigning from your tech job before 40 and living off the interest while focusing on passion projects. Alongside work, people try to find meaning in other areas of their life they discuss on Blind, like romantic relationships. But again, the culture of optimization and optionality only seems to have leaked into people’s personal lives. In one conversation, an engineer asks strangers to weigh in on whether he should marry girl 1 or 2, listing a few bullets under each one, in the same way people on the platform compare job offers.

With work taking up a significant portion of our lives, it’s worthwhile to find meaning through our careers, even when workplace cultures can make this challenging. But there’s little meaning to be found working at a company you feel is mostly fungible to the one you’re interviewing at to escape. If Blind is any indication, hopping from company to company chasing higher compensation, and spending a year or two at each one, is hardly a meaning-making pursuit. There’s little joy to be had in work that’s simply a means to an end, refreshing your company stock price or counting down until your stocks vest, eyes fixed on the revolving door.

Thank you to Rachel Jepsen for her invaluable editing of this piece. Additional thanks to Dan Shipper, Kate Lee, and Evan Armstrong for generously reading early drafts and providing thoughtful feedback.

Thanks for reading Cybernaut—an exploration of internet culture, from the idiosyncrasies of social media to the subcultures that exist in less frequented corners of the web. Subscribe for free to read articles on students caught in the Study Web, cashing in on Clubhouse, the blurred lines of parasocial relationships, online pseudonymity, and more.

A paid subscription gets you subscriber-only articles, access to the entire Every bundle of newsletters, and entry into our Discord community where we discuss topics ranging from the creator economy and crypto to writing and recipes.

Comments

Don't have an account? Sign up!